Stories bring to light individual histories; they tell the world that we were once awash in life, and thus they not only yoke us to others but also give us a fraction of earthly life after death. A story well told gives breath and movement to the dead. They walk among us, upright and once again in love with their days. The once lost stories of my father that I am discovering on a daily basis have made his presence real again to me.

Over 35 years he was stationed in Ephrata, Elverson, Reading, Hamburg, Pottsville, Pine Grove, and Indiantown Gap. He was a detective in the Criminal Investigation Division while stationed in Lebanon. He served on security details at Eastern State Penitentiary, as a bodyguard and driver both to a Governor of Pennsylvania, and to film stars on bond drives during WW II. Loaned out by the State, he served as a driver and as security for the Governer of Virginia at the Democratic Convention held in Philadelphia in 1948. He evaluated nervous drivers as they made their way around the test course. He arrested chicken thieves and safe-crackers and forgers and went out on manhunts for murderers.

Two hundred eleven stories that tell something about my father compose The Book, the majority of them newspaper clippings from The Lebanon Daily News, The Reading Eagle and Times and The Philadelphia Inquirer.* In addition, go page by page through The Book and certificates, photos, carbon copies of letters, postcards, and payroll stubs reveal themselves – all of this is gold, and its light traces the frameworks of both the shadows and the clean, stark lines of a long era of my father’s life, from 1938 to 1965 (he served until 1973).

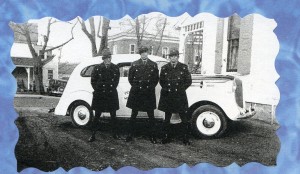

My father (on the right) and two other Troopers standing in front of a Ghost Patrol car outside the Elverson substation.

The first news story in The Book is both somber and illustrative of the military ritual that permeates the Force. Two photographs record the respect paid to a State Policeman who died in the “line of duty” in June of 1941. Rows of officers stand at attention outside a church while Trooper pallbearers convey the coffin down the steps. Trooper Thomas Carey was “overcome by chemical and smoke fumes while attempting to rescue a man and a woman trapped in a blazing automobile after a collision on Route 22, east of Bethel.” My father is shown with five other officers “firing [sic] a salute over Trooper Carey’s grave.”* Twenty one State Policeman died in action during my father’s service, six of them shot to death. In full uniform, he attended many such services.

The first news story in The Book is both somber and illustrative of the military ritual that permeates the Force. Two photographs record the respect paid to a State Policeman who died in the “line of duty” in June of 1941. Rows of officers stand at attention outside a church while Trooper pallbearers convey the coffin down the steps. Trooper Thomas Carey was “overcome by chemical and smoke fumes while attempting to rescue a man and a woman trapped in a blazing automobile after a collision on Route 22, east of Bethel.” My father is shown with five other officers “firing [sic] a salute over Trooper Carey’s grave.”* Twenty one State Policeman died in action during my father’s service, six of them shot to death. In full uniform, he attended many such services.

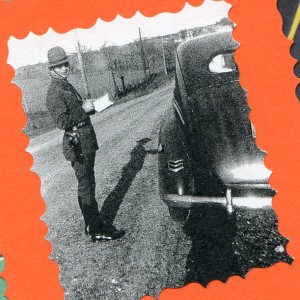

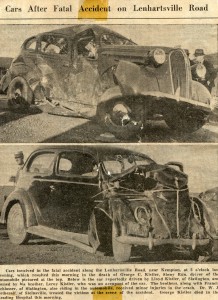

Eighteen stories in The Book report his involvement in traffic accidents as an investigator, as the patrolman first on the scene, and as a driver of the badly injured to the hospital. He had received serious training in the administration of first aid. I wonder how long it took him to learn how to control his emotions at what were often bloody and awful scenes. Three months of Academy training would not have done the trick.

Eighteen stories in The Book report his involvement in traffic accidents as an investigator, as the patrolman first on the scene, and as a driver of the badly injured to the hospital. He had received serious training in the administration of first aid. I wonder how long it took him to learn how to control his emotions at what were often bloody and awful scenes. Three months of Academy training would not have done the trick.

