I think it’s been there since my Aunt Elsie read to me from the Book of the Martyrs. I have had an interest in the history, actions and personal psychology of tyrants and in the nature of evil, and early Catholicism may have been the stimulus. Raised Catholic, we received theological training beginning in first grade. At that age the instructional emphasis often fell on the reality of sin. It is not much of a leap from sin to evil, from thinking about venial sin to pondering the worst mortal sins. Or maybe because I have so often been on the receiving end of goodness, I wonder how its opposite functions?

I think it’s been there since my Aunt Elsie read to me from the Book of the Martyrs. I have had an interest in the history, actions and personal psychology of tyrants and in the nature of evil, and early Catholicism may have been the stimulus. Raised Catholic, we received theological training beginning in first grade. At that age the instructional emphasis often fell on the reality of sin. It is not much of a leap from sin to evil, from thinking about venial sin to pondering the worst mortal sins. Or maybe because I have so often been on the receiving end of goodness, I wonder how its opposite functions?

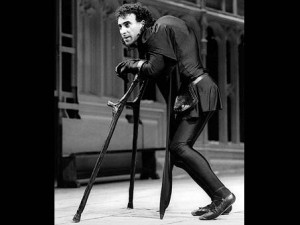

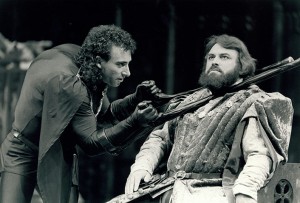

Anthony Sher as Richard III

I have lived a fortunate life. I have not lived under a tyrant or in a country enduring the after-effects of his actions. As with most Americans, on the surface, I am historically innocent. I have read enough to have an awareness of our nation’s dark places, our capacity for torture, for massacre, for intimidation and corruption but because we have striven to be a nations of laws (and paid the price in blood to do so), and because we have a stubborn democratic ideal that seems physically attached to us as citizens, we have avoided the worst damage our own home-grown brutes might have done.

Americans are not morally superior individuals just by dint of being Americans. That makes no sense and as arrogant posturing is  repellent and dangerous. How often have those who thought of themselves as repositories of goodness created hells on earth? Lord knows that our record with Native Americans, slavery, imperialism, rendition, and Abu Ghraib should set that thought aside. We are sinners all. Our brutes have been restrained from taking total power. Our democratic institutions and inherent distrust of the state have served us well.

repellent and dangerous. How often have those who thought of themselves as repositories of goodness created hells on earth? Lord knows that our record with Native Americans, slavery, imperialism, rendition, and Abu Ghraib should set that thought aside. We are sinners all. Our brutes have been restrained from taking total power. Our democratic institutions and inherent distrust of the state have served us well.

So why care about tyrants? Maybe the more we seek to understand the nature of earthly, daily evil, the better chance we have to recognize it when we see it and thus to oppose it and perhaps avoid its awful toll. Maybe because it seems inherently mysterious and unknowable and mysteries naturally attract us. Maybe because it has its own fascination. After all, why do we find Iago funny? Why does Richard III entertain us? Why could Hitler charm children?

How do we make sense of them as human beings with inner lives? I suggest we begin with the writer who seems to have known them best, and then use his creations in comparison with history’s powerful thugs. For example, Richard III is a great villain, one of the worst of Shakespeare‟s criminal-creations; to understand him, to place him into some kind of context, we can look at historical tyrants, and by this juxtaposition learn more both about Richard III and about those who used the power of the State to kill.

History can teach us how to see tyrants, how to listen to them, how to understand their manipulations and terrible, inhuman decisions. Literature can teach us how to see into and understand them. Literature can suggest the landscape of their inner lives. Thus From Richard, we can learn more about the real men who destroyed so many during this past century — for this Post, that means the Soviet Union and the three men most responsible for its terrible past.

