August 11, 1965: Rioting broke out in Watts in Los Angeles after a confrontation between Los Angeles police and a black motorist being arrested for drunk driving. The looting and fires went on for six days. They resulted in 34 deaths, over 1000 injuries, and the destruction of over 2000 stores.*

August 18, 1965: Fifty two marines died in the battle of Van Tuong in Vietnam. The number of American causalities and the commitment of more and more troops to the war began to wound the country grievously.

August 26, 1965: Jonathan Daniels was only 26 when he stepped onto the porch of a store where he was shot-gunned at point blank range. He had moved in front of a young woman who seemed to be the target. He was white. Ruby Sales was black. He had traveled to Lowndes County in Alabama to help with voter registration. Not one black man or woman was registered to vote in the entire county. The shooter, Tom Coleman, then turned his gun on a Catholic priest and shot him. He lived. Coleman was acquitted by an all-white jury. Daniels was one of at least 34 who can be documented who died because they were directly involved in the Civil Rights movement beginning in 1965 — thirty six when Dr. King was assassinated in 1968.**

Martin Luther King visited Watts and was insulted by both the white mayor, Sam Yorty and by the police chief. He made little headway with crowds of young black men and women in Watts itself where the awful slogan “Burn Baby, Burn” had already achieved an archetypal status – more cities would burn.

June, 1966: In Gainesville, Mississippi Stokely Carmichael and King, linked arm in arm and marching to Jackson, the State capitol, disagreed publically about the use of “Black Power” as a new exhortation in place of the word “Freedom.” King worried that the slogan “isolates us, confuses our allies and gives whites who are ashamed of their bigotry an excuse to justify it.” ***

Their exchange: “I mean,” Carmichael replied, “that the only way that black people in Mississippi will create an attitude where they will not be shot down like pigs, where they will not be shot down like dogs, is when they get the power where they constitute a majority in counties to institute justice.” “I feel, however,” King interjected, “that while believing firmly that power is necessary, that it would be difficult for me to use the phrase black power because of the connotative meaning that it has for many people.” Carmichael walked alongside, hands clasped behind his back with beguiling pleasantry (487).”

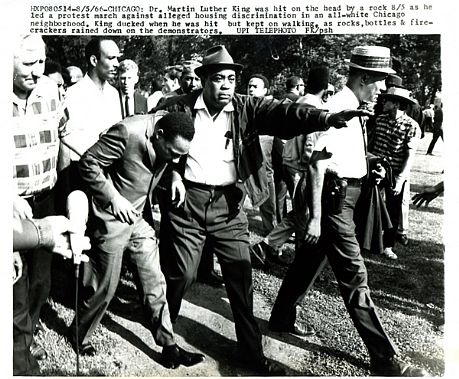

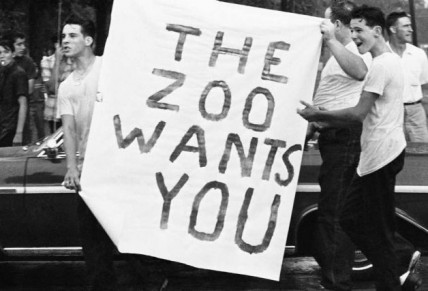

Against the advice of some of his aides, Dr. King moved his campaign for racial justice north to Chicago where the conditions of racism were much more complex and less easily defined than in Jim Crow Alabama and Mississippi. He met enormous official and street resistance and was struck down by a rock as he marched. Over two days, between four and five thousand men, women and teenagers threw bricks, knives, bottles, stones and cherry bombs at police and marchers alike; at one point they chanted “Burn them like Jews,” and one held a sign that read “The only way to end n****** is to exterminate.” His campaign ended with an agreement from the Mayor to increase pressure for open housing.

The FBI under J. Edgar Hoover, whose personal hostility to Dr. King was unrelenting, continued its campaign of wiretapping and vicious anonymous persecution (the wiretapping had initially been put in place by attorney general Robert F. Kennedy). Dr. King’s ability to lead was being steadily diminished by the implacable opposition of southern politicians, by the expanding war in Vietnam and its demands on the nation’s blood, treasure and attention, by the intractability of racial hostility, by the Movement’s splintering, by his own weariness, by tactical and strategic uncertainties, and perhaps, inevitability, by entropy itself – how can any one voice or body hope to stave off the growth of chaos or the loss of directed energy? He had been the center of the Movement, this American storm, since 1955.

