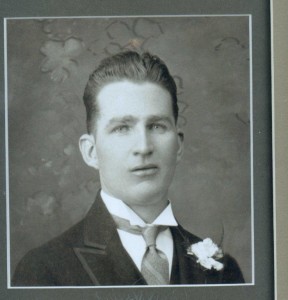

He looks directly into the camera, unsmiling, an unusual expression for a groomsman to wear. Why not a smile? He is so young. Sometimes his youth causes me to hold my breath. His gaze now carries across almost 80 years. All of his life awaits him. I still miss him.

He looks directly into the camera, unsmiling, an unusual expression for a groomsman to wear. Why not a smile? He is so young. Sometimes his youth causes me to hold my breath. His gaze now carries across almost 80 years. All of his life awaits him. I still miss him.

One of the reasons for my search for my fathers’ living presence in the past comes down to a question: Here’s his life, one among billions and billions. Here are all the paths that his life might have followed, choices that are incalculable in number. Within an immensity of possibilities, how did his one life find directions through the years? Looking back, what patterns can I discern? What did he choose? Why did he make those choices? These are the mysteries of his life, but also universal mysteries that apply to us all.

His father dead, my father dropped out of school and from 1930 to 1938, from ages 15 to 24, from boyhood to young manhood, he worked in Philadelphia to help support his family. There had to have been others in a nine year span, but we know of three jobs, apprentice photographer, and caddy at the LLanerch Country Club, now the Overbrook Country Club, where he worked his way up to assistant pro and taught golf. At LLanerch he worked for those people who had the money and leisure time to play the game in the Depression. He worked for those who had prospered. His upward movement at the Club suggests an evolving skill at the game but also tells us that he knew how to make others comfortable, how to ingratiate himself. Whatever wildness a fatherless boy from a large family had acquired would have been toned down at his work. Maybe he learned to be a storyteller while walking from green to green? He learned how to dance somewhere; he had a terrific sense of rhythm and beat. He was so smooth on his feet before he met my mother. Maybe he learned at the Club, an outsider granted entrée by members who had taken a liking to him. We have no stories from this time to offer us a glimpse of him. I have to fall back upon whatever logic can be worried out from might’s and maybes.

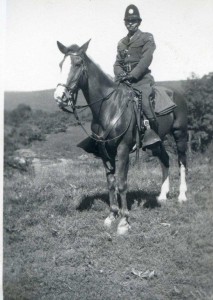

What led him to the Pennsylvania State Police? He never told us. He rarely spoke of his past at all. Somehow he found his path, his vocation that was never a job. I think that my father, a devout Catholic, a member of the Knights of Columbus, someone who kept his baptismal and confirmation certificates, who attended Mass and the Stations of the Cross without fail, found his version of the priesthood. Within the company of men, he could take the side of law and moral order. His maternal great Uncle, his Uncle and Grandfather were all police officers. His Great Uncle rode his police horse so well that he acquired the nickname “Straight Back Jack”.

So, the State Police offered the continuation of a family tradition, the safety of a state job, one where he could not be laid off, one where he could work all four seasons, a job that promised authority, status and upward mobility. Maybe he sought the romance of the uniform and the adventure of the chase. There is no indication that he had ever traveled very far out of the Philadelphia-Jersey Shore loop so there had to have been the lure of other places, the natural urge of the young to escape home for adventure.

My father left little that described the processes necessary to join the State Police or the training he received once accepted, but others have done so. Two oral histories available on line have been very helpful in creating a bridge to understand my father’s probable experiences.

Harold Trout, like my father, born in 1914 and a Philadelphian, entered his training in 1937. Rocco Urella, who eventually became the Commissioner of the State Police, entered in 1938, the same year as my father but as a member of a different class. Their memories of their training provide a portrait of daily life as my father would have experienced it.

According to Trout, the State Police had created an entrance process that made a professional, standardized attempt to evaluate a man’s qualities, perhaps in response to the rumored corruption of the Pennsylvania Highway Patrol’s acceptances which were said to be based on political connections and cronyism, but for admission to the State Police — “….politics couldn’t get you in, and you had to get in on your own merits.”*

Trout took his entrance examination in Reading. There were physical requirements to be met. Every candidate had to be at least 5’9” tall. He had to have good teeth, good eyesight and be at least 21 years old. Of course, in 1938 he had to be a he. The written test was immediately followed by a personal interview conducted by Sylvius Overmiller, as Teutonic a name for a gatekeeper as one could make up. The interview consisted of what if questions — What would you do in x situation? What would you do if Y did Z? At the end Overmiller turned around in his chair and asked Trout to describe his tie, its color, shape, etc. My father must have done well on the exam and made a good impression on the interview for he was accepted into the April, 1938 class.

Upon arriving at Myerstown***, my father would have been subject to an immediate physical exam. He would have been issued towels, 2 pair of riding jodhpurs, fatigues, and used shoes and socks; the State cut where it could. He would have had to provide his own underwear. They were given Wednesday nights off and leave every other weekend.