History can teach us how to see tyrants, how to listen to them, how to understand their manipulations and terrible, inhuman decisions. Literature can teach us how to see into and understand them. Literature can suggest the landscape of their inner lives. Thus From Richard, we can learn more about the real men who destroyed so many during this past century — for this Post, that means the Soviet Union and the three men most responsible for its terrible past.

Olivier as Richard

II.

Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin were the 3 great architects of Soviet Communism.

In 1910 a political opponent said of Lenin that you couldn‟t deal with a man who “for twenty-four hours of the day is taken up with the revolution, who has no other thoughts but thoughts of revolution, and who, even in his sleep dreams of nothing but revolution.” *

To think only of revolution requires an ideological discipline, a framework that must govern what must be done after the  overthrow of the old order. It requires a ruthlessness in personal relationships. There are enemies everywhere. One must be wary and cold. The Revolution trumps the give and take and fragile balances of friendships and marriage. History demands that one’s human happiness be sacrificed to the triumph of the oppressed. Richard disposes of human beings as if their lives were of no importance.

overthrow of the old order. It requires a ruthlessness in personal relationships. There are enemies everywhere. One must be wary and cold. The Revolution trumps the give and take and fragile balances of friendships and marriage. History demands that one’s human happiness be sacrificed to the triumph of the oppressed. Richard disposes of human beings as if their lives were of no importance.

Trotsky

All of this is deadly. Backed by unrestrained power, any creed that so locks us into categories of the redeemed and the irredeemable can only result in dungeons and bullets. Fanaticism is the real devil. Absolutely focused ambition tied to a cold, remorseless will creates a Hell on earth. In their own words:

Lenin – March 19, 1922: “We must now give the most decisive and merciless battle to the clergy and subdue its resistance with such brutality that they will not forget it for decades to come….” *

That year, 2,692 priests, 1,962 monks and 3,447 nuns were murdered by the communists.

Lenin – January, 1918: “The dictatorship – and take this into account once and for all – means unrestricted power based on force, not on law.” *

Trotsky – 1932: “We must put an end once and for all to the papist-Quaker babble about the sanctity of human life.” *

Trotsky – 1932: “We must put an end once and for all to the papist-Quaker babble about the sanctity of human life.” *

In 1932, 6 million men, woman and children starved to death in the Ukraine in a state produced famine orchestrated by Stalin.

Ian McKellen as Richard

Stalin: “Death solves all problems. No man, no problem.” *

One brief instance of this maxim put into action: in July of 1938, Stalin is given a list of 138 names. He returns the list with “shoot all 138” accompanied by his signature. Another: a Soviet decree of April 7, 1935: children of twelve and over will be subject to “all measures of criminal punishment” including death. What can such a tyranny of unrelenting fear produce in families? in normal human relationships? Stalin’s inner circle was composed of Nikita Krushchev, Vyacheslav Molotov, Mikhail Kalinin, Anastas Mikoyan, Alexsandr Poskrebyshev.

This happened to members of their families as ordered by Stalin: NK’s daughter-in-law was jailed. VM’s wife was sent to the Gulag*. MK’s wife was beaten unconscious in interrogation and later sent to the Gulag. AM’s 2 sons were sent to the Gulag. AP’s wife was sent to the Gulag and shot — (the Gulag = the Gulag Archipelago, a system of hundreds of prison camps and prisons run by the communists and meant to contain criminals and political prisoners).

On being arrested, the invariable response of many of Stalin’s victims was Zachto? (Why? What for?)

Because there were quotas to fulfill. Because someone had been paid to denounce you. Because an enemy was settling a score.  Simply to exercise cruelty. To emphasize the use of terror as a psychological weapon. For no reason.

Simply to exercise cruelty. To emphasize the use of terror as a psychological weapon. For no reason.

Shakespeare’s Richard kills to advance himself (and he enjoys cruelty). Lenin, Stalin and Trotsky killed to advance themselves and to advance an idea –the dictatorship of the proletariat, the end of capitalism, the utopian vision (nightmare) of a communist world. Thus, their killing was epidemic. Killing in service of a utopian idea larger than any one person gives the killers a breadth of wickedness that Richard lacked. He killed a handful that threatened his advancement and possession of the throne. They killed millions.

