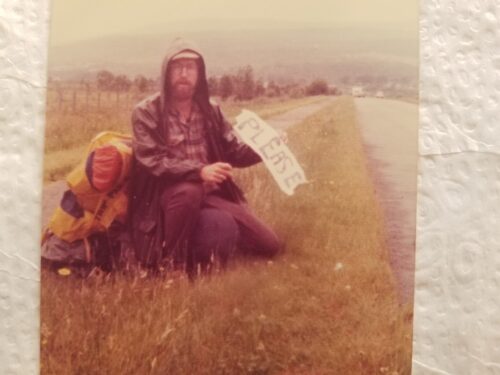

In the middle of July on the Isle of Skye and on the Outer Hebrides, it rained for nine straight days. Sidewinding rain, deluge rain, misty rain, soaking rain, and when it occasionally cleared and the heat rose, midges appeared … and kleggs, a creature I was convinced I had imagined until I read the letters again. I like my spelling better, but they are Clegs, a Highland horsefly that cuts the skin rather than pierce it. They fell upon us on the road. We ran to escape them, humping our packs and signs like demented peddlers escaping angry villagers. We swung our arms about our heads. We cursed. We smoked. The midges came on us in swarms like some silly Biblical curse, the clegs descended, and in the rain, who wants to stop to pick up two large wet men carrying  dripping packs and dancing like dervishes? We took to performing little 5 second vignettes when a car approached — we took turns running toward the other and leaping into each other’s arms and then flashing our hitchhiker sign. We got lots of laughs but few rides. We walked. We cursed. We laughed. We were tired. I have so little memory of the landscape or of our rides. Skye was a through point. We did not stop until Uig where we boarded a ferry for Tarbert. In northern Scotland, we had entered old Viking country.

dripping packs and dancing like dervishes? We took to performing little 5 second vignettes when a car approached — we took turns running toward the other and leaping into each other’s arms and then flashing our hitchhiker sign. We got lots of laughs but few rides. We walked. We cursed. We laughed. We were tired. I have so little memory of the landscape or of our rides. Skye was a through point. We did not stop until Uig where we boarded a ferry for Tarbert. In northern Scotland, we had entered old Viking country.

In Skye with the Clegs.

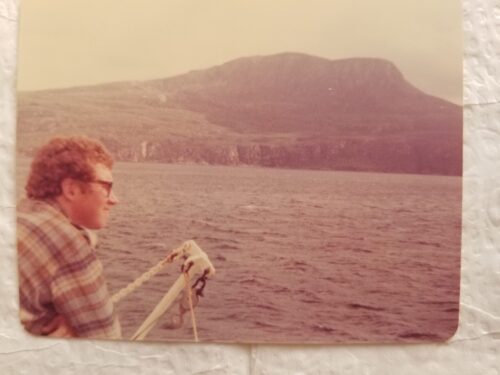

From the water, Tarbert looked savage, a place of scattered, low houses thrown upon granite headlands under a low, gray sky. It was cold. The rain went on.

From the water, Tarbert looked savage, a place of scattered, low houses thrown upon granite headlands under a low, gray sky. It was cold. The rain went on.

Coming into Tarbert.

We had booked a few days in a B and B miles within the island where Mrs. Maclane took one look at us and ushered us into her tiny sitting room, our packs left dripping on the stone floor of the hall. She gave us her good chairs before a peat fire and brought us tea and bread and butter and treated us as a mother would treat her weary, wet children. We slept in a second floor room in a bed piled with red tartan blankets where a window looked out upon a landscape empty of trees, a place of rock and sky. I remember finally getting warm sitting up in that bed, drinking tea, reading, looking out the window when the sun occasionally broke through, a little in awe of how I had come to this place. No one on the planet knew where we were.

There’s always a pub nearby. This one sat alone in a hollow a mile or so from the B and B along a gravel one lane track, no other building within sight, one small whitewashed building with men pissing against an outside wall, and inside, men the size of defensive lineman wearing Wellingtons and bits and pieces of yellow fishing clothing, all of them blond, most of them happily buzzed, every one welcoming of Americans come to their little place, Americans with stories about America, about New York, about the always wild west.

I do not remember the name of the big man who bought us drinks and came out to tower over me at the pissing wall. I can see his hard, sharp face and his hair so blond as to fade into the light and the solid size of him. Tony was 100 yards away and heading over the crest of the hill and back to our lodging. This Viking stood close to me, swaying a bit and said he needed a favor. Yet, I did not sense any aggression coming off him. There was nothing predatory about him. I finished and smiled and listened.

