I do not know who taught me to work hard. Neither of my parents, who all in all were pretty laissez faire about child rearing by the time they got to me. Maybe I just looked at them in perpetual motion and took the hint — there is only one speed, forward, go. Or maybe like my brother and sisters, we carried the DNA of Depression experiences inside us, received from some Jungian collective memory and taken to heart. All 4 of us hustled. When I arrived at student teaching, I had memorized this part of the equation: hard work solves most problems. Although I didn’t know it before I walked into my first classroom, my other advantage was my voice, my father’s baritone finally arriving when I needed it most.

I had yet to stand before a class and teach a lesson, face so many strange, younger eyes, handle a question, assert authority, shape a 45 minute community, overcome a problem child or a class wild as barbarians who yearn for a blood sacrifice.

If you have never taught an audience who may not leave their confinement, one that contains any number of children who do not want to be there at all, who think you look like some dopey Ichabod Crane motherfucker, and perhaps go after you teeth and fang because it relieves them of boredom or gives them points in the high school hierarchy or maybe because they react to fear in prey the same way a wolf pack will — chase ‘em down, grab hold, rip ‘em up — well, can you imagine it now?

If you have never taught an audience who may not leave their confinement, one that contains any number of children who do not want to be there at all, who think you look like some dopey Ichabod Crane motherfucker, and perhaps go after you teeth and fang because it relieves them of boredom or gives them points in the high school hierarchy or maybe because they react to fear in prey the same way a wolf pack will — chase ‘em down, grab hold, rip ‘em up — well, can you imagine it now?

Yet, I wasn’t afraid. That absence of fear had nothing to do with courage or control. It had to do with focus. The job now lay before me — 16 weeks of student teaching. First in a middle school, then a high school. Then, graduation. Then a position and pay and my own place and the beginning of ‘real life’. I thought purely in terms of that straight line. I would get through it class by class, day by day. Regroup. Adapt. Move on. I had the imagination of a snow plow that could occasionally downshift and make turns … and smile. Friendly Mike, your happy teacher who will clear your roads with a happy toot of his horn and happily run you over if you play a game of chicken with him. Toot, toot.

I was lucky in the pick of the draw with my cooperating teacher, Mrs. Anna Schafer, a maternal, patient woman in her 60’s, my junior high mentor, Chuck Tannery of Springhouse Junior High in the Lehigh Valley and William Shaw, my high school mentor at Kutztown HS. Both men were very good teachers and decent human beings. Both had the confidence to look past my mistakes, my rookie debacles, and think that maybe I would one day be worthy.

I knew enough to keep my mouth shut. Veteran teachers do not care to listen to yappy 21 year old’s offer opinions on the best way to do anything. Rule #1: Do not be a pain-in-the-ass. Rule #2: Pay attention.

At lunch, I followed conversations, noticed which teachers commanded respect and which did not, and tried to figure out the why’s of that distinction. I also asked for advice, lots of advice. On how to create good composition assignments, answer a question whose answer I did not know, seat a class, know where to stand, how to hand tests back, decide how to dress, how to transition from one topic to another, how to handle that little prick Carson who keeps joke-farting, what to do to help with poor soul Faith who looks so sad every day.

I taught my first lesson, an introduction to The Great Gatsby, to Mr. Tannery’s best class, lovely ninth graders, who smiled and laughed and responded to my questions, and with Mrs. Schafer seated in the back who blushed again and again at how well I was doing, how happy the class was to be with me, and after they had left, chattering and joyful, I walked back to Mrs. Schafer, lovely, kind, happy Mrs. Schafer, still pink with such a blush, and she turned her head and pointed down, and I looked and my fly was open all the way, a part of my dark blue tucked-in-shirt peeping about like a wee animal come out to say hello.

Mr. Tannery laughed. Other teachers laughed. I found out that teachers have a wicked sense of the absurd and that they forgive occasional, rookie idiocy. I recovered. When I admitted to the blunder to the class the next day and laughed about it with them, I also discovered that kids can forgive if one is humble with them, human with them, a person, not a persona.

Romeo was right. Just like that I fell in love. No other word is adequate to explain what I felt in the classroom whether I was lecturing, doing question and answer or working with kids individually. All of it was … pure, as if a new dimension to my life had been added in one crackling moment of contact. Nothing had ever made me happier.

My voice came into its own. I figured out how its temper and tone, its layers of pitch, inflection and volume could change the mood of a class in a moment — settle them, move them, overpower them, gentle them, cause them to laugh or go so quiet in anticipation that every sound became magnified in importance. I got the hang of how silence, the withholding of my voice and the abrupt stillness of my body, could create openings for learning I had never foreseen.

This too happened: I could tell a story, my father’s only talent for performance, and I sometimes heard them coming out of my mouth making use of his same rhythm and pauses.

Most importantly, I recognized that I liked people. That sounds strange. It’s not. How many teachers have you known who do not like human beings? Now think about that number you just calculated.

