In the late 80’s my first wife and I were hurrying along at night on a side street near the Theater district somewhere near 8th Avenue; we had just been crudely accosted by two beggars, one joining another within the span of a block. Troll-like, they pushed themselves into our physical space and would not back off until, frightened and turning in a blind response to face them, I hunched my shoulders and like a feral dog, physically growled and bared my teeth. I think I even barked.

In the late 80’s my first wife and I were hurrying along at night on a side street near the Theater district somewhere near 8th Avenue; we had just been crudely accosted by two beggars, one joining another within the span of a block. Troll-like, they pushed themselves into our physical space and would not back off until, frightened and turning in a blind response to face them, I hunched my shoulders and like a feral dog, physically growled and bared my teeth. I think I even barked.

(Union Square Farmer’s Market)

We had been walking very fast and both of us were tall. They were sufficiently shocked for just long enough for us to turn and lope away, but as we did so, we saw more skels who seemed to be watching us, sliding into and out of the darkened doorways of store fronts. We left the sidewalk and walked in the center of the empty street until we hit 7th Avenue which had street traffic and pedestrians.

Now, smiling, engaged crowds sit and stroll and stand and talk in the public spaces and parks and squares. Runners, bicyclists and walkers use Central Park with almost a complete freedom from fear. Side streets and subways no longer feel like a no man’s land where only fools would venture without their eyes sweeping and critically evaluating everyone within a forward-moving space: how many are in that group of kids? is that scruffy guy in the line of our direction? what will I do if he seems threatening? who is behind us? how close are they? how many feet until safety? Safe in Central Park

The only time I felt any anxiety on this trip came late one night when we turned east from 10th Avenue onto 33rd street and into an empty area of storage depots and warehouses. I could feel the cold breeze from the Hudson on my neck. Dim yellow lights barely illuminated the shadows. The street was empty. My head swung back and forth, front and back, searching. Occasionally, while walking, I turned smoothly in a complete circle. Patti and I were almost jogging. I tried to puff myself up to make my largest silhouette – chest out, spine straight as a plumb line, a dangerous 59 year old.

The only time I felt any anxiety on this trip came late one night when we turned east from 10th Avenue onto 33rd street and into an empty area of storage depots and warehouses. I could feel the cold breeze from the Hudson on my neck. Dim yellow lights barely illuminated the shadows. The street was empty. My head swung back and forth, front and back, searching. Occasionally, while walking, I turned smoothly in a complete circle. Patti and I were almost jogging. I tried to puff myself up to make my largest silhouette – chest out, spine straight as a plumb line, a dangerous 59 year old.

(the Flatiron Building and Steichen’s 1904 portrait)

Nothing happened.

The old dread seems gone. Manhattan feels safe. Unlike the outlaw days of 25 and 30 years before (and longer), when a walker always carried an omnipresent alertness because he or she believed it a necessary precaution to escape a mugging or worse, now the innocent wander about, smiling and laughing in their throngs, their innocence no longer a death wish.

Lounging on the wall outside the Guggenheim, riding the subway uptown and downtown, looking for open galleries in Chelsea, striding along window shopping in the West Village, walking across Central Park, waiting for our show in the squares around Lincoln Center – none of these places, day or night, provoked hyper-alertness and alarm. Even sitting in Times Square drinking coffee at midnight, lit as if it had found a home on the surface of the Sun, watching a group of 5 or 6 wired white boys in red bandannas and ripped t-shirts in 40 degree cold walking at a fast trot, screeching and high as bloody kites, even that crew only caused a few of us to turn our heads and watch, out of curiosity.

On a bright, cold morning we walked among a multitude of often giddy shoppers in Union Square at Broadway and 17th street. We were there for the Farmer’s Market; the varieties of breads and fruit alone had me making both low hungry noises and trying to figure out how to buy an apartment close by so that I could act like an Italian or Frenchman and shop for fresh food in the open air each day. The press of the crowd, its jabbering vitality and color, added to the deep liveliness both of us felt.

We met a pleasant, bundled man walking his dogs, a westy and a golden doodle, who joined us for a block and told us how he often played dead with his dogs on the floor of the apartment, and that they took his playing as a sign to revive him by licking his face, but how he now had to rethink his game since the golden had licked the face of a sleeping, homeless man and completely “freaked him out”. In New York, as elsewhere, dogs act as one universal pass to conversation.

We walked past the Flatiron building of Steichen’s cryptic photo to The Strand Book Store, hot and jammed with men and women my age and younger; it was such a joy to see teenagers and twenty year olds with novels and histories wedged under their arms waiting in line to checkout.

Then we rode the subway to Cortland Street and Ground Zero.

Then we rode the subway to Cortland Street and Ground Zero.

The sun was gone, and the wind had picked up; it was much colder. Under lead-grey skies we waited in line on Vesey Street to enter the 9/11 Visitor’s center for free tickets to enter the 9/11 Memorial. We waited next to St. Paul’s Chapel, a dark stone church where Washington had prayed. Police officers, firemen, EMT’s and military personal did not have to wait. They were handed tickets and could immediately enter. No one complained.

Facing us to the south, flanked by cranes, new glass towers rose where the Twin Towers had stood. I thought of the normalcy of the hundreds of us calmly standing in line, the mark of a civilized city, as contrasted with what had happened here and farther south on September 11. The North tower was struck at 8:46, the South at 9:03, the Pentagon at 9:37 and the plane crashed at Shanksville at 10:03 – every American’s life became irrevocably bent out of his or her peaceful future in the space of that one hour and seventeen minutes. It is a wonder that we have not lost track of all we have seen and done in these ten years….