Again and again the newspaper stories detail the extent of the injuries in such accidents. At an accident in Kempton, “the top of [a victim’s] head was almost completely cut off and his jaw was fractured.”* This injury was the result of his automobile being “struck broadside and knocked a distance of 30 feet after which it continued to roll another 28 feet.” My father was first on the scene, and in an era of few available ambulances in rural Pennsylvania, he took three others with “severe body bruises” and “chest injuries” to an Allentown hospital in his patrol car. All of them survived.

There are some sentences that bring us into the immediacy of the landscape: “Private Wall said that Henry was driving with his head out of the front window because of the ice frosted windshield.” *

In another accident a “75 year old former miner for the Bethlehem Mines at Cornwall” was struck by a car as he walked home on a Sunday night. From that opening spins out a compressed story of the victim’s last moments and his larger life using details both dramatic and intimate. He was struck at night “when there was heavy traffic passing east and west. The man fell in the center lane of the three-track highway with his feet lying across the edge of the north track.” My father stood above his body with “a flashlight and … warned motorists to slow up so they would not run over the prostrate form.” I need to quote in full to give the reader a sense of the sometimes florid nature of the newspaperman’s prose:

“Scores of motorists stopped after passing the scene of the accident to learn what had happened, and at first glance were appalled by the sight of gory looking material near the body which looked like blood and brains in the eerie moonlight. Closer scrutiny revealed that the bloody looking material was nothing more than tomatoes which had been jolted from a lunchbox the man seemed to have been carrying. The fruit smashed when it struck the concrete highway. The receptacle was found at the side of the road, and the man’s felt hat was found on the highway about three car lengths away from the body. One of the cars which came to a stop at the scene contained a nurse who could discover no pulse and expressed the fear that the man was dead, although she warned that in fractured skull cases the pulse fades to a low point before death ensues. Those who took charge, however, assumed the man was dead and sent for the state police rather than an ambulance.”

The victim’s daughter said “that since retirement her father spent much of his time in rambles about the city and often into country roads. He was on such a hike apparently when he lost his life. His wife, Sarah, died several years ago.” All seven of his children are named. He had “21 grandchildren and three great grandchildren.”**

What good fortune we have had as his children that my father preserved this story for us: here he is, in this singular moment of time, in the middle of a tragic drama, standing over this poor man, waving a flashlight to oncoming traffic. I imagine all of this is somehow emblematic of the intensity of his life as a police officer.

He saw every variety of injury. From another story: “… her uncle suffered a possible fractured skull, multiple brush burns of the body and contusions of the right cheek and eye. Miss G. suffered lacerations of the mouth and nose, lacerations of the left leg, shock, and fractures of the femur and lower left leg and the pelvic bone. Mrs. HB suffered … deep lacerations of the left forehead … and a puncture wound of the left leg…. GD had his front teeth knocked out….”* Story after story describing traffic accidents show men and women and sometimes children thrown from the car or “catapulted through the windshield.”* He would have arrived in the aftermath of the violence to witness crunched, smoking cars and trucks, maybe fires, screams, blood everywhere, panic. He would have had to work on grievously injured children such as the four year old girl thrown “through the front window”* when her father’s car overturned. He had to learn to combine professional detachment and a comforting, secure presence into one fluid set of competent behaviors. Lives depended upon his immediate actions.

My father had to quickly tend to the victims while setting up flares. The early cars had no two way radios. He or another Trooper or a civilian would have made the call to both a hospital and their station. These are the years before 911. The response time would have been slower, especially in rural areas. Maps were often inaccurate, and rural route addresses inexact, geographical guesses rather than certainties. Therefore whether seriously injured victims lived or died would often have depended upon the actions of the first State Policeman to arrive.

My father had to quickly tend to the victims while setting up flares. The early cars had no two way radios. He or another Trooper or a civilian would have made the call to both a hospital and their station. These are the years before 911. The response time would have been slower, especially in rural areas. Maps were often inaccurate, and rural route addresses inexact, geographical guesses rather than certainties. Therefore whether seriously injured victims lived or died would often have depended upon the actions of the first State Policeman to arrive.

