In a few weeks a handful of us, about 25% of our graduating class, will stand in front of mirrors and hope for the kindness of gentle lighting. We will stand in front of mirrors and look at the outline of our sagging faces and slopes of flesh letting loose and see again in our mind’s eye what we were at 18, members of a lucky species, the sons and daughters of America’s post- war generation of parents, just young enough to have escaped the Vietnam War, astonishingly innocent, as hopeful a class as America has produced. We will stand in front of mirrors and remember and get into our cars and drive toward a meeting of others like us, the lucky ones still here, the few who chose to attend, the ones who bear scars and white hair but the ones who made it this far, and we will remember.

All high schools are tribal because adolescents are tribal by nature.* Their desire to find a place and group where they will be accepted (or at least tolerated) is a powerful force. Bring them together in a building broken up into several years of grades (for us, it was 4), add athletics, mix in innocence, inchoate yearnings, desperation, sexual awakenings, intellectual ferment, the beginnings of an independent self, loneliness, lack of forethought, risky behaviors and automobiles, and a tribal identity is inevitable.

All high schools are tribal because adolescents are tribal by nature.* Their desire to find a place and group where they will be accepted (or at least tolerated) is a powerful force. Bring them together in a building broken up into several years of grades (for us, it was 4), add athletics, mix in innocence, inchoate yearnings, desperation, sexual awakenings, intellectual ferment, the beginnings of an independent self, loneliness, lack of forethought, risky behaviors and automobiles, and a tribal identity is inevitable.

This too, and perhaps in its own way of greater importance — has there ever been another 4 year span in our lives when we felt more deeply or grew more precipitously. High school retains its hold on many Americans because of all these factors, but the numbers of our graduating class probably intensified the experience. We were a small group of seniors, only 180, and a scattering of Catholics in a sea of public schools.

This too, and perhaps in its own way of greater importance — has there ever been another 4 year span in our lives when we felt more deeply or grew more precipitously. High school retains its hold on many Americans because of all these factors, but the numbers of our graduating class probably intensified the experience. We were a small group of seniors, only 180, and a scattering of Catholics in a sea of public schools.

John Kennedy’s election in ‘60, his youth and charm and Jackie, and then his assassination in’63 when he became iconic, seemed to drain much of the anti-Catholicism from the country, but most of us, as teenagers, were exposed to its residue in playground remarks (I fought a kid who called me a ‘fish-eater’ — well, we rolled around on the West Lawn Playground for a while before an adult broke it up).

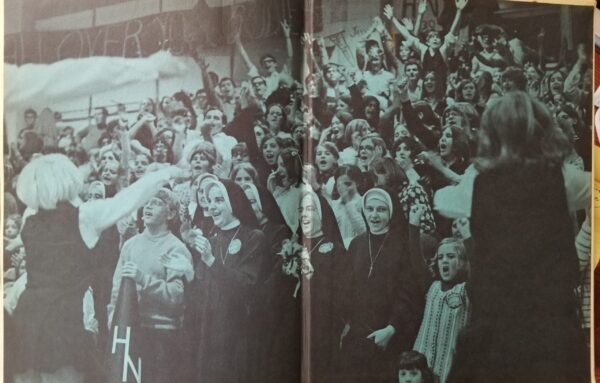

We were different. We knew we were different. That was part of our bond. We may not have been overly pious, but we went to Mass. We dressed in suit coats and ties and and the girls wore uniforms for school and we were thus instantly recognizable and set apart. Nuns and priests taught us. Our community was not a school district; it was a county and it was a single school.

We were different. We knew we were different. That was part of our bond. We may not have been overly pious, but we went to Mass. We dressed in suit coats and ties and and the girls wore uniforms for school and we were thus instantly recognizable and set apart. Nuns and priests taught us. Our community was not a school district; it was a county and it was a single school.

My God but we were so innocent. During our senior year, no member of our class committed suicide, died in an automobile accident, succumbed to a drug overdose.** In bandit packs, groups of boys took part in some ugly actions that now would have resulted in an arrest (I was a part of one of those packs). We got off with an apology.

We gossiped and told stories and lies and indulged in boasting but did not have to contend with the injuries and lifelong damage Facebook and Instagram and phones that take pictures now routinely cause adolescents. There is only one off-hand reference to computers in the entire 1970 yearbook.

We gossiped and told stories and lies and indulged in boasting but did not have to contend with the injuries and lifelong damage Facebook and Instagram and phones that take pictures now routinely cause adolescents. There is only one off-hand reference to computers in the entire 1970 yearbook.

But every tribe also has its outsiders, the ones who don’t fit, who walk through their daily school lives on the margins, who don’t meet the standards of masculinity or beauty or athleticism or academic accomplishment, who lack the confidence of the most popular. Our tribe had its bullies and supported a quiet kind of ostracism and sometimes added a mocking dismissal to the brew. We could be cruel to each other. If a teacher did not have a command presence, we could be merciless. Even now, 50 years later, I think about those who stood outside the various closed circles within the tribe and were lonely as a result. Adolescent loneliness is crushing. I think about instances of our treatment of some nuns and priests and lay teachers, and I am ashamed.

