I had written material for teaching — lesson plans and reports and speeches and other similar kinds of forms and records, but I began writing for another purpose in earnest in January of 2011, a few months before I retired. I knew that teaching had released many things in the uncertain, timid boy I had been that I had never felt before, and two of them were a need to both connect with others and make real my own experience. So I began to write as a rescue operation of sorts. What do I know that I want to preserve?

In about 5 months I wrote 20,000 words in an attempt to ‘make real’ everything I had learned about teaching. I wanted to finish it by June so that I could publish it on a web site I had begun to design with the help of a former student (the site would not have been done without her advice and skill).

I wrote every day in whatever time I could find between retirement preparation, the last semester whirlwind of lesson planning and the usual avalanche of student essays. I surprised myself in this respect: I found that writing this piece was cathartic. I was making it an unknown audience. In publishing it on-line, I would give up all control over who would read it. I could make no assumptions about their awareness of arcane, ‘insider’ knowledge of the occupation. Therefore, I had to make it absolutely truthful in recollection, argument, content and tone. Its clarity had to be crystal. Each day I fell into it the way one falls into a pool, suddenly and completely.

In setting myself to such a comparatively long project, I discovered the immersive joy of the act itself. Writing is not just the physical act of sitting and typing out one’s conception of something. It is also the murmuration of thoughts and memories and comparisons and individual words and sudden sentences and realizations and lightning shots of inspiration and phrases said aloud while walking and driving and stopping the dogs while I fumbled in my pocket for a pen and tablet to jot it down so I could let my mind race on. It is the whirring, diving, quivering feel of thinking, the envelope of consciousness itself in its full, purring life. It is bloody joyful.

Writing becomes all of these — a purpose, a task, a pursuit of craft, a grappling with what makes something true, a commitment to the refinement of language, a commitment to clarity, an unspoken promise to not betray an audience you do not know nor to betray your own integrity.

Five or six years ago, when I began to read poetry as seriously as I had always read fiction (and had now begun to write it too), I cut out and set upon my desk two sentences from the poet Philip Levine that made more sense to me about the experience of writing than anything I had read previously: “There comes a time when you realize that everything is a dream and only those things preserved in writing have the possibility of being real,” and “I think poetry will save nothing from oblivion, but I keep writing about the ordinary because for me it’s the home of the extraordinary, the only home.”

I began working as a teacher at 22, and I was callow and ingenuous, but even then I had a skimming awareness of the felt reality of death that only became more present and insistent in my 30’s. After attending so many funerals of students, and since the death of my first wife when I was 43, it has become that force that takes up the space right next to me. I think about it every day. Thus, I write, to try to prove myself real and to leave behind for a brief time a record of what I saw and felt and shaped. I think that if I am writing, I am still vital, still looking around corners. What I have written will function as a simulacrum of my voice, and the voice is the first part of ourselves to disappear from the memory of others. Of course, I know what will happen, that anything I have written will eventually be cast into fire or buried in a landfill or wind up in the peculiar afterlife of internet erasures, but during the act of writing, that doesn’t matter. What matters is that while writing, I can feel ‘it’ moving through me, this voltage, humming.

I started writing poetry because it allows me to write about subjects in ways that an essay cannot manage as well. For whatever reason, I can push language more in a poem, compress sentences into phrases, phrases into words, and thus give it a more powerful gravity.

Poetry for me is also the only form that will manage the ‘ghost drifts’ within me and in others.

Our enclosure of consciousness takes notice of this flood of images and sounds, and emotions of every kind, and bodily awareness and thoughts. All of this, wisps of impressions and the more sustained kind of thinking, is going on simultaneously. Poetry better captures these ‘ghost drifts’ than anything else I can do, in myself and in what my intuition and experience tells me takes place in the more mysterious lives of those I meet who bear these same ‘ghost drifts’. In this respect, among others, Levine is absolutely right when he says that the ordinary is the home of the extraordinary.

I should say that I attempt to do these things. With every book of poems, I learn more about how to write. I learn more about how to frame them, cut them, choose them, speak them aloud, discard those that do not work, polish those that do. It is the work itself that I love.

Maybe that is the other reason I persist. Everything I write is flawed. There is no end to becoming a better writer. There is no end to struggling to improve. Thus, writing becomes an affirmative dialectic: each morning I sit down to write, each time I pull out a pen and hastily scribble a few words at a stoplight, each time I repeat a line that came to me while walking, each time I complete a poem or essay, I must move to the next step. Writing says I may not stop. I must complete the process. I must begin, finish, begin again. Writing says there is no completion until the end.

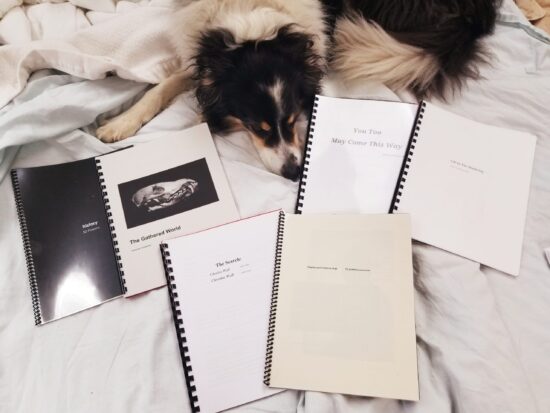

I will not call myself a writer. I have no publisher. The only books (a malleable term) I’ve ‘published’, I’ve paid for myself at FedEx. I mail a few of those off to friends and family who are kind enough not to look at me pityingly in my presence. No one has paid me one dime for one word. So, I cannot lay claim to the noun, only the verb. I write every day and will do so until the end, and so should you dear reader, for your stories are more valuable than gold coins. Your stories are what you leave that lasts the longest.