I do not miss it, but I dream of it. Never of the new building, only the old school built on a former hay field, the place of dingy hallways and massive windows and trees in the courtyard. Sometimes I awaken in a start knowing I have not prepared for the day’s lessons. What does it say that one dreams often of rooms and corridors that no longer exist?

Ten years out feels like my third life, the decades in front of kids still real, undreamlike, but far removed from a routine that no longer includes the Sunday night tightening of the gut, a form of anticipation of performing 25 shows over five days. That routine no longer includes stacks upon stacks of essays to grade, Department duties, the preparation of lessons I worried were never clear enough, creative enough, worth the time of the kids who could not leave my room for 50 minutes.

When I retired, it was as if I had left a pressurized chamber where I had lived for 36 years and had reappeared on a planet with the gravity of the Moon. For months, weightlessness was the norm. My days were free and possessed this strange quality of both release and hollowness. Traditional gravity returned, of course. One’s approaching mortality carries its own dimensions of pressure. And, I could not be still. Within nine months I was back to work. The years since have dissolved to this point, ten years since I retired, that good round number that suggests enough time has passed to make one more judgment about what I learned.

The central tenet I hold to has not changed: the relationship between high school teacher and student and teacher and individual class is intensely personal, direct, and visceral in the same way that actors forge connections to audiences. Except that teaching is a performance where the actor also bears a measure of responsibility for the well being of each member of the audience. The teacher is an actor who must know the names of those who take a seat. He or she must strive to be aware of their sadnesses, potential, circles of friends, the quality of their lives away from school, their aspirations, some part of their history, their passions, their uncertainties. The caution in all of this that rises to the level of an ethical absolute is that this relationship may never become intimate in any sense of that word. Teachers must forever look out from a distance all the while they attempt to bridge that distance. The resulting equilibrium is the paradox at the core of the job. It is the essential tension of the work.

Second, in order to acquire authority, the teacher must give up power. A high school classroom can become a tiny empire where even its tiny power can become a temptation to indulge in spiteful actions and sarcasm, a small and wretched form of cruelty. Kids will fight back against this, and they can become the masters of asymmetric warfare — rumors, pranks, the noises that come from anywhere but always nowhere that can disrupt a class, insolence up to a finely calibrated line, an air of disrespect that is corrosive in its long term effects.

To be successful, a teacher requires authority, not power. Authority emerges from trust and respect. It comes from a teacher’s willingness to admit mistakes, even failure. To apologize, to negotiate, to shut up and listen, to thank, to protect, to work hard, to sacrifice time and perhaps even well being. Students must grant a teacher authority. They will chip away at power.

Third, the classroom should be an intensely sympathetic crucible, alive, demanding and forgiving, a realm of surprises, itself a dialectic based upon clarity that also promises swerves and reversals of direction. It is where the mystery of voices operating in both concert and respectful opposition create a society that lasts mere months but whose affirmative effects might endure for a lifetime.

Finally, the teacher’s voice is at the core of this mystery, the voice that must persuade those who may not leave the room that they should imagine their freedom in the possibility of the many lives they might choose to live, lives brought into focus by literature, theorems, equations, hypotheses, other languages, lives that emerge on the field, court and stage, through the complexities of science and history, and for me, the most important of all, through their own writing. If young men and women are taught to write well, then they can think clearly and do so in their own distinctive voice. The teacher’s voice not only must give way to students’ voices, his or her voice must encourage that transmission. Teaching only works at its best when the students who leave a classroom have been purposely strengthened to discover the best parts of their own minds and hearts. I think writing does this more so than any other skill.

I still teach of course, with scant idea as to whether anyone listens. The habit of pointing things out or explaining does not go away, but one risks the possibility of becoming one of those old men who drift about grunting out opinions or stories, never noticing the glaze of paralysis descending over the faces and bodies of those they’ve trapped. So, I only do it in writing where with one click a reader can turn away and mutter, “Sheesh, what a windbag.” In the company of others, unless they want conversation, I keep respectfully taciturn.

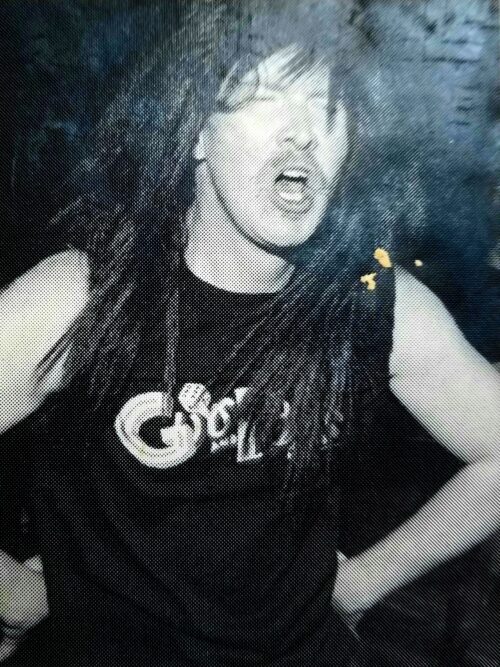

It was rock ‘n roll too. Early 90’s. A faculty show.

It was rock ‘n roll too. Early 90’s. A faculty show.

Now, a little stunned, I think of all those years, one after the other, and of new faces appearing before me in the regular beat of each summer rolling into fall, but I remained in one building*, a fixture (although that almost changed**), my hair growing longer with a few years of a terrible mustache and a hideous goatee thrown in, then reverting to a Marine cut, then growing longer again. Growing broader across the chest. Marrying. Grieving, Marrying again. Coaching. Being fired from coaching. Taking my turns on negotiations’ teams. Attending meetings, more meetings, more meetings, more meetings. Attending the funerals of children, more funerals than I can count. Taking stats on the sideline for the football team for 13 straight seasons and thus seeing up close the remarkable ease of great athletes and given leave to witness a series of masterclasses in what superb coaching looks like. Winding down into exhaustion each May and June. Yet, coming back fresh each September, my energy renewed, my normal pace walking in the hallways midway to a sprint, anxious to be better than I had been the year before.

I do not believe in fate, and choice and chance are so screwily intertwined I challenge anyone to declare that one person alone is the pure architect of his or her life. I fell into teaching, afraid, a fool, a diffident boy, but I fell into a profession of the generous and forgiving who saw something in me I did not know was there, and they gave me time to grow. My students provided me with the perennial freshness of youth and the innocence to make me want to do right by them. I tried my best not to let anyone down. I worked hard. I had such fun. I loved all of it.

*with one year in the Middle School, that a story of true love and for another time.

**I spent part of the summer of 1978 flying into Idaho, Washington and Oregon interviewing for teaching positions. I received an offer to teach at Boise High School the day before classes were to begin at Owen J.