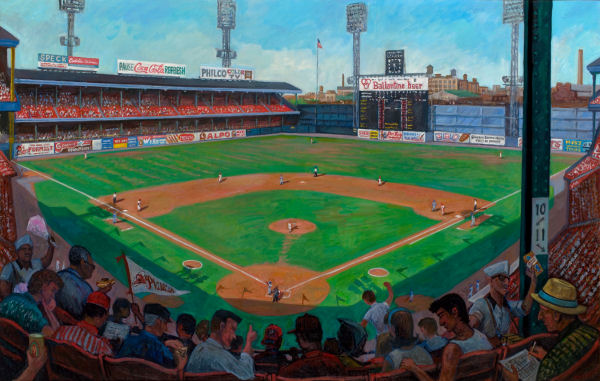

In 1964 I began to listen to Phillies’ games. I loved Bill Campbell’s home run calls. His voice and visits to Connie Mack stadium, the best of old hulks, gave me a boy’s green love of baseball. My father took me several times. We always sat on the third base side under the upper deck. My first time there I watched Dick Allen hit a triple off the Ballantine beer scoreboard in right center field, and on a later trip I saw him launch a home run onto the left field roof.

Charles Cushing’s painting of Connie Mack Stadium

I played hardball and softball and wiffle ball at the playground 100 yards down the alley from my parent’s home. The blank wall of an old brick elementary school rose 50 feet high in left field about 200 feet away from the batter’s box. Hitters shellacked that wall regularly. You learned to play the caroms off its angles. If you didn’t pull the ball, and you hit it on the sweet spot, that wonderful thunk-feel of contact would make your forearms feel as big as if you were Popeye. You watched the ball disappear into the leaves of the maples that lined the street in right field, and then waited for the crunch when it dropped onto someone’s car. The arc of the ball going up and up and gliding – that was beautiful, and similar in beauty to the lovely sense of poise I felt when I released a jump shot on the court tucked into a corner of the school’s recess yard.

I played hardball and softball and wiffle ball at the playground 100 yards down the alley from my parent’s home. The blank wall of an old brick elementary school rose 50 feet high in left field about 200 feet away from the batter’s box. Hitters shellacked that wall regularly. You learned to play the caroms off its angles. If you didn’t pull the ball, and you hit it on the sweet spot, that wonderful thunk-feel of contact would make your forearms feel as big as if you were Popeye. You watched the ball disappear into the leaves of the maples that lined the street in right field, and then waited for the crunch when it dropped onto someone’s car. The arc of the ball going up and up and gliding – that was beautiful, and similar in beauty to the lovely sense of poise I felt when I released a jump shot on the court tucked into a corner of the school’s recess yard.

1964 was the year of the Collapse. I had only a slim understanding of how the Collapse occurred. The human element of fatigue and questionable moves by the manager – these went right past me. I only saw something terrible happening in slow motion. Ten games lost, the pennant gone, no World Series? What? It felt like a terrible natural event – a flood, a long storm – and thus as if the fans, caught and powerless, could only stand and watch and sorrow.

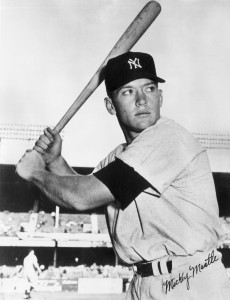

I became aware of Mickey Mantle in the 64’series against the Cardinals. The nuns would let us bring in transistor radios, and at 1:00 or so we would turn our bodies towards the center of the room and listen to the play-by-play man; we saw what happened in our collective imaginations.

Mantle’s body was broken by the point – his knee had been a mass of bone-on-bone-daily -pain for years, but he still hit three home runs. I don’t remember him though, but I still have the image of Bob Gibson, very tall, standing so straight and motionless on the mound, raptor-like in his focus, and then that big kick and full bore delivery as if his life wanted to follow the ball to the plate and freeze the bat in place with its intensity. I had never seen anyone like him.

Mantle’s body was broken by the point – his knee had been a mass of bone-on-bone-daily -pain for years, but he still hit three home runs. I don’t remember him though, but I still have the image of Bob Gibson, very tall, standing so straight and motionless on the mound, raptor-like in his focus, and then that big kick and full bore delivery as if his life wanted to follow the ball to the plate and freeze the bat in place with its intensity. I had never seen anyone like him.

Only after Mantle had retired, and I began to read baseball books did I begin to become aware of what I had missed. Thus Mickey Mantle by Jane Leavy.*

Leavy both loves and pities Mantle. This isn’t a muckraker’s book. There are plenty of stories here about his adulteries and drinking, but there are also stories about Mantle’s generosity to teammates, his capacity for playing in pain, his heroic clutch hits, his long home runs which entered legend as soon as they landed.

One of her underlying themes seems to be the eternal conflict between the gift of athletic talent and the wear of time and chance and temptation upon that talent. Unlike gods, Mantle (and Mays and DiMaggio and Schmidt and Carlton and…and….) are as brilliant as the sun only for a moment, and then the decline begins. But Mantle labored under an additional layer of myth. He had to carry the what-might-have-been if he had not destroyed his knee when his spikes caught in Yankee Stadium’s center field drain while chasing a fly ball in game 2 of the 1951 World Series. Before that injury Casey Stengel had said, “He has more speed than any slugger and more slug than any speedster – and nobody has ever had more of both of ‘em together. This kid ain’t logical. He’s too good (13).”* After that injury some thought he had lost a full step going from the box to first base. He seems to have lost the ability to move laterally. His swing was so powerful that, with the addition of his knee injury, Leavy speculates that the power and weakness of his body conspired to tear itself apart. He corkscrewed his tendons and ligaments. Is that not a fate only a jealous god could design?

The book goes years beyond Mantle’s retirement, but as with most great athletes, the shadow of his body in full motion and glory clouds every part of his later life.

It will be rare if you and I are remembered at all 100 years from now, but on one boyish and almost religious level, wouldn’t it be grand to be remembered for this:

Preston Peavy, a hitting coach for Peavy Baseball in Atlanta, speaking about Mantle:

“His proportions are classical, ideal. The length of his arms and his legs enabled him to implement a modern swing. He’s not particularly square; not particularly long in the torso; he wasn’t a fireplug. He was a truly gymnastically proportioned athlete. If you wanted to build a baseball player from scratch, Mickey Mantle was it. He was built for this (408).”*

Think of Mantle watching a white ball arcing higher and higher, heading out, over the roof, into the street, and he doesn’t even hear the crowd because he is so immersed in that sliver of time and space peculiar to his body’s action, and he has never felt more alive, ever. What would you trade from your life for one at-bat like that in front of 60,000 human beings who are all together wailing of their love for you?

Four wonderful books about baseball:

Willie’s Time by Charles Einstein

Why Time begins on Opening Day by Tom Boswell

Five Seasons by Roger Angell

The Boys of Summer by Roger Kahn

Hey! Whats with Pop taking you to ballgames? I never went…….. Did Fred and Annette also go along? What a nice memory. Wish I was invited……… ;(