In reading Branch’s book and in doing the research for this essay, I began to wonder if our present discord and the fracturing of a political consensus on anything did not begin in the years 1964 to 1966. The center was breaking apart, and no one could hold it together — President Johnson withdrew, Vietnam having wrecked his health and his Presidency, Robert Kennedy and Dr. King were murdered, and men like Nixon and Reagan exploited the fracturing and invoked the ethos of the tribe and the backlash of white fear and resentment.

In January of 1968, an “exhausted” King spoke to his SCLC staff: “Riots just don’t pay off,” said King. He pronounced them an objective failure beyond morals or faith. “For if we say that power is the ability to effect change, or the ability to achieve purpose,” he said, “then it is not powerful to engage in an act that does not do that–no matter how loud you are, and no matter how much you burn.” Likewise, he exhorted the staff to combat the “romantic illusion” of guerrilla warfare in the style of Che Guevara. No “black” version of the Cuban revolution could succeed without widespread political sympathy, he asserted, and only a handful of the black minority itself favored insurrection. King extolled the discipline of civil disobedience instead, which he defined not as a right but a personal homage to untapped democratic energy. The staff must “bring to bear all of the power of nonviolence on the economic problem,” he urged, even though nothing in the Constitution promised a roof or a meal. “I say all of these things because I want us to know the hardness of the task,” King concluded, breaking off with his most basic plea: “We must not be intimidated by those who are laughing at nonviolence now.” ***

In *** At Canaan’s Edge, Taylor Branch concludes his trilogy of the Civil Rights Movement. Reading it, you know what is coming. It is akin to reading Hamlet of King Lear for the first time or much worse, hearing the story of Lincoln’s murder after you had come to understand what he had accomplished during the Civil War. You know the ending before you begin, and thus you read on with mounting sorrow and horror as the inevitable deaths approach, as Dr. King’s death approaches.

History authenticates our losses; it makes them as hard and heavy as steel, but it also defies the law of time where everything is loss – mountain chains erode, continents shift, seas rise, stars extinguish, friends die suddenly. If only temporarily, it saves something. Taylor Branch (and others) saved this story of the Civil Rights Movement and of Dr. King. It would not be difficult to argue that all they protected was the sense of his terrible loss, and the implacable decay of the Movement’s promise, but I would argue for another perspective – that the preservation of these stories of astonishing courage and moral beauty can serve us now and always.

The bodies of Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman

The bodies of Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman

For example, at the first commemoration of the lynchings of Movement volunteers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Shwerner in Philadelphia, Mississippi in August of 1965 “Dr. King addressed participants amid jeers from white bystanders. He said, “I want them to know that we are not afraid. If they kill three of us, they will have to kill all of us. I am not afraid of any man, whether he is in Michigan or Mississippi, whether he is in Birmingham or Boston.” As the group began the return march, the white bystanders attacked with stones, bottles, clubs, fists, and shouts. The police held them back until some of the marchers began to fight back. That night, white marauders drove through African-American neighborhoods spraying homes with gunfire.”

***  Dr. King in Memphis just before his assassination

Dr. King in Memphis just before his assassination

Someone has done a count somewhere of how many times Dr. King literally walked into the inferno of racial hatred and abuse, of how many times he offered his body as a sacrifice — I know that as recorded in the three books of Branch’s trilogy, it must number in the hundreds. Again, in Philadelphia, in 1965: “I am not going to allow anybody to pull me so low as to use the very methods that perpetuated evil throughout our civilization. I’m sick and tired of violence . . . . I’m tired of evil. I’m not going to use violence no matter who says it! (489).” ***

He never lost faith in non-violence.

Dr. King was assassinated by one more failure with a gun, James Earl Ray, in Memphis on April 4, 1968. # King had come to do what he could to help garbage men who had been on strike over awful working conditions. He was 39 years old. It is so easy to forget how young he was when he died.

* Watts