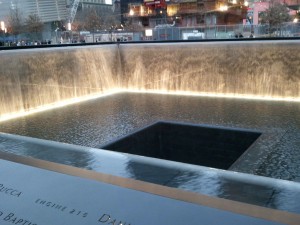

(the Fountains at Ground Zero)

(the Fountains at Ground Zero)

We stood together on this dark afternoon, a pleasant, chatty line of Americans and Germans, French and Brits, and watched a man dressed as Santa Claus try to figure out a subway map. A couple stepped out to help him. I wonder if other city dwellers who have been suddenly ripped into a new world by terrible acts also later experience this surreal sense of place, as if history had never descended upon them, taloned and screaming.

Coming closer to the entrance of the 9/11 Memorial, ticket in hand, History returned with a stern face as we circled through a maze of security checkpoints and metal detectors. The Memorial itself remained out of view, shielded from our eyes by banners stretched over the fencing. When we hustled into the site, we saw a large plaza checkered by hundreds of young trees, oaks I think, planted in strips of grass, running in lines around the twin fountains which rest on the footprint of the Towers. We could hear the fountains. We watched the crowds flowing towards their light.

Coming closer to the entrance of the 9/11 Memorial, ticket in hand, History returned with a stern face as we circled through a maze of security checkpoints and metal detectors. The Memorial itself remained out of view, shielded from our eyes by banners stretched over the fencing. When we hustled into the site, we saw a large plaza checkered by hundreds of young trees, oaks I think, planted in strips of grass, running in lines around the twin fountains which rest on the footprint of the Towers. We could hear the fountains. We watched the crowds flowing towards their light.

This is not what I expected. Families with young children in strollers pushed toward the water, couples meandered arm in arm, and extended families, perhaps in town for the holidays, grouped together, smiling, for photos. No one was shouting or running, but neither is this a somber place, an arena of pure reflection, like the Vietnam Memorial.

At the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C, a visitor walks along a sheltered, straight line of space and further limits that space by turning inward, toward the black polished granite that carries the names of the dead. He reads the names, drops his eyes to the gifts and mementos left by loved ones, and may look at the images of other visitors in the reflective granite. A person’s grief is acknowledged and may be witnessed but privately. Somehow, it reminds me of the atmosphere set off by the ritual of old-school Catholic Confession. While we waited to enter the wooden confessional booths, we turned inward and silently meditated on our sins, the potential death of our souls, on our moral history and on the possibility of repentance. When we slowly edge along the Wall, we turn inward and silently meditate on the dead, on our nation’s history and on the possibility of healing. Both are places of solemnity and silence.

At the 9/11 Memorial, we immediately enter a space where our eyes are not fixed but encouraged to roam, up towards the new buildings, around the skyline, towards the fountains, among other visitors. When those trees reach maturity, their canopy will cover much of the plaza in shade. There will be bird song. This will become a place of rest and an escape from the heat and blaring intrusion of the city. The fountains will remain open to the air, the trees are planted too far away to cover their expanse, but their flowing water will always draw visitors to them. Melville understood this 161 years ago in Moby Dick when he described “the crowds of water gazers” circling New York’s Battery on Sundays and where he came to understand that “meditation and water are wedded forever.”*

With everyone else, we walk toward the fountains. Surrounded by chest level granite caps that frame all four sides of the fountains’ rectangles, the names of the victims of the Twin Towers attack are carved into the caps all the way through.

We looked into the names which are traced in reflected light rising from the long troughs of water below the caps. I whispered a few of the names aloud, the rhythm provided by the three parts of each name. In doing so, the names seem to carry more auditory weight, as if I could create a wisp of their human presence through syllables and sound — Michael Scott Carlo, Charles William Garbarini of Ladder 61, Catherine Patricia Salter. The names become incantations. I saw one man gazing down at the cap and wiping tears from his face.

The water in the fountains floated in mist and fell in four waterfalls and rose in spray when the wind dipped into them. Their design emphasizes dynamism, movement, flow, all the confirmations of renewal. Lines of water and light scattered and flew back and forth across the surface of the falls. They are beautiful, the fountains are beautiful; they change us when we pause to gaze into them. When we found our way out and back to the street, we were grinning and happy. The smoking, stinking ruins once heaped here have been superseded by a landscape that promises life now and more life to come. Stepping toward traffic again, we hailed a taxi to take us to the West Village, and the cab driver, a man in his late 50’s, appearing confused, told us in hesitant, stumbling English that he was a Bangladeshi, but he waved us inside and dropped us off safely. When I paid him, he looked at me with a big smile and said, “You are my first fare.” I could have levitated with happiness.

(Looking South from the 85th Floor Observatory)

Late that night we paid to rocket up to and then walk about the Empire State Building’s Observatory, 85 floors and 1050 feet above the city. The streets seemed like flow charts delineating the passage of many-colored atoms, billions of atoms flashing and surging, emitting lights and siren sounds and horn blasts. We easily tracked fire engines, police cars, taxis and ambulances, the four most intense emissaries of atomic movement. Bright dots of planes and helicopters seemed permanently suspended above and even with us.

I love this city. The twin schizophrenic poles of my deepest attractions oscillate between Yellowstone and New York, between the Park’s raw wilderness and New York’s overflow of millions of people and their accompanying, civilizing gifts.

North, south, east and west, the staggering complexity of this city seemed to open up in layer after unfolding layer as if man, the sorcerer king, had finally discovered the core of his genius – the construction of life itself out of steel and glass, concrete and plastic, neon and motors. Everywhere, in the companionable strangers looking out and over the brilliant grids, and in the vast vibrating spaces all around us, the life force itself, electricity, pulsed in seams and veins. All of us gathered high above seemed to have internalized that force, and we carried it with us when we left the building and entered the atomic flow of the streets.

*Herman Melville, Moby Dick, Chapter One, Loomings