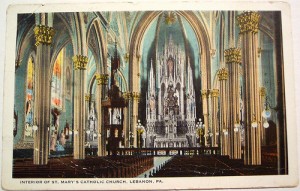

I know what my mother saw and did on Tuesday evening, June 4, 1929. Twelve years old, she performed “a piano duet with Miss Rita Hartnett” as part of an elaborate celebration honoring the golden jubilee of the priesthood of the monsignor of St. Mary’s Parish in Lebanon. She heard the Boy Scouts of St. Mary’s, “captained by … the smallest Scout in the Troop,” sing Uncle Sammy. She watched “girls of the first and second grade … clad in dainty yellow frocks … dance around a … decorated swing and sing to their Queen, Miss Jean Francis.” Only twelve years old, she witnessed “the outstanding number on the entire program … [as] given by the high school girls.” They performed a song and dance entitled The Mystic Gifts. “The spirits of Music, Flowers, Gratitude, Peace and Mercy met on their way to a secret mission.” *

I know what my mother saw and did on Tuesday evening, June 4, 1929. Twelve years old, she performed “a piano duet with Miss Rita Hartnett” as part of an elaborate celebration honoring the golden jubilee of the priesthood of the monsignor of St. Mary’s Parish in Lebanon. She heard the Boy Scouts of St. Mary’s, “captained by … the smallest Scout in the Troop,” sing Uncle Sammy. She watched “girls of the first and second grade … clad in dainty yellow frocks … dance around a … decorated swing and sing to their Queen, Miss Jean Francis.” Only twelve years old, she witnessed “the outstanding number on the entire program … [as] given by the high school girls.” They performed a song and dance entitled The Mystic Gifts. “The spirits of Music, Flowers, Gratitude, Peace and Mercy met on their way to a secret mission.” *

I did not expect to feel myself so moved by these images selected from a raggedly cut and crumbling and forgotten newspaper item. The years between then and now open their iron doors and there is my mother, so young it aches to imagine it, absorbed in intense life.

I did not expect to feel myself so moved by these images selected from a raggedly cut and crumbling and forgotten newspaper item. The years between then and now open their iron doors and there is my mother, so young it aches to imagine it, absorbed in intense life.

Her sisters and mother, her children and later, her grandchildren, her husband and her Catholicism inhabited the center of her life. They commanded her devotion. From that living, sustaining core, she spun out her own ‘mystic gifts’, ones that her children bear in our blood and in our characters.

On February 19, and March 5, 2006 my sisters and I sat down with my mother over breakfast and got her to talk about her young life, about how she had met Dad, how she lived, and what she missed. I took notes. She no longer remembers much, and those notes, plus our memories, and some newspaper clippings, have become the touchstone I am using to try to look back through time.

Her maternal grandfather whom she called Pam Pam was a shepherd who immigrated to the US from Germany in 1881. Her father was a locomotive engineer and as Irish as the name Aloysius O’Donnell can be. Our grandmother married at 17. Mom was born in 1917, one of five children and the youngest girl. They lived at 2408 Guilford Street in Lebanon, Pam Pam lived with them, and they made 8 people to a house with 3 bedrooms and no bathroom, just a wooden outhouse off the back yard and a “slop jar” under the bed for nights. There was no electricity or running water, just a back yard pump. Pam Pam spoke High German and slept in a feather bed elevated high off the floor. The balcony on the second floor back caught breezes, and she could reach it by what she called “secret stairs” from the kitchen. All her life she called her parents Momma and Poppa.

Her maternal grandfather whom she called Pam Pam was a shepherd who immigrated to the US from Germany in 1881. Her father was a locomotive engineer and as Irish as the name Aloysius O’Donnell can be. Our grandmother married at 17. Mom was born in 1917, one of five children and the youngest girl. They lived at 2408 Guilford Street in Lebanon, Pam Pam lived with them, and they made 8 people to a house with 3 bedrooms and no bathroom, just a wooden outhouse off the back yard and a “slop jar” under the bed for nights. There was no electricity or running water, just a back yard pump. Pam Pam spoke High German and slept in a feather bed elevated high off the floor. The balcony on the second floor back caught breezes, and she could reach it by what she called “secret stairs” from the kitchen. All her life she called her parents Momma and Poppa.

Monday was wash day. She ironed pillowcases and loved to see sheets blowing in the wind. Occasionally, her mother, Rose, but forever Nanny to her grandchildren, would give her a nickel on Mondays to go to the Jackson Theater for cowboy movies. Her oldest sister, Elsie, the sister who should have gone to the convent, made it through eighth grade but then had to go to work in a butcher shop. The family always had meat, but they never owned a car.

