Walk quietly along a game trail in a dark forest under dark skies and the filaments of spider’s webs will catch you — their adhesiveness and strength will keep some fragment of them attached, and though you stretch and pull them away, threads will stick, and you will carry them with you. In the same way stories lie ready to fasten themselves onto us. Our paths on a quiet day suddenly thrust us into another kind of life or death to consider. Some stories, like this one, repel light, and so maybe the only time to tell it is in this kind of mucked-up dishwater colored winter.

Walk quietly along a game trail in a dark forest under dark skies and the filaments of spider’s webs will catch you — their adhesiveness and strength will keep some fragment of them attached, and though you stretch and pull them away, threads will stick, and you will carry them with you. In the same way stories lie ready to fasten themselves onto us. Our paths on a quiet day suddenly thrust us into another kind of life or death to consider. Some stories, like this one, repel light, and so maybe the only time to tell it is in this kind of mucked-up dishwater colored winter.

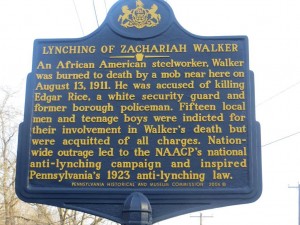

Every Thursday my car descends Route 82 sinuously from farmland into Coatesville. Curve follows curve. Eight-tenths of a mile from Route 30 the skeletal forms of a PECO transmission station shoot up on the right on a rise. The dark blue Historical Society Marker registers as a blur that says something happened here and then is gone. Last week I snapped the car over into the PECO driveway, drifted to the gate and parked. Scrub land circles the station. Stunted trees, viney brambles, puddles, gravel, mud. None of the homes to the west look more than 50 years old, but gone now, the Newlin farmhouse then stood opposite this place.

In a wretched irony of history that good novelists would not trust as an honest invention, the sign on the PECO gate reads in all caps DO NOT DISCARD ANYTHING ON THIS PROPERTY.

This is what happened.

Zachariah Walker had confessed to killing Edgar Rice, a steel company police officer, in self-defense on the night of August 12, 1911.

Walker had been drinking. A confrontation with Rice ensued. There were no witnesses to the shooting. He was arrested and taken to the hospital after he had tried to kill himself.

A mob dragged him from a hospital bed on the following Sunday evening and burned him alive on a pile of “split-rail fence posts and straw from a  nearby barn.” About 2000 Coatesville residents witnessed all this; some of them had “left church services to join the crowd.” That crowd was mannerly – “men stepp[ed] aside to allow women and children a better view of the burning.”

nearby barn.” About 2000 Coatesville residents witnessed all this; some of them had “left church services to join the crowd.” That crowd was mannerly – “men stepp[ed] aside to allow women and children a better view of the burning.”

No one tried to stop it. After the fire cooled, some people collected his bones as “souvenirs”. *

The next day children gathered at the remains of the lynching.

Chester County authorities actually moved on the case. Fifteen men were indicted for murder including complicit police officers. All were acquitted.

I don’t think Walker left anyone behind; Rice, a wife and 5 children. His memory continues to the present in the form of great great grandchildren. Walker has a marker; indelible images exist of his end.

William Faulkner wrote that “history is not [a] was ; it is.” It breathes next to us in the living bodies of descendants, in stories and ruins, in faded scraps of newsprint, in both court documents and collective memory, and on steel signs sunk alongside two lane roads where anyone might pull over and stretch up and read them. Once they sink themselves into our imaginations, they cannot be pulled away. Inside a searing neuron it is forever a summer night in August of 1911.

* “A CROOKED DEATH“: COATESVILLE, PENNSYLVANIA AND THE LYNCHING OF ZACHARIAH WALKER by Raymond M. Hyser, James Madison University and Dennis B. Downey, Millersville University

The Tuskegee University Lynching Map of the United States; Without Sanctuary web site; Strange Fruit by Billie Holiday