Still, Richard’s psychology and perceptions help us see a Stalin more clearly. Both operated within the political sphere. Both possessed a will to power. Both saw themselves as alone and threatened:

Richard in Henry VI, Part 3:

Why, love forswore me in my mother’s womb;

And for I should not deal in her soft laws,

she did corrupt frail nature with some bribe,

to shrink mine arm up like a withered shrub,

to make an envious mountain on my back,

where sits deformity to mock my body;

To shape my legs of unequal size,

to disproportion me in every part,

like to a chaos, or an unlicked bear-whelp

that carries no impression of the dam.

Richard’s initial grievance is with nature. His form is an abomination to him as it has been to others. He hates a part of himself and thus chooses instead to master men and not love’s “soft laws.” His enemy includes nature itself, which began to afflict him before his birth. He believes himself a victim, one unable to be loved.

Richard’s initial grievance is with nature. His form is an abomination to him as it has been to others. He hates a part of himself and thus chooses instead to master men and not love’s “soft laws.” His enemy includes nature itself, which began to afflict him before his birth. He believes himself a victim, one unable to be loved.

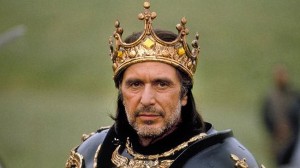

Pacino as Richard

He likens himself to an animal disconnected from its mother, “disproportion[ed]”, “withered”, deformed, mocked, forsworn.

From Robert Conquest’s Stalin: Breaker of Nations: “Describing Stalin’s Last Years: So Stalin enters his last phase, possessed even more than before by the demons of suspicion and implacability. He was beginning to have bouts of dizziness, and his psychological condition too continued to deteriorate. In 1951, in a moment of insight, Stalin actually said in front of Mikoyan and Khrushchev, though appearing not to notice them, ‘I’m finished, I trust no one, not even myself.’ His daughter writes that in these last years, he had forgotten all human attachments, he was tortured by fears which became a genuine persecution mania, and in the end his strong nerves gave way. But the mania was not a sick fantasy; he knew and understood that he was hated, and he knew why.”

Where does casual slaughter begin? If you are Richard, it begins with his body and his sense of himself within that body as “a chaos”. Perhaps he seeks order and psychological calm. For someone this damaged and self-pitying, for someone with such a deep sense of ugliness but also intelligence and ambition, what better way to seek such order than in aggression, in “command”? For disconnected from the possibility of love “in his [my] mother‟s womb”, Richard has no hope that another will love him.

For Stalin, perhaps it begins in his paranoia — I am this devious and merciless. Therefore, all those who surround me must be as I am. Therefore, I must strike first.

Am I a then a man to be beloved? O monstrous fault to harbor such a thought!

The reader also gets the sense here that Richard tries to see his life and the royal world around him in stark, cold, realistic terms. There is no idealism, no innocence left in him at all – if “this world [is] but hell, he can only “make his [my] heaven to dream upon the crown.” His hell becomes his heaven only when he has achieved the “glorious crown” — the absolute power to do as he pleases.

Some historians believe that Stalin lost whatever deeper humanity he may have possessed upon the suicide of his first wife. He wept at her grave and was disconsolate for a time thereafter, but he had been a killer before her death. Are their degrees of monstrousness beyond giving the order for the murder of one, a dozen, hundreds, tens of thousands? How do we enter such calculations within the minds of such men?

Stalin rejects any world but the Soviet Union and its enemies and any life but the one he can “hew …out with a bloody axe.” I think Richard and Stalin’s voice could be the same in these lines:

Then since this earth affords no joy to me

but to command, to check, to overbear such

as are of a better person than myself,

I’ll make my heaven to dream upon the crown,

and whiles I live, to account this world but hell,

until my misshaped trunk that bears this head

be round impaled with a glorious crown.

