Martin Luther King Jr. threw himself out of his upstairs bedroom window because he thought his younger brother had killed his grandmother when he flew into her while riding the staircase bannister.* He was five years old. He refused to rise until he had been assured and reassured that she was alive. He repeated this when he was twelve when she died of a heart attack.

Martin Luther King Jr. threw himself out of his upstairs bedroom window because he thought his younger brother had killed his grandmother when he flew into her while riding the staircase bannister.* He was five years old. He refused to rise until he had been assured and reassured that she was alive. He repeated this when he was twelve when she died of a heart attack.

In light of what he became, I don’t know what to make of those leaps; I’m not sure what they might signify about his psyche, if anything at all of importance. The weirdness of these acts startles though. I’ve tried to remember actions I took out of fear when I was a child or such actions as related by others. I’ve heard plenty of stories describe crazy risk taking, a few involving panicky children hopping in their parent’s cars and driving away, and one about a seven year old climbing to the top of a tree to escape being blamed for something and remaining there for hours while ignoring the pleas and orders of family, police and fire department members to descend, but not one about blind jumps out of second story windows.

Nothing I have read indicates that he sought death as an adult. Instead, witness after witness speaks of his stability and calm in the middle of conflict.

This fact matters. He survived those falls. History changed because of his survival.

I want to know how we come to our place in adult life. What circumstances and choices make us into who we become? I especially want to know how men and women of note arrived at their settled lives, at that spot where we can recognize them for their exceptional nature. The larger questions concern all our lives. Where does individual initiative intersect with chance? When do we begin to believe in the myth we make of our lives, the narrative we build for ourselves that tells of our endurance or heroism or kindness or toughness or wisdom or grace or steadiness or two dozen other virtues that we believe may form the core of our existence?

I cannot see myself clearly enough to figure out such answers for my life — too many blind spots; plus, the narcissism of such a personal meditation is repellent. I’ve tried to answer these questions about my father. I’ve thought about them in regards to Lincoln, Melville, Alfred Kazin, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, T.E. Lawrence, Churchill, Meriwether Lewis, but right now, for many reasons, Martin Luther King has the most urgency for me. He was at the center of the great internal American drama of the 20th century, the push to finally end many of the long political and social effects of slavery. His oratory, his bravery and his early death by assassin have sometimes rendered him unapproachable, his humanity reduced to myth through the lens of monumental history. How does one see through the myth? How does one begin to answer questions provoked by his lines of will intersecting with lines of historical force? How to see through the rubble of those collisions? More incredibly, how to explain the absence of collisions but instead the melding together of those lines as if in doing so they smoothly created something utterly unlike us, a bronze statue on a grand boulevard instead of a frail body and the blood that was spilled?

I only know that we have to try to break the statue and look at the mold, at the steel superstructure, at the components of bronze, at the copper and tin before they are mixed and set. The human being may then flicker into view. Did you know that Dr. King played musical chairs with club members from the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church? See that in your mind’s eye — as the music stops, Dr. King slipping past an upright woman from the choir and skipping into a seat, laughing at his harmless impudence. The bronze is still there? Strip the Doctor from his name. Strip Martin Luther from his name. Imagine him only as M.L., an unknown young man who at 16 years of age quits a job “because the foreman insisted on calling him nigger (63).”* Look at the verb “insisted”. That strongly implies that ML asked that the foreman not describe him using that awful word — at 16, a young black man in Alabama in 1946 resists this word with a white man in a position of power. In the same summer of 1946, six black war veterans were lynched in the South in a three week period. When he was sixteen, ML was stepping toward manhood in a realm of serious danger.

When he was twenty six, he was leading the Montgomery Bus Boycott. He was in charge of morally and physically resisting a power structure that wanted to crush him and the black population of Montgomery, Alabama and continue their subjugation. He was the point man responsible for organizing upwards of twenty thousand rides a day (146)* to keep the boycott functioning. He persevered in his leadership for over a year, and when they finally won, when the buses were to be fully desegregated, his photo appeared on the cover of Time magazine and his name and face entered the national and international lexicon.

These lines intersected in Montgomery:

Rosa Parks refused to leave her seat on a Montgomery bus and was subsequently arrested. She made her choice. The NAACP made their choice; they believed she could stand up to scrutiny. Her action was the trigger for all the events that followed.

Rosa Parks refused to leave her seat on a Montgomery bus and was subsequently arrested. She made her choice. The NAACP made their choice; they believed she could stand up to scrutiny. Her action was the trigger for all the events that followed.

ML King was the pastor of a church and a powerful orator, the son of a pastor, a man steeped in both learning and the tradition of the black church as the most prestigious of institutions in the community. He had seen that father confront “a white patrolman who had pulled him over and snapped, ‘Boy, show me your license.” [His father answered,] ‘Do you see this child here? He pointed at M.L. ‘That’s a boy there. I’m a man. I’m Reverend King (10).’”**

He had embraced the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr at the Crozier Theological Seminary, a man who wrote that “evil is a permanent part of human life” and therefore that good men and women must “combine love, politics, spiritualism and realism” in a quest for justice. He wrote that we cannot avoid or hide from “the corruptions of the world” and that evil must be confronted.

