Nate Rice loves his work but since his work entails frequently visiting some of the wildest places on the planet, he has some very bad days. He has “raced up mountains in West Africa just ahead of the loggers “to collect bird specimens whose extinction is guaranteed. Some of these species never fly over “one hundred yards away from where they were born. They can’t just move.” He has seen the after effects of Chinese capitalism, locust capitalism, in the mountains of northern Vietnam where “some poor border guard is paid a couple of dollars and 100,000 acres disappears.” This is what disappears looks like: “They clear cut all the trees, strip the top soil and then mine what’s left for gravel. Then they leave.”

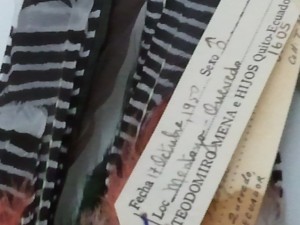

Woodpeckers from all over the world

Woodpeckers from all over the world

Nate Rice is the Collection Manager for Ornithology at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. He manages one of the great collections of bird specimens in the world. Two thirds of the Academy’s footprint is storage space for their vast assemblies of all kinds of life, 20 million all told of shells, insects, animals, plants and birds — two hundred thousand preserved birds, some of them reaching back to 1750. He collects 1000 new specimens a year without leaving the Academy, “salvage birds”, those who have crashed into windows or fallen prey to cats, but he has also journeyed to Paraguay, Guyana, Vietnam, and Mexico on collection expeditions. He takes a sampling of birds, never those whose populations are threatened. He is very clear about what he means by “takes” – he shoots them or takes them from mist nets. They are “sacrifices for the collection.” Born and raised in northern Wisconsin, he was a hunter and fisherman before an ornithologist; he does not use euphemisms when he speaks. He is “worried about the planet” but also committed to his scientific work, his life’s devotion. He studies the dead so as to preserve the living.

My wife, mother-in-law, Alma, and father-in-law Earle, all three

birders who keep life lists, watched as Nate rolled open 100 feet of steel and baked enamel cabinets on compactor rails. For an hour and a half he removed shelf after shelf and spoke of the birds that lay in them, their skins “like parchment paper”, stuffed with sterile cotton now instead of horsehair, arranged in rows, each with an identification tag attached to its leg. Until 1920 they had been preserved with arsenic. He is tested each year for exposure.

Bird feathers capture chemicals extant in the environment, especially the common elements of carbon and nitrogen, and thus are perfect vehicles for figuring out what was present in the air and soil and water of Guatemala in 1915 when the Turquoise Brown MotMot was taken or how the pre-industrial Everglades differ from our time as held within the bodies of birds killed and preserved by Audubon.

We saw Golden Headed Manakins and Birds of Paradise from Australia with three foot long tail feathers, Fiji Frogmouths and Nightjars collected in 1839. We saw a broad tailed hawk shot and stuffed by Kit Carson on his 1845 expedition to the American West. We saw all of the Type Specimens of Australia. Type Specimens are taxonomic firsts – they are the standard by which all other members of the species are evaluated.

We saw the Cuban Bee Hummingbird, at 3 grams, the smallest bird in the world. It had been collected by James Bond, an ornithologist and a friend of Ian Fleming who took his name for his spy. We gazed upon the wealth of the world as measured by more complete standards, those of beauty and bio-diversity.

We saw birds collected by Alfred Lord Russell, the co-discoverer of Natural Selection and Evolution who lost the work of years of collecting in the Amazon in 1828 when his ship sank on its return voyage to England; he spent weeks on a raft awaiting death.

We saw how the range of extinction has taken its toll in samples of the Ivory Billed Woodpeckers and the Imperial Woodpecker of Mexico, the Carolina Parakeet and the Passenger Pigeon, the last one “probably the most numerous bird on the planet; it made its home in the billion or so acres of primary forest that once covered North America east of the Rocky Mountains. Their flocks, a mile wide and up to 300 miles long, were so dense that they darkened the sky for hours and days as the flock passed overhead. Population estimates from the 19th century ranged from 1 billion to close to 4 billion individuals. Total populations may have reached 5 billion individuals and comprised up to 40% of the total number of birds in North America (Schorger 1995). This may be the only species for which the exact time of extinction is known.”* They were wiped out by habitat loss and market hunters.

Nate rides “an emotional roller-coaster” on a daily basis. He is in love with birds and with wilderness, with science and its elemental questions, but increasingly on his field trips he races against the brutal acquisitiveness of implacable economic forces to save whispers of what once existed in a river valley or on an equatorial mountaintop. On foot he literally sprints to keep an hour or two ahead of man-made extinction. In person his enthusiasm for life, for study, for teaching, for the Academy’s priceless array of thousands of birds is irresistible, but I wonder if on his worst nights he doesn’t have nightmare visions of what he has seen and of what may be coming.

My cell phone sits beside me. I am typing this on a lab top. Both contain rare earth elements such as europium, praseodymium, samarium. Parts of the Congo have been obliterated in their mining. Americans sanction the amputation of whole mountaintops in West Virginia to get at coal seams and thus annihilate eco-systems that have existed since the last ice age. I drive a car, and I burn oil to heat my home, and thus I am guilty of creating an enormous carbon footprint. The Chinese bulldozer driver smashing through a rain forest ultimately is one small moving part of our interconnected economic systems. I live inside that web. It makes no sense to descend into guilt or breast beating over this. One might as well shake his fist at the sun. So I follow the logic and draw this conclusion: we are the locust species, and intelligence is a curse, an evolutionary suicide formula wired into our genetic code. How else to describe any trait that methodically reduces the natural world to tens of millions of acres of lifeless, pitted slop?

But that line of thought is ultimately nihilistic and misanthropic; to reject hope is to accede to despair. Science has the capacity to change how we as a species see and understand the physical world. Our intercession is necessary for enough of it to be saved so as to promise its expansion later. Nate Rice does his part to alert the larger world to what is happening. He walks into marvelous places and takes from them that which will serve life. Now, he memorializes them. Perhaps, soon, those memorials will have a better chance to also continue as a part of vibrant cycles of life and death.

I’m sorry. That last paragraph feels false. It is my attempt to sound a note of optimism, to send forth a desperate shot of faith. I know how individual heroes can bend the curve of history toward goodness, but how does any one person bend the curve of a global system based upon industrial and technological power, a system that must expand to remain viable? There is no such organism as steady-state capitalism. It must grow. As it grows, it eats rivers and rain forests, prairies, temperate forests, the tundra, fish and fowl, animal and plant life. I do not fear the sound of that organism’s machinery. I fear the absolute silence it leaves behind, the stillness of a sublime natural world emptied of all that is separate from our voracity.

*Chipperwoods Bird Observatory