We often drove recklessly. One friend had a muscle car that held a V8 engine of 440 cubic inches. He routinely pushed it over 100 miles per hour on empty straightaways late at night. Another friend pressed a bug-eyed Sprite around blind corners as if he were a Formula 1 driver. I was a terrible driver until I matured. Somehow, we made it through.

We often drove recklessly. One friend had a muscle car that held a V8 engine of 440 cubic inches. He routinely pushed it over 100 miles per hour on empty straightaways late at night. Another friend pressed a bug-eyed Sprite around blind corners as if he were a Formula 1 driver. I was a terrible driver until I matured. Somehow, we made it through.

We were more free than seniors now. No parent could track us. We were out of contact for long periods of time. We rode all over Berks County in our fathers’ cars and gathered in parentless homes for TV and games but drugs were just beginning to enter our sense of what was possible, and I don’t remember instances of mass drunkenness until the night we graduated. Instead we talked, attended movies (Easy Rider, The Wild Bunch, MASH, Five Easy Pieces), played ball, talked some more, played RISK, gathered in our circle to watch bad horror movies on Dr. Shock Theater where a Philly no-name sweating greasepaint make-up hit minions over the head with a rubber chicken. We drove the back streets and long roads in darkness, talking, trying to figure everything out and our place in the mess of it.

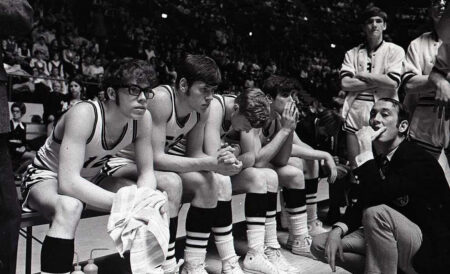

What I remember most vividly about our senior year was the sustained excitement of daily life lived just below the boiling point. We had access to cars. Our parents were letting us go. The class contained some of the brightest human beings I have ever known — individuals who possessed quick, agile, capacious minds. Finally, our class carried a concentration of superb athletes who produced 5 League Championships and 2 State Titles.

We gathered for the football and basketball games in roaring masses. Under the lights at Reading’s Municipal Stadium, huddled in the cold, watching smash-mouth football, released from the constraints of strict behavior, we howled for holes ripped in the opposing line by our friends rumbling over opponents like trucks gone out of control and Mike L. darting through, raising clouds of dust. Perhaps high school athletics have always been more primal than their college and pro counterparts. Most high school kids play for love of the game and for their teammates, not money or advancement.

Home basketball games were our crucible for that primal sense of theater and competition, more so than football because of the closed nature of the arena. We packed together and sweated and cheered with so much power one could feel a kind of transcendence at times, a melding into the crowd, into the joyful noise of teenagers (and nuns and priests and lay teachers and parents) letting go. In all my life, I have never felt more thrilled to watch any games than during our Championship season of 1969-1970.

Finally, if there is any group who deserve our special thanks, it is the nuns who taught us: the Sisters of The Immaculate Heart of Mary, of the Order of St. Francis, of the Order of St. Benedict, of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart. They were paid a pittance and lorded over by a clerical hierarchy who could never have done their jobs. They gave all of their lives to children, to us, and even at our hooligan worst, they never abandoned us.

It all comes down to this now, a bunch of 68 and 69 year old men and women gathering at a party to turn back 50 years to remember and reimagine 4 years of their youth, 5% of their lives. Those 4 years continue to hold some part of our hearts in a grip so strong that we will travel miles and miles for 1 evening to imagine it all over again.

What will come back to you as you drive toward Moselem Springs?

What do you wish now that you had done in those 4 years of Holy Name that you let slip away? Taken which chances? Stepped forward to try exactly what?

As you drive, I’ll bet, even now, a half-century later, that you can name the experiences that caused you pain, but please also recall, even now, a half-century later, those moments that give you such pleasure in their remembrance that you will break into a smile as you pull into the parking lot.

Seventy five percent of the class will not be at the reunion. They are scattered across the continent, uninterested, lost to contact or just gone. Who do you call back to mind and wish were attending? ***

It is not too late. The evening will provide a moment for action — for an extension of an extra kindness or an appreciation of the sweetness of temperament some still retain or perhaps even to begin a friendship. What will you take with you when the evening is over? There is not much time left but enough to make something new.

#This Post is representative of only 1 perspective of 180. As such it has gaps of knowledge and memory. It is also the point-of-view of a man, one who as a senior was not only shy and unsure of himself, but who was periodically afflicted by the boneheaded judgment peculiar to young men. One of the ladies in writing her evaluation of those years would unlock a viewpoint and insights unknown to me.

#Many thanks to Rick Hilton for his time in uncovering and converting them and for the use of his photographs.

*I have made repeated references to adolescents only because I made my living as a high school teacher and that is where my experience lies.

**I lost count of the number of children’s funerals I attended for suicide, OD’s, accidents.

***I think of Joey, Pete, Rick, Liz, Dennis.

Mr. Dobroskey, Holy Name High School, 1970: Post 300 – Every Good Morning (mikewallteacher.com)

D And The Worthy Life: Post 305 – Every Good Morning (mikewallteacher.com)

Coach Lloyd Wolf: Holy Name High School: Post 412 – Every Good Morning (mikewallteacher.com)

Giving Thanks #1: The Sisters: Coronavirus 11: Post 644 – Every Good Morning (mikewallteacher.com)