After four years away from him and in spite of his actions, by the end he reclaims my sympathy. After four years of not reading or teaching this play, and of not listening to the voice of its lead, and in spite of Hamlet being a killer and guilty of acting so badly towards Ophelia, and of having lost his better nature for much of the play, I cannot turn on him.

He has more lines and words than anyone else in any of Shakespeare’s plays. He cannot stop speaking. His consciousness is monumental. Who besides those few closest and most intimate with us do we know as well? He tells us everything he knows as he comes to know it especially regarding his uncertainties — he initially doubts the identity of the Ghost; he cannot abide Ophelia or his mother; then he reconciles with his mother and erupts in violent grief upon learning of Ophelia’s death He cannot act; then he wipes out Polonius, Rosencrantz, Guildenstern and Claudius without a second thought. The only people he does not mock or condescend to in this play are Marcellus and Horatio; then in Act III he praises Horatio with such warmth and sincerity that we catch a glimpse at who he had been before the world fell upon him. He remains confounding.

He has more lines and words than anyone else in any of Shakespeare’s plays. He cannot stop speaking. His consciousness is monumental. Who besides those few closest and most intimate with us do we know as well? He tells us everything he knows as he comes to know it especially regarding his uncertainties — he initially doubts the identity of the Ghost; he cannot abide Ophelia or his mother; then he reconciles with his mother and erupts in violent grief upon learning of Ophelia’s death He cannot act; then he wipes out Polonius, Rosencrantz, Guildenstern and Claudius without a second thought. The only people he does not mock or condescend to in this play are Marcellus and Horatio; then in Act III he praises Horatio with such warmth and sincerity that we catch a glimpse at who he had been before the world fell upon him. He remains confounding.

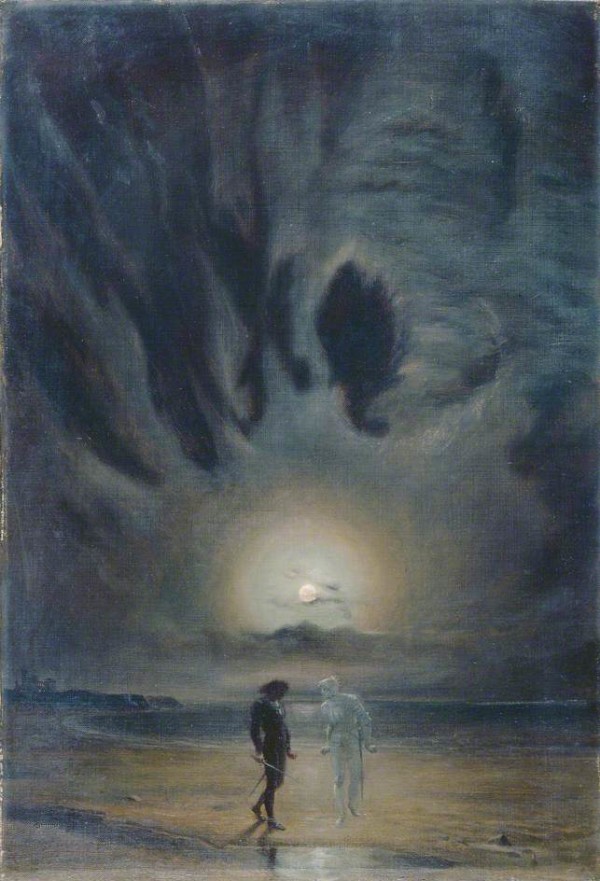

The Young Lord Hamlet by Philip Calderon, 1868

Ironically, it is Claudius who best describes him. When he says of Ophelia’s madness that her condition is “the poison of deep grief,” he understands her — by unknowing extension, he also characterizes Hamlet. Hamlet has been poisoned. Poison corrupts cells and either causes them to die, mutate or shut down. It operates at the molecular level. Drop by bead by morsel by trace, it breaks Hamlet. The poison begins its work before the action of the play even begins.

He learns of his father’s death in Wittenburg, hundreds of miles distant from Elsinore. He never has the chance to say goodbye. He arrives home and discovers he has lost everything — his birthright, his mother, Ophelia, his sense of place and purpose. The Court celebrates. He alone mourns. He must spend his days in proximity to the detested Claudius. Then the Ghost comes to him and delivers a terrible story and command. Like his father, Hamlet too “has been loosed out of Hell to speak of horrors.” Like his father, he cannot remain still. He cannot rest. Polonius remarks that sometimes he walks for “four hours” through the halls of Elsinore.

He trusts no one. Everything is jammed up and simmering inside. Combine overbearing grief, a suppressed rage, isolation and his uncertainty about his own lack of action and a man appears who has been driven out of normality. He says to Laertes “Yet I have in me something dangerous.” He has had something hot and dangerous in him from the very beginning of the play when he threatens Horatio and Marcellus. So when he does act, it comes all in a rush, the poison venting in acerbity and violence.

Ghost and Hamlet painting by Frederic James Shields, 1901

I get the sense that he must chant to himself “I must do something. I must do something.” I know what that voice sounds like, the one that says “Do Something. Do Something. Do Anything.” Then what a relief to be able to finally say “Now I could drink hot blood.” Finally, actions taken, it all goes wrong.

I recognize him. He sounds like a wild, bereaved friend speaking to me in a darkened room; a friend thrashing about trying desperately to figure out what has happened to him. Weirdly, his presence is so powerful, his reality so convincing, it is as if he believes in us, the readers under the lamp, the watchers in the darkness beyond his stage.

Hamlet Requiem Anatomical Speed Painting by Arkin Uren