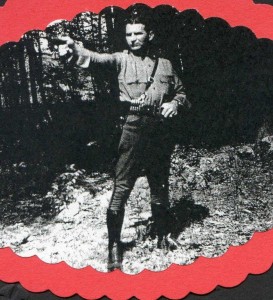

For three months they were under continual pressure with classes in swimming, typing, geography, criminal law, fingerprinting, English, horseback riding, weapons training, pistol qualification@, boxing, jujitsu, and wrestling. My father was never the wrestling-with-his-kids type, but once he showed me a simple move that an officer could use to physically restrain a suspect who was resisting arrest. This all happened very fast. He placed his hand over the back of my hand, the bottom of his palm resting on my knuckles. His index finger and middle finger extended down my forearm. His pinky, fourth finger and thumb locked around my wrist. He applied pressure. With minimal effort, he immobilized me. If he had to do so, he could snap a wrist bone.

They began each morning with a two mile run. They alternated lectures with physical training throughout the day, but “there was no such thing as a typical day … which made this job …interesting….”**

No matter their instructor, they were told again and again that there was no unit comparable to the State Police: “It was the sort of thing that the Marine Corp is; the first day they go into training, they’re taught that the Marine Corp is the best military outfit in the nation. It’s bred in them; we were taught the same about the State Police, that we were the best there was.” *

The psychological training was intense. They were trained to take criticism from a mob so as to always keep their composure. At any time individuals would be singled out and multiple instructors would descend and scream at them, “Coward! You’re Yellow!” * and any curses they could improvise. They “criticized you unmercifully.” *

Their riding instructor, Sergeant Huswar, another German, impressed upon them the necessity of controlling their horse at all times. They had to learn how to ride so as to be ready for crowd control situations at strikes, demonstrations, riots.

They rode with saddles and bareback. Their bouncing produced blisters. They learned that a horse was more valuable than they were for “… a new man could be had for a three cent stamp, but a horse cost three hundred dollars.”* After a full day in the saddle, they had to care for their horses before they could shower or eat.

Each cadet “had to memorize and recite the Call of Honor at Graduation.”** My father pasted a copy of the Call in The Book##:

Each cadet “had to memorize and recite the Call of Honor at Graduation.”** My father pasted a copy of the Call in The Book##:

I am a Pennsylvania Motor Policeman, a soldier of the Law. To me is entrusted the Honor of the Force. I must serve honestly, faithfully, and if need be, lay down my life as others have done before me rather than swerve from the path of duty. It is my duty to obey the Law and to enforce it without any consideration of class, color, creed or condition. It is also my duty to be of service to anyone who may be in danger or distress, and at all times so conduct myself that the Honor of the Force may be upheld.

This is an oath, a sacred call to be of benefit to the greater good. Look at its key words: soldier, the law, honor, duty; in the fourth sentence, an implied absolute fairness followed by service and sacrifice. My father joined an organization that was larger than his personal concerns. No matter how flawed in practice, he could believe that he was working on behalf of justice and for the safety of ordinary citizens.

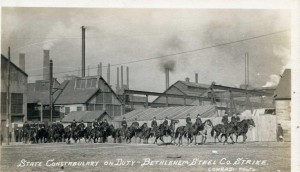

He loved the history of the State Police. He collected 24 State Police postcards that showed photos of the Force in action during the Bethlehem Steel Strike of 1910. He found a group photo and company roster of Troop C, then stationed in Shillington in Berks County; he spent many years as a member of Troop C. Along with providing for his family, the State Police gave him the grand purpose of his life and perhaps his most passionate love.

He loved the history of the State Police. He collected 24 State Police postcards that showed photos of the Force in action during the Bethlehem Steel Strike of 1910. He found a group photo and company roster of Troop C, then stationed in Shillington in Berks County; he spent many years as a member of Troop C. Along with providing for his family, the State Police gave him the grand purpose of his life and perhaps his most passionate love.

I remember so clearly how he looked in his full uniform – straight, formidable, professional, shoes polished, tie straight and knotted full to the collar, his Sam Browne belt aligned in a perfectly angled leather slash across his chest, his sense of the requirements of honor revealed each day in the sharp relief of his dress and figure.

After three months, the first phase of his training complete, he was assigned to a substation for a second round of training — three months on the job as a “student recruit”: “You ate at the substation, and you slept at the substation. You got one night off and one day off a week only.”** His meals, uniforms, shoes and three pair of socks were provided. He was paid only $90 a month, $3 a day, but he had friends, camaraderie, the appreciation of those communities he would serve, self-respect and a day-to-day life that promised the unexpected. He had finally begun his own life away from his family as a man among other men.

*Trout: http://psp-oralhistory.com/interviews/pdf/trout/Trout_Harold_INTERVIEW.pdf

**Urella: http://psp-oralhistory.com/interviews/pdf/urella/urella-pdf2.html

***The training sites shifted – Trout was trained in Hershey and Urella at Albright College, perhaps at its Myerstown location before it shifted to its Reading location.

@Initially, he carried the standard police issue 38 caliber, six shot revolver with the four inch barrel. He was also trained in the handling and use of shotguns and rifles. He earned a sharpshooter’s designation in 1957 with a 30 caliber rifle.

##I was wrong about the authorship of The Book. I no longer believe that my mother or grandmother put it together. I think my father is its author. Too many of its newspaper articles predate their meeting and marriage; I also can’t imagine that my mother would have cut out two articles that reference a previous girlfriend. I think my father, a man with an eighth grade education and fatherless, was proud of what he had accomplished and thrilled at seeing his name in print in descriptions of his actions as a Trooper. He never spoke of his accomplishments, ever. If anyone was the precise opposite of a braggart it was him. He could be self-effacing to the point of utter silence. He never showed us this Book. It gathered dust in a cabinet next to my parents’ bed.