During the Depression, hungry men knocked on the back door. Nanny brought them a plate and they sat on the porch to eat. My older brother and sister remember this tradition continuing in Myerstown. Hobos walked up the lane from the railroad tracks, and Mom brought them food that they ate under the apricot trees in the back yard. She sold homemade penny taffy in the schoolyard and brought the money home. Nanny made donuts and Pam Pam sold them door to door. Gladys, her sweetest sister, worked hard “from day 1” cooking, cleaning, doing laundry and baking. Her layer cakes were so moist and good you almost wept from pleasure when you took a bite. We still use her recipes.

Her aunts and uncles were a constant presence in her life. Aunt Emma married a man who played a squeeze box, and who later told her that he had lodge meetings to attend when actually he had a girlfriend on the side with whom he had a child. Uncle Rudolph gave her 5 cents every time he visited.

Nanny converted to Catholicism long after all the children’s births. She walked to the convent and received instruction from a sister of the order of St. Joseph. Aunt Elsie made sure that Mom and Jimmy, the youngest, received first Holy Communion and confirmation.

Nanny converted to Catholicism long after all the children’s births. She walked to the convent and received instruction from a sister of the order of St. Joseph. Aunt Elsie made sure that Mom and Jimmy, the youngest, received first Holy Communion and confirmation.

However, Nanny could also be a tyrant. Mom remembered her father on his knees begging for forgiveness after she had caught him with a bucket of beer. She chased away Gladys’ beau and forbade Mom from dating, ever. With a hardheaded resolve that later made her a good match for my father, she refused.

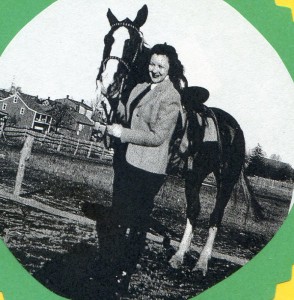

Mom and her favorite, Bobby.

She was the first child to graduate from high school, she dated a West Point cadet and she traveled to Philadelphia and Williamsburg with her girlfriends. She worked at Bell Telephone and eventually rose to become Evening Chief of the IndianTown Gap Board. She supervised over a dozen young women. She had ambition and courage. She was living at home but had asserted her own sense of independence. She broke the role of women imposed by Nanny on her older sisters, and she did so without alienating anyone. But she was also a young woman of the times. She told us that, “Politics never bothered me. I was too busy thinking about boys and horses.”

The photo where all her Irish roots show themselves off.

The photo where all her Irish roots show themselves off.

She dated a State Policeman named Francis Xavier Christine whom she called FX@. He was a superb horseman. He introduced her to horses and riding, among the most precious of her memories. Just short of 90 she took the reins of a two-seater carriage and joyfully drove along back roads near our home. Our friend, sitting next to her, told her that “she had good hands;” we should never underestimate the staying power of muscle memory.

Pretty and vivacious, spirited and smart, yet she did not marry. We do not know if there were any proposals before Dad’s. She never spoke of any. All around her, she would have seen friends marrying and beginning families. The years ticked by. At some point she had to have become worried – past 25, past 26, her future beginning to promise a life with her sisters and living with her parents until they died, all her freshness and vigor and yearnings subsumed into years of repressed service and very small pleasures.

She met Dad on a blind date, and on that first night, they went dancing. Very smooth of my father – he led with his best romantic skill. They went on group picnics at a Girl Scout cabin in the Blue Mountains where they grilled steaks (and took loads of photos). We don’t know how long it took them to fall in love. Not long I suspect. Whenever that occurred, he started to stop by her home, in uniform, for breakfast. From the first, Nanny liked him, and he loved her cooking. The man loved to eat, and the O’Donnell’s knew how to keep bringing it to the table. Elsie liked him because he was Catholic. She had been in St. Mary’s@@ when 4 or 5 Troopers from the Lebanon sub-station, my father among them, came to Mass in their uniforms. I think Mom understood that she was in love when she raced for the light at #549 on the Gap switchboard because she knew it was the State Police number, and Charlie might be on the other end.

She met Dad on a blind date, and on that first night, they went dancing. Very smooth of my father – he led with his best romantic skill. They went on group picnics at a Girl Scout cabin in the Blue Mountains where they grilled steaks (and took loads of photos). We don’t know how long it took them to fall in love. Not long I suspect. Whenever that occurred, he started to stop by her home, in uniform, for breakfast. From the first, Nanny liked him, and he loved her cooking. The man loved to eat, and the O’Donnell’s knew how to keep bringing it to the table. Elsie liked him because he was Catholic. She had been in St. Mary’s@@ when 4 or 5 Troopers from the Lebanon sub-station, my father among them, came to Mass in their uniforms. I think Mom understood that she was in love when she raced for the light at #549 on the Gap switchboard because she knew it was the State Police number, and Charlie might be on the other end.

