In eighth grade I wrote a book. During some recesses I sat on the side of the yard and watched the boys run, one bold son occasionally breaking free to scamper up to a knot of girls and shout and cause them to giggle. I watched the girls jump rope and huddle in groups and look at the boys. I watched the nuns in their shawls looking at us, tall creatures with the added height of their serre-tete and cap, blue monoliths who I saw occasionally laugh out here, released for the moment from the curious gaze of their enormous classes.

I wrote down what I saw, and what I imagined would be glorious things to come for those boys in high school. The book was a biography of the class, two or three sentences describing each boy, but none of the girls. It never occurred to me to describe any girl. That would have been like trying to imagine what sister world might exist on the other side of the Sun. Unthinkable. Unknowable.

I remember the poorly drawn cover of the book, a misshapen body and head in blue ink, but not one word of even one sentence. I do not remember if I showed it to anyone.

However, I somehow knew that one could see a lot by being quiet and looking and remembering.

The only girl with whom I had spent time was a neighbor who owned a giant German Shepherd. We sometimes walked together after school. That ended when I asked her to go to a basketball game with me in 7th grade, a multi-faceted disaster that included me spilling a sticky cup of warm Pepsi on an old woman with blue hair while trying to climb the bleachers to deliver it to Theresa who then tried with every fiber of her body language to affirm that I was an alien, an oddball boy in a paisley long sleeved shirt, probably a killer, but oh nonnonno no one she knew. We left at halftime of the varsity game. We had not spoken another word to each other after the poor old woman had squealed and gasped and stumped away. At her door, I reached out for her hand. I have no idea what was in my head. She pulled it back and in one motion raised it in an open palmed, stiff-armed salute and said, “Heil Mike.”

I am not making this up.

I was often the one who watched, the boy on the edge of groups, the one who talked too much when he got excited or when he wanted to be noticed and then fell back into a corner. I read books and watched confident classmates move through our jumbled lives as if they could walk through anything solid — the opinions of others, the scrutiny of priests and parents, the stew of our own hormones, growth spurts, shifting alliances, the mess we became in trying to find a groove in life that felt right. Nothing seemed to bother them, at least from what I could see.

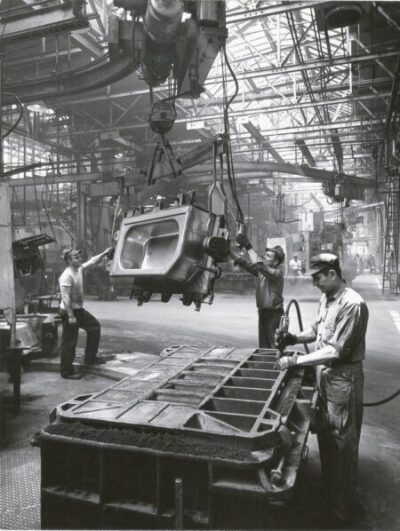

Until college, when a dissolute first semester brought me to within hailing distance of expulsion, I was an indifferent student, mostly bored, an autodidact to my core, always reading, sharp-eyed of others, figuring out the world through each fall, fight, book, bike journey, bump-and-go interaction with friends, basketball game, jammed together night time thrill ride, ineradicable moment of fear, sublime moment of joy. With the exception of a handful of classes and teachers* both in high school and college, I received more of an education through my jobs as a janitor, in factories, a supermarket, a meat packing plant and for one summer working on widening roads with the PA Highway Department and with a cluster of the filthiest beast-men I have ever known.

When I worked at a restaurant, I watched the owners of the restaurant, a husband and wife, scream at each other on the steps above the dining rooms about his drinking and her missteps with the menu. Invisible, I collected dishes, cleared tables, cleaned up messes, learned Pennsylvania Dutch curse words in the kitchen and how to carry trays piled with plates and glassware so heavy they made my arms tremble. I found out that waitresses and busboys and line cooks shared an accord — we were the ones who served and disappeared, like bodies that could shift from spirit to corporeal at the flick of an eye, the waggle of a finger. We had to watch, were paid to stare and thus we saw the Sunday families with wailing children and tired parents, the Saturday evening older couples who did not speak to each other, the sloppy men at the tiny bar calling out in too loud voices for ‘another one’, the first dates so steeped in a demure, smiling reticence that one wanted to drop a tray to give them something to talk about. We saw breakups in their shuddering, tense stand-off’s and stiff-bodied leave taking as if they had been transformed into glass.

During high school, I never thought about working, never questioned why I was doing it. My parents did not push me to do so. It was a matter of ‘I have a body that moves. What will I do with it?’ I visited other planets — that’s what I did while at work, worlds outside the gravitational pull of father and mother and school, places where I arrived without a past. I was ‘the new kid’, the ‘who’s that?’, the ‘c’mere, I’ll show you how to do it’ boy. I discovered that losing one’s history is exhilarating. Nothing drags behind you when you enter a room. Not a nickname, not a public embarrassment, not a reputation. You arrive cleanly scrubbed, a fresh take for others’ eyes.