I liked teenage people especially — their idealism, goofiness, ability to set fires in an instant, their uncertainties and quests, their willingness to take chances, the exquisite seismograph of their sensitivities, their limitless capacity for laughter, their powerful bullshit detectors, their innocence even at their most cynical.

My experience continued in high school with juniors and seniors and that produced its own rough moments — hard cases and wanna-be tough guys, lessons that blew up, lessons that died, classes that went so quiet and cadaverous that I wondered if I needed to make resuscitation a skill. I doubted, fought back, returned to my apartment exhausted, fell onto my bed and slept for an hour, got up, ate food for fuel, walked to my building to do my custodial job, came back, sat down at my desk and began again.

Midway through all this, with only weeks left before graduation, I began applying to school districts in Delaware, New Jersey, Maryland and all over south eastern Pennsylvania, a labor intensive process of letter writing, filling out dozens of applications by hand, making sure my application package to be sent out from college was up to date, and arranging for transcripts to be mailed. Then one called each district twice a week and wrote thank you notes and reminder notes and all of this while teaching and planning and cleaning 4 classrooms, hallways and toilets 5 nights a week. I was rail thin, smoking heavily, eating badly and running on the inexhaustible energy of rude, coarse, invulnerable youth.

I worked with a friend whose father was employed by a district I had never heard of, surprising, considering it was only one county over. He said there were 3 openings in English. Why not? One more application made no difference. I applied to Owen J Roberts.

I began interviews in June, a strange round robin of meeting groups of strange looking men who had emerged from some dress rehearsal of a bad rock ‘n roll movie in 60’s knitwear allied with 70’s long sideburns. Armed with my own newly acquired array of polyester shirts, polyester ties, polyester trousers, clunky black shoes and a short haircut, I was ushered into my interviews looking 12 years of age. No, 11. Most twelve years old’s had more muscle mass than I did.

I began interviews in June, a strange round robin of meeting groups of strange looking men who had emerged from some dress rehearsal of a bad rock ‘n roll movie in 60’s knitwear allied with 70’s long sideburns. Armed with my own newly acquired array of polyester shirts, polyester ties, polyester trousers, clunky black shoes and a short haircut, I was ushered into my interviews looking 12 years of age. No, 11. Most twelve years old’s had more muscle mass than I did.

I remember the two interviews with Owen J the best. Number one was with three men in a middle school classroom, one of whom was the high school principal. Number two took place in an office jammed with men, 8, 9 , more, crammed into corners, squeezed onto a couch, standing, the Superintendent being one, a big man wearing an open collar shirt with enormous lapels and iridescent black razor-cut hair. I sat at one end of this mass on a chair separated from all other humans and was bombarded by questions from all angles, some being asked as I finished the last sentence of the previous answer. I remember my head swiveling. For all I remember of what I said, I might have answered in fake Portuguese and told them the story of how I lost my hump.

When it was over and one of the men walked me out, I was dazed, but he was happy and told me I had done well.

In the last week of June of 1975 I received three phone calls. I had a job offer in Prince George’s County in Maryland teaching a group of only 90 students in an experimental curriculum designed for at-risk youth, at Freedom High School in Bethlehem teaching tenth graders, and at Owen J teaching grades 9 through 12 in mixed enrollment quarter courses. I would have my own room.

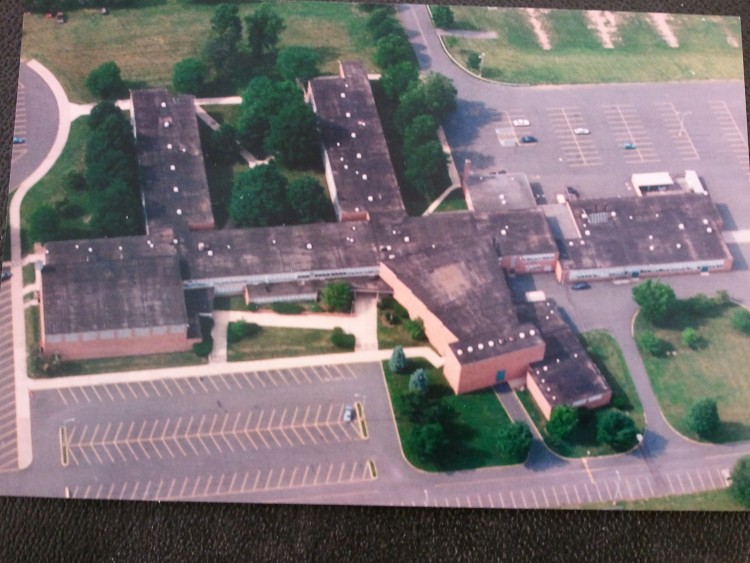

The High School sat atop a hill that overlooked northern Chester County — all green, empty farmland. The classrooms had giant windows and big trees grew between its wings. I would have my own room, my own, and I would be teaching all kinds of students many, many subjects.

I made the choice quickly. My parents were overjoyed — their prodigal son, this once-a-freak become a freak no more had a job that would always be there — there would always be children, of course there would be — and a job with benefits, praise be, the boy had a job with benefits.