We know that he had proposed by the end of March, 1946 because he left a copy of his letter to Captain Griffith’s, Captain of C Troop, stating: “I have the honor to respectfully request that I be granted permission to marry Miss Christine J. O’Donnell …,” and at #2, “If this request is granted, being married will in no way interfere with my duties as a Pennsylvania State Policeman.” He received his reply from the Captain on April 3: “Kindly be advised that permission has been granted for you to marry … and remain a member of this Force …” For better or worse, we live in an era that seems as far removed from this specific kind of official communication as the sun is from other stars. One more critical point – my father felt he had to assure the Captain that, really, the State Police would still come first. By implication, they would remain his principal family and the object of his steadfast loyalty.

From the poem The Man In Blue, referenced in The Search #11: “Twenty-four hours a day/No wonder his hair is gray!/He has to forget his kids and the wife/ Because he has sworn to give up his life/For you and you and you….” He never forgot his family, but I think he struggled to balance the demands imposed by both.

From the poem The Man In Blue, referenced in The Search #11: “Twenty-four hours a day/No wonder his hair is gray!/He has to forget his kids and the wife/ Because he has sworn to give up his life/For you and you and you….” He never forgot his family, but I think he struggled to balance the demands imposed by both.

Her memory of his proposal was sketchy. She thought Dad said something like, “Let’s go look at a ring.” He may have proposed in The Little White House Tea Room in Harrisburg. He left one of their business cards taped onto the same page as the 8 news stories and announcements recording their application for a marriage license, announcing the marriage, and describing the wedding. When he finally presented her with a ring, she didn’t like it, and she made him take it back. Everyone was in favor of the marriage.

We have no photos of the wedding. Our paternal grandmother made the arrangements for the photographer, but that jamoke forgot to put film in the camera. They married on a Monday morning in May. Mom wore a light blue suit and walked down the aisle with her father. Dad treated all the guests to a wedding breakfast at the LLanerch Country club where he had been an assistant pro. They left immediately for a honeymoon in Montreal and Quebec.

The Book contains nine postcards that chart what they saw and give the names of some hotels where they stayed. They drove through Stamford, Connecticut, through Boston where they stopped at the Bunker Hill Monument, cut west and north to Cooperstown, New York, where they attended Mass at St. Joseph’s Mission Church and then true north through Plattsburgh to Montreal where they saw the great steel cross on Mount Royal and walked through the Botanical Gardens. They drove north with the spring.

When they returned to Lebanon, they moved into a second floor apartment on Monument Park, a block from her parent’s home. It still has the balcony my older brother remembers. He can clearly recall sitting in a baby carriage and being pushed around the Civil War Monument. She spent lots of time with her family after her marriage because Dad’s patrol schedule was so demanding. Jack Kinsella, a fellow State Policeman, told me recently that at that time, in the course of a typical schedule, a Trooper worked six days a week and stood for Role Call even on his day off. They never had a night off before a day off. None of that changed with a Trooper’s marriage. A hard way to begin married life.

When they returned to Lebanon, they moved into a second floor apartment on Monument Park, a block from her parent’s home. It still has the balcony my older brother remembers. He can clearly recall sitting in a baby carriage and being pushed around the Civil War Monument. She spent lots of time with her family after her marriage because Dad’s patrol schedule was so demanding. Jack Kinsella, a fellow State Policeman, told me recently that at that time, in the course of a typical schedule, a Trooper worked six days a week and stood for Role Call even on his day off. They never had a night off before a day off. None of that changed with a Trooper’s marriage. A hard way to begin married life.

Their apartment and their view of the Park.

My mother became pregnant seven times in 13 years. She suffered a miscarriage in the doctor’s office; he baptized the fetus there, in her presence. Two of her sons died after birth, Thomas at 3 months; Patrick never made it home.

When Dwight Eisenhower was asked what event in his life most hurt him, the reporter expected him to speak of American deaths during the war or some similar occurrence. Instead he spoke of the death of his son at three years of age of scarlet fever.

We have a record of Thomas’ last day, and it circles back to the State Police. My aunt Gladys, who always came to help after Mom brought a baby home, said that he started crying and would not stop but also seemed short of breath. My mother called my father and then 3 teams of State Police cars, transferring to the new team at county lines, escorted the ambulance carrying my brother and a nurse. My parents were not allowed to ride in the ambulance but moved from cruiser to cruiser. The lead sentence gives the awful core of the story: “Death was the victor in a 75 mile race from Lebanon to St. Christopher’s Hospital in Philadelphia ….” And then this: “the infant died at 1 P.M., about 15 minutes after being admitted.” He died of a heart disorder. **

I think that we can be broken inside without ever saying those words. Instead, we deal with the present in all its demands and push the pain into some recess where it exists as a periodic and terrible crashing in pitch darkness, and all we can do is wait in the light for its memory to bring sudden jolts of pain. To the best of my knowledge, my mother never spoke of the impact of their deaths. She raised her children. She tended to her marriage. She embraced her faith. Her sisters and mother provided incalculable love and support. Rosemary followed Thomas in 1956 and Patrick in 1959.