“Please, when you go back to America,” he said leaning in, “Please mail me a pony. I want to ride a pony and be like John Wayne in Oklahoma and go riding over the grand plains.” And he raised his hands in such a delicate gesture as if he was holding reins, and he bent a little at the knees and lurched up and down as if riding. I told him I would mail him a pony. I asked him what color he would like. He would like a paint. Yes, I said. I took his address scrawled on a stained napkin. I waved goodbye to him, this happy man already seeing himself astride a great pony carrying him away over the heath.

We ferried again from Harris to Ullapool in the Highlands, hitched to Inverness and for the only time on the trip rented a car for a few days and made our way to Loch Ness where we took out a boat and went out upon the waters hoping for Nessie and rowing so happily in the Sun.

We kept hitchhiking north after that to Lossiemouth on the North Sea where RAF fighters smashed the air above us and our attempt at camping on a spit of land overlooking the ocean was blown apart by gale force winds that threatened to roll us into the sea. From there to Edinburgh on a ride with an off duty policeman. A Jehovah’s Witness convention had taken every room in the city. We made ready to sleep on narrow, wooden benches at the train station until Tony suggested we try asking the police where we might find a room. The desk sergeant looked us up and down and offered to let us sleep in the drunk tank that night. Why not? We were led down corridors through steel doors to one more that opened into a long empty cell with cement floors that sloped to a gutter. The policeman wished us a good night and locked us in. We slept well, dry and warm and safe as houses in spite of the periodic screaming of one man from an adjoining cell.

This feels as if I am writing down hill, events jamming together, but it might have felt like that at the time too.

We split up after Edinburgh, Tony heading to Leeds and me taking a feverish-sore-throat-worndown bus ride to Sussex and an old friend from my exchange student days. Martin lived in a 16th century Tudor home with the lowest ceilings of any place I have ever stayed, but he was a gem to take me in and feed me and bring me back to health.

Tony and I met in Trafalgar Square and for a few days in London saw shows and concerts and stayed with his Aunt in the basement of an expensive town home on posh Victoria Road. Unlike Tony’s mother, his mother’s sister had avoided the war altogether and eventually married a genuine war hero who also would have been a prime target for assassination by the IRA.

His Aunt employed a live-in Filipino maid. On a night off, she returned to the house later than she was allowed*. She did not want to be discovered returning after her ‘curfew’ by Tony’s Aunt so she came knocking at our basement door very late.

When the knocking commenced, we awoke, panicky, and for about 10 seconds whispered about the IRA come to take out the husband. Perhaps it finally occurred to us that the IRA would not have softly knocked at the door and whispered in a familiar voice if they intended mayhem. We opened the door, the maid came in, flustered, half-crying, terrified she would be fired.

We knew that his Aunt was married to a powerful man who had responsibility for Northern Ireland. Neither of us knew just how powerful or we would have been more frightened. The IRA had murdered the British Ambassador in July and in March had exploded a bomb in London. Our uneasiness was not misplaced.

We flew home a day or so later. I needed to hustle to ready myself for year two of teaching and Tony returned to Portland, OR where he had been a member of the Jesuit Volunteer Corps for the previous two years.

I’ve struggled to place this trip in perspective. I had traveled out of the country twice before — once to study at a small college in the midlands of the UK and once on a mission trip to fix a water pipeline in the countryside beyond Ciudad Victoria in Mexico. Both times, I had been a member of a larger group who had very specific purposes. On this trip, the two of us floated about the islands improvising, changing destinations, free from any obligation. We were explorers traveling with Traveler’s Checks and American passports and in our white man skins — a whole set of privileges and protections that are easy to see now, but then, we were impossibly young and free in a way no longer practicable. We carried no phones. We moved by strangers’ cars and by ferry and bus and foot. We moved through empty places and through war zones and in great cities. No device tracked us. We found caches of letters awaiting us in Edinburgh at the American Express Office, our only awareness of events occurring with family and friends. When we could find it, we read The International Herald Tribune. For two months we watched almost no television and did not listen to radio.

I learned how to meet and talk with and especially listen to strangers of every kind during rides, in pubs, in quiet moments in B and B sitting rooms. I became more confident about simply moving through the world on my own, and more important than anything else, I became acutely aware of the infinite range in ways of living a life. Writing this now, one moment comes to mind as an example.

We were somewhere in Ireland, somewhere along the coast. It might have been Galway but I can’t be sure. We had a brief conversation with a middle aged woman. We may have been asking directions.

She was carrying a laundry basket. She had dark hair. It was a sunny day. She smiled often and laughed. She said she had “12 bonny children” and laughed, both delighted with herself and surprised. I remember thinking that “bonny” was an adjective we should hear in Scotland. I remember thinking of my own mother. I remember thinking about my own self-absorbed few years. Here she was, a person I had never thought of, living such a rich life all that time. What a marvelous world, I thought, what a marvelous world.

*At the time neither of us understood the kind of abject servitude under which such “guest workers” were (and are) employed.