The presence of World War II hangs over many items in The Book. State Police Commissioner Lindsay Adams “put out an order forbidding any men to volunteer to enlist in the Services; even to the point where they were classified on the records as deserters.”*** On Monday, December 8, my father walked a few doors down from the Lebanon Substation and tried to enlist in the Navy. When they rejected him because he was a Trooper, he walked next door and tried to enlist in the Coast Guard. He was given the same answer. Adams’s official order was in effect for six months; draft boards classified State Police officers as vital to the home war effort. After July of 1942 none of us knows of a story that describes my father’s actions or state of mind; however, a carbon copy of a letter dated September of 1940 from my father to the Commanding officer of Troop C in Reading requesting a transfer offers some insight. He desires to be transferred to Troop F in Lancaster so as to have more immediate access to his family in Philadelphia. # He was “contributing an average of $60 per month towards the support of my mother who is a widow … and my younger sisters and brothers who are 13, 14, 19 and 24 respectively….” He expected that “conscription would effect [sic] my two brothers and that would leave the responsibility of supporting the family entirely up to me, and by being stationed closer to home I would be able to contribute a larger sum toward their support and education and also would be able to observe their general welfare more closely.”@ There is no record of a response; he was stationed in Ephrata at one point, but we don’t know when. He never served in Lancaster.

My father, second from the left, sitting on the steps of the Lebanon substation.

My father, second from the left, sitting on the steps of the Lebanon substation.

Half a dozen news clippings in The Book chart the death of a friend in combat, the wounding of another, the award of military badges of honor and the formation of “flying squadrons … of State Motor Police in four Pennsylvania areas, including this city [Lebanon] to combat parachute troops and meet other emergencies.” Three hundred and fifty troopers “fully armed with machine guns, tear gas and rifles … will rush to any trouble spot in the State.”* No names are mentioned but my father dutifully cut out the story and an accompanying photo where he might be one of four troopers in winter gear, armed with rifles and shotguns and standing in front of a ‘ghost car`, an all-white patrol car. I know of one other story from this time. We were at war with Germany. My father was part of a raid on a farm in northeastern Berks County where they broke down the doors of a barn and interrupted a Nazi Bund celebration of Hitler’s Birthday.

*A note on the clippings: the dates on many have been cut away as have newspaper identifications. Sometimes I had to make educated guesses on the years of some events. However, anytime I quote from a news story, the sentences, etc. will appear in quotation marks. Newspapers were the primary source of information on daily, local, national and international events. They had the money then to hire lots of reporters and assign them to their own beats, chief among them the crime or police beat; one way those reporters competed for space lay in their use of much more vivid, personal descriptions than one would expect to find in a daily newspaper today. Many of the stories represented in the clippings have a novelistic flair to their prose.

** This story came from the Lebanon Daily News. I have not changed one word of the quoted material. This is a news story, not an obituary. Amazing.

*** http://psp-oralhistory.com/interviews/pdf/trout/Trout_Harold_INTERVIEW.pdf

# I don’t know for sure why Lancaster would have been a posting that would have helped him better take care of his mother, etc. He never spoke of this. I can only guess – before the construction of the Turnpike, Route 202 and the Schuylkill Expressway, Routes 23, 30 and 3 offered straight shots into or close to his Philadelphia neighborhood. I don’t think he owned a car at this point. Bus service would have been cheap and regular. With only one day off a week, he had to find a way to maximize his time spent with his mother and family. Twelve years after his father’s death, he had almost certainly become a surrogate father to his younger brothers and sisters.

@ A letter dated September 12, 1940, authored by Charles Wall. As near as I can figure out, he was making about $1190 a year in 1940 or about $100 a month, gross. He was sending 60% of his pay to Philadelphia every month. A 1942 copy of his taxes lists his mother as a dependent and shows a yearly contribution of $400 from a gross salary of $1290 – 31% of his income.