We don’t know what happened to Patrick. My older sister clearly remembers a conversation with my mother just a few years ago where she described a baby born with spina bifida and even “flippers where his arms and legs should be.” We have his birth certificate and we know where he is buried — with Thomas. Very soon, my sisters and I will return to the cemetery and find out what happened to him.

Something changed in her after that. She became more anxious. She lost her confidence. Sometimes she would not sit on our front porch in West Lawn because she could not bear to have to speak to the neighbors. I think that within her, in a place she rarely revealed, is a core of unutterable sadness, the forever-burden of the death of children that she nurtured with her body and whom she saw perish. Henry Adams, the author of The Education of Henry Adams, once told friend that the “great calamities in life leave one speechless.” Later “he declared that ‘Wisdom is silence’.” # That last sentence makes the most sense to me. Talking about the past resurrects images. Why would any mother or father want to bring those back? What right does anyone have to know the depth of their pain?

My father buried the devastation of it. We never saw any sign of that shock. He never, ever spoke of it to us. Perhaps he took his grief to his priest. As I have previously written, after the death of a fellow officer he said, “You have to get used to these things.”

My mother at her most beautiful, wearing her wedding outfit, probably on her wedding day.

My mother at her most beautiful, wearing her wedding outfit, probably on her wedding day.

We moved to Myerstown sometime before I was born and lived in big wooden house on a 400 yard wide strip of farmland and one row of homes between old and new Route 422. There was no better place for us to grow up, especially as a boy. We played hide-and-seek in the fields, roamed the alley behind our house, explored barns, and walked ‘down the lane’ with our ever present Aunts who took such delight in our young lives that I don’t remember them ever not smiling.

We moved to West Lawn. She spent time with friends at our kitchen table. She kept her home spotless. Every year she made gardens awash in color. She and my father and another State Police couple traveled to Ireland. She celebrated her time with her grandchildren with unending joy. As my father aged and suffered bouts of ill health, she took care of him. In a few months she will turn 95. She has been robbed of her short term memory and much of her deep past, but bound to her wheel chair, she endures in a deep sweetness of temperament.

As a child she watched a presentation of songs and dances prepared for a priest including one song that described mystic gifts and their mission. Her gifts to us, those who survive, have been a love of flowers and nature, a wry wit that even now can surprise, a resolute patience, a devotion to her circle of family, a shatter proof love for all within that circle, and a facility with language and poetry. She wrote poems all her life, and even now her descriptions of visions that her brain conjures retain power. Visiting her recently she began a conversation that I followed with questions. I took notes as she spoke; I did not want to lose these sentences and their incantatory power: “He’s a man who walks through the air. He’s the man who counts the men who count. You need to find out who he is. It has to be someone who is almost magical because of the things he can do and the things he can say. There are magical things in the air that are ever magical. Magic people are in the air. I don’t know where they are. They don’t know themselves. They don’t just arise from nowhere and say I am he and I am she. All the other angels and spirits running around the sky make these things happen. The angels and spirits make my face soft.” I don’t know where these sentences originate except that somewhere within all the years she has lived she remains who she has always been, a woman whose love has been the purest and most selfless of anyone I have met, a woman whose entire body melts into her smile when one of her great grandchildren is placed in her lap and she says, “Babies! I love babies.”

This last photo shows Charlie and Chris, not yet our mother and father, on their honeymoon, sitting in the spring sun, young and mad for each other, and looking into the camera with whole hearts. Our hearts should rise in joy to greet them.

This last photo shows Charlie and Chris, not yet our mother and father, on their honeymoon, sitting in the spring sun, young and mad for each other, and looking into the camera with whole hearts. Our hearts should rise in joy to greet them.

*The Lebanon Daily News: June 5, 1929: “MSGR. Christ Honored By Parish Children.”

@His name appears on the Honor Wall at the State Police Museum.

@@ I have memories of attending Mass at St. Mary’s. Long since torn down for another mall style atrocity, it had a beautiful interior. In my child’s eyes, its vault soared up and up. I still associate the scent of incense with its huge space.

** The Philadelphia Bulletin, June 18, 1954.

# The New York Times Book Review: The Missing Pages by Brenda Wineapple; March 4, 2012

For an additional perspective on my parents, you can reference a previous Post, #8, “Earle And Alma, Charlie And Christine,” at my home site www.everygoodmorning.com