ML King had the example of Vernon Johns, another Dexter pastor who in the deepest era of Jim Crow had dared to file rape charges against six white policeman on behalf of a member of his congregation, and who had posted this sermon title on his message board outside the church, one block away from the Alabama State Capitol building: It’s Safe To Murder Negroes In Montgomery. The KKK burned a cross on the church lawn, but he gave the sermon.

ML King had the example of Vernon Johns, another Dexter pastor who in the deepest era of Jim Crow had dared to file rape charges against six white policeman on behalf of a member of his congregation, and who had posted this sermon title on his message board outside the church, one block away from the Alabama State Capitol building: It’s Safe To Murder Negroes In Montgomery. The KKK burned a cross on the church lawn, but he gave the sermon.

1956 at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church — how young he is….

ML King is elected to lead the boycott because he was the only one who could unite all the black pastors of Montgomery in the effort; he was not the most forceful possibility. E.D Nixon “taunted” the ministers with these kinds of sentences: “You ministers have lived off these wash-women for the last hundred years and ain’t never done nothing for them. … If we’re going to be mens, now’s the time to be mens.” ML King arrived at the end of this “scolding”, and said, “Brother Nixon, I’m not a coward. I don’t want anybody to call me a coward.” He said that “all the leaders should act openly, under their own names (136-137).”* He was elected without objection.

I have to believe that as a young man he sensed something opening up, an opportunity that would not come again, the possibility of taking action in a way that would lift him up to the eyes of many, many others. Maybe he felt a sense of destiny about him. Maybe his young man’s ambition captured him.

This intersecting line is more aptly described as a fuse – his sermon on December 1, 1955 at the Holt Street Church to a crowd of anywhere from five to fifteen thousand men and women who had come to rally to begin the boycott. He usually “required fifteen hours to prepare an ordinary sermon (138).”* He had about ½ hour to prepare his words for this, his most important time in the pulpit.

Branch spends over 4 suspenseful pages describing this sermon and draws this conclusion: “In the few short minutes of his first political address, a power of communion emerged from him that would speak inexorably to strangers who would both love him and revile him, like all prophets (142).”*

Another line, a terrifying one, a line like a rope. He is arrested. The police drive away from the downtown jail. He admitted that “panic [had] seized him. …. The farther they went, past strange neighborhoods toward the country, the more King gave in to visions of nooses and lynch mobs (160).”* He had to confront the fear that he was being taken to be murdered, that he was about to meet the fate of thousands of other black men who had been lynched. What layers of empathy must that ride have awakened in him and what profound lines of connection to others who had been subject to arrest and similar fears.

Another line, a terrifying one, a line like a rope. He is arrested. The police drive away from the downtown jail. He admitted that “panic [had] seized him. …. The farther they went, past strange neighborhoods toward the country, the more King gave in to visions of nooses and lynch mobs (160).”* He had to confront the fear that he was being taken to be murdered, that he was about to meet the fate of thousands of other black men who had been lynched. What layers of empathy must that ride have awakened in him and what profound lines of connection to others who had been subject to arrest and similar fears.

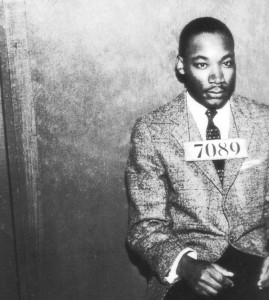

MLK’s Mug Shot from his first arrest.

Finally there is this moment, the line drawn with the deepest shade, the heaviest indentation – under the pressure of death threats and of being the figure most responsible for keeping the morale of the boycott participants at a sustained pitch, under the pressure of keeping teams of workers unified, under the psychological stress produced by lack of sleep and by emotional and physical exhaustion, he almost broke.

He leaves a meeting in his living room and walks into his empty kitchen. He “buried his face in his hands at the kitchen table. He admitted to himself that he was afraid, that he had nothing left, that the people would falter if they looked to him for strength. …. His doubts spilled out as a prayer, ending, ‘I’ve come to the point where I can’t face it alone.’ As he spoke these words the fears suddenly began to melt away. He became intensely aware of what he called ‘an inner voice’ telling him to do what he thought was right. …. It was for King the first transcendent religious experience of his life 162).”*

When I read this, I thought of Lincoln, a man swimming in daily grief and unimaginable pressure, someone not given to church going, who began to speak of Providence, who said in his second inaugural address that “The Almighty has His own purposes.” Lincoln found his way to what has been described by scholars as a mystical understanding of his role as President. In this moment I think we see King beginning to sense the presence of the same kind of grace and comfort and motivation.

I think we share this with men and women who have done great and good deeds — at some point all of us have fallen into despair and in that state have revealed our frailities. Rarely do our strengths connect us but instead our struggles show us best, grappling with all the uncertainties of our actions and of those converging lines that often both lift us up and crack us open. I think we connect with such men and women and with most others by how we try to rise up from our anguish, by how we fight to go on. Martin Luther King is most approachable in his moments of humility, in his stubborn refusal to give in to his own fears, and in his readiness to pay a price for doing good. That is where our lines might intersect with his.

*Unless otherwise noted, the facts I have presented about MLK come from Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-1963 by Taylor Branch

**Let the Trumpet Sound: The Life of Martin Luther King, Jr. by Stephen Oates

Both books can be ordered/purchased from the Wellington Square Book Shop. Help save independent book stores.