I learned how to deal with bosses, what made a good one — fairness, directness, kindness. The good ones took the time to teach you how to wrap a head of lettuce, speak to a customer, wipe down a blackboard to wash away streaks, deal with strangers. How to clean the bathroom of a college classroom building, how to pack a truck, pick up loads using your knees, avoid useless arguments with big mouth’s, cut 50 pounds of sheet metal accurately, trim 10 pound blocks of ham and how to pace yourself over 8 or 10 hours on your feet.

Work showed me that most people know things you do not know and genuinely like to share their hard-won knowledge. All you need do is ask. I figured out how to ask.

I was lucky. I had more good bosses than bad, but I learned from them too — how to slide past the bad ones as if one were an actor performing diligence and putting on the bearing of an adult. How to listen and all the while drift among the stars. I saw that their contempt for their workers derived from their characters. Bad bosses were almost always awful human beings except when they were merely pathetic and in over their heads.

I am still trying to piece together the puzzle of high school, a mere 4 years that has acquired an uneven importance in my American life. Can it possibly carry as much weight in other cultures? I wonder if I haven’t been trying to fit those 4 years into their proper, diminished place for 50 years.

In high school I became well-educated both in the stratifications of cruelty, how the pack draws together to nip and tear at one of its own, but also in the joy of being an animal running with other pups, all of us pups, and laughing until we drew up breathless. I found out I did not like being told what to believe or what to do but also how eagerly I conformed so as to have a spot in the affections of others, and so I grew into camouflage like those strange pictures of artists who have painted themselves the same pattern as their backgrounds and thus disappear. In high school, this is how one hides, I think. This is how one endures in the company of others where one craves to belong.

In high school I became well-educated both in the stratifications of cruelty, how the pack draws together to nip and tear at one of its own, but also in the joy of being an animal running with other pups, all of us pups, and laughing until we drew up breathless. I found out I did not like being told what to believe or what to do but also how eagerly I conformed so as to have a spot in the affections of others, and so I grew into camouflage like those strange pictures of artists who have painted themselves the same pattern as their backgrounds and thus disappear. In high school, this is how one hides, I think. This is how one endures in the company of others where one craves to belong.

Until late in my senior year, girls swirled in circles around me, figures flying in the tremendous winds of the hurricane. I turned in circles in the eye of the storm, and when friends stepped into those winds and formed relationships, I swear I thought I had seen mystical events. “My God, they’re flying with them,” I thought, “and holding hands and kissing and yet they remain as idiotic as I am. How can this be?”

When my turn came, finally, to step into the wonderful storm, well, language cannot encompass the screeching, monkey-swooping disbelief and wonder of it. With girls, one can be both fundamental simpleton and second-string god simultaneously.

I kept watching, the advantage a high school beta had over alphas. We had no status to protect. Camouflage has many virtues. I took in how too many classrooms that operated as domains of a petty, oppressive power, airless and anesthetizing. When they could not dominate us, we tore them apart.

I watched how even the constrained power of a teacher can become intoxicating, capricious and cruel. I saw how easy it was in those classrooms to give up, to let go of effort and drift. I did it myself. However, with 3 or 4 teachers, I witnessed how those same classrooms and students boiled into life, into an eagerness to learn that was supernatural in its production of joy and community, its contrast so stark with the dead zones of much of the day.

When it came to my turn to teach, I remembered all of this.

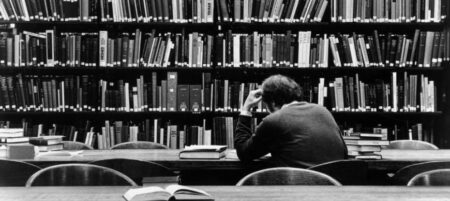

But all through grammar* school, high school, and every day in college, I never stopped reading histories, classic novels by the score, works on astronomy and geology, books on animals, on adventure, on travel, plays, studies in anthropology, philosophy, geography and politics, magazines, the Times. I took up residence in the college library. In desperation, I learned to organize myself, and I finally trained my ability to concentrate on my classes even if their drudging, unvaried dullness made my brain numb. I kept my head clear. After that first semester, I lived austerely … mostly. I had figured out there was a real life after college.

But all through grammar* school, high school, and every day in college, I never stopped reading histories, classic novels by the score, works on astronomy and geology, books on animals, on adventure, on travel, plays, studies in anthropology, philosophy, geography and politics, magazines, the Times. I took up residence in the college library. In desperation, I learned to organize myself, and I finally trained my ability to concentrate on my classes even if their drudging, unvaried dullness made my brain numb. I kept my head clear. After that first semester, I lived austerely … mostly. I had figured out there was a real life after college.

No more to be a fireman or a Marine or a solemn philosopher, these others I had never met before decided that I was going to teach actual children English. What fools. What saviors.

*Counting to myself just now, including grad school, I could name 8 or 9 out of 80 or closer to 90 classes and teachers that I can say were transformative.

*Catholic Grammar schools were organized by grades 1 through 8 in one building, all classrooms self-contained. No kindergarten. When I stumbled into my 1st grade classroom, I was 5 years old.