And yet I know not how to get the crown,

for many lives stand between me and home;

And I – like one lost in a thorny wood,

that rents the thorns, and is rent with the thorns,

seeking a way, and straying from the way,

not knowing how to find the open air,

but toiling desperately to find it out –

torment myself to find the English crown;

And from that torment I will free myself,

or hew my way out with a bloody axe.

Richard does not know “how to get the crown.” He rends and is rent on his journey to seek power, is lost and finds his way, grows desperate and tormented. Such volumes of frustration and inner fear must receive release, but Richard cannot show weakness. He survived the War of the Roses. He knows what happens to the weak. So therefore strike out; destroy one’s enemies so as to “free” one’s self from fear and uncertainty.

The glory of soliloquies by Richard and Iago, Edmund, Claudius, and Macbeth is that in imagining the inner lives of these villains, murderers all, Shakespeare gives the reader hope to achieve an understanding of other historical killers: Stalin, Mao and Hitler, Mussolini, Pol Pot, Mugabe and Hussein. Perhaps more than any other writer in the western tradition, Shakespeare understood the tyrannical mind that can coldly calculate the precise mask required so as to endure:

Why, I can smile and murder while I smile

And cry “Content” to that which grieves my heart,

and wet my cheeks with tears,

and frame my face to all occasions.

I’ll drown more sailors than the mermaid shall,

I’ll slay more gazers than the basilisk…

deceive more slyly than Ulysses could….

I can add colors to the chameleon.

Can I do this and cannot get a crown?

III, ii, l. 153-194:

Follow Shakespeare’s verbs: smile, murder, cry, wet, frame, drown, slay, deceive, add. Listen to how simply and clearly Richard lays out his confidence in his abilities to fool others and strike without remorse. He is speaking to us. He is charming us, as monsters sometimes can and will. What a feeling of joy is in this section. He is sly. He can fool others, but he wants us to know. Has there ever been a tyrant who did not believe he was a superior human being? But in believing that, listen to the price that must be paid:

Follow Shakespeare’s verbs: smile, murder, cry, wet, frame, drown, slay, deceive, add. Listen to how simply and clearly Richard lays out his confidence in his abilities to fool others and strike without remorse. He is speaking to us. He is charming us, as monsters sometimes can and will. What a feeling of joy is in this section. He is sly. He can fool others, but he wants us to know. Has there ever been a tyrant who did not believe he was a superior human being? But in believing that, listen to the price that must be paid:

And again:

“I…have neither pity, love, nor fear.

Then since the heavens have shaped my body so,

let hell make crooked my mind to answer it.

I have no brother. I am like no brother;

And this word “love” which greybeards call divine,

be resident in men like one another, and not in me.

I am myself alone.

V, vi, 67-83

Richard becomes like the anti-Job, the sufferer who curses Yahweh and who embraces darkness. He believes himself incapable of pity, that emotion whereby we extend our feeling of understanding to another. He believes himself to be utterly alone, as if he were another species: “I am like no brother.” Stalin too.

If no feelings of empathy connect him to anyone, if he cannot understand “this word love” on anything other than an intellectual plane, if he believes himself to be utterly cut off from all other human beings, “myself alone”, than why not kill anyone and all who thwart his will, multitudes if necessity demands it? They are not important. No one is important unless that person serves him. And as for the servant, how could he ever be certain of his master’s mind, will or heart, when the master himself seems not to believe in sympathetic connections? How does one confidently serve a master who sees a world of creatures alien to him?

What fills up someone bereft of love? Despair? Loneliness? Regret, if that is even possible? What does someone bereft of love but possessed of enormous power do with his time? Plot, anticipate and then act.

Facing a world that “affords no joy” to him but possessed of intelligence and will, why not “command…check…and overbear” everyone you can reach? Just as Richard does, just as Lenin, Tolstoy and Stalin did.

*Koba the Dread by Martin Amis