Often, loving poetry feels like a useless pursuit in this most mercenary and utilitarian era. The Republic is darkening and poetry might feel like a luxury and an affectation, an absurdity to speak of, as if it is a frill, a personal gratification only, but poetry has become a necessary part of my life, as pleasurable as that first sip of coffee. It helps me tamp down my daily rage and sorrow when I open the Times and see what has come to pass while I slept.

Often, loving poetry feels like a useless pursuit in this most mercenary and utilitarian era. The Republic is darkening and poetry might feel like a luxury and an affectation, an absurdity to speak of, as if it is a frill, a personal gratification only, but poetry has become a necessary part of my life, as pleasurable as that first sip of coffee. It helps me tamp down my daily rage and sorrow when I open the Times and see what has come to pass while I slept.

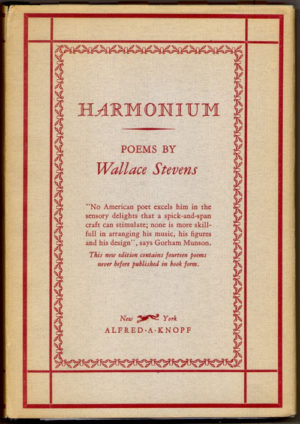

I read at least one poem and usually more than one each day. Their precision in the rendering of images, their combination of feeling and idea becoming a kind of normal transcendence and their description of the beauties and travails of commonplace mystery — all three of these qualities have taken hold of my imagination. And sometimes, everything comes together in a wonderful bang as it did for me recently when, finally, Wallace Stevens’ poem “Sunday Morning” gave itself up to me suddenly after more readings than I can remember.

A lounging woman on a late Sunday morning, still in her nightgown, sits in the sun, drinks coffee, eats an orange and looks at the image of a bright green cockatoo on the rug at her feet and thus begins to dream both of birds in warm fields and flying to roost at last light and also of “the holy hush of ancient sacrifice”, of “that old catastrophe” in “silent Palestine/dominion of the blood and sepulchre.” Stevens conjures a whole theology in her dream.

On this day his lyrics appeared iridescent, engraved as if in an old movie where the camera might linger upon a page of a book and a sentence grow bold and black for the audience’s eye — this kind of awakening, this surge of comprehension, the jolt of caffeine in the blood:

On this day his lyrics appeared iridescent, engraved as if in an old movie where the camera might linger upon a page of a book and a sentence grow bold and black for the audience’s eye — this kind of awakening, this surge of comprehension, the jolt of caffeine in the blood:

“What is divinity if it can come/Only in silent shadows and dreams?” and

“But when the birds are gone, and their warm fields/return no more, where, then, is paradise?” and

“There is not any haunt of prophecy,/ … that has endured/as April’s green endures….” and

“Death is the mother of beauty….”

She arrives at a conclusion in the final seven lines of the poem that are among the most beautiful I know. I will leave that conclusion to you and thus encourage you to read this poem and that last stanza and perhaps it will open for you more readily than it did for me.

In Ten Windows: How Great Poems Transform the World, Jane Hirshfield points out that “We write or read good poems because we need them…. In dark times, separation, isolation, and immobility cannot help; strength and will alone cannot help. What restores the capacity for humanness is the realignment that comes from finding ourselves simply, decently, moved” (182; 254).

Poetry is the full human in me, a kin to my breathing, a force field lodged seamlessly under my skin. If we look and think, we wonder. If we wonder, we try to place those words in an order that reveals the world to us and us to others. When we read poetry, we see that many too carry the pulse beneath their skins, that they too are moved and fight night terrors and love inarticulately, that they too are full of emotions and insights that they struggle to express. We learn that others have seen visions out there, and that we are not mad. We become a part of a larger, unmet community. We grow less alone. We are ‘decently moved” and perhaps restored to an equilibrium we are in peril of losing.