As a student-teacher I taught my first class ever with my fly all the way down and my white-haired, very proper supervising professor signaling from the back of the classroom, her charm bracelets making metallic crinkling noises as she waved. Thoroughly gob smacked by the ninth graders responding to me as if I were brilliant, I had entered a fool’s-dream. I thought she was offering encouragement.

As a student-teacher I taught my first class ever with my fly all the way down and my white-haired, very proper supervising professor signaling from the back of the classroom, her charm bracelets making metallic crinkling noises as she waved. Thoroughly gob smacked by the ninth graders responding to me as if I were brilliant, I had entered a fool’s-dream. I thought she was offering encouragement.

For my second interview at one school district, I was summoned into an enormous, darkened office, the drapes drawn against a harsh afternoon sun. I was offered a seat at the edge of a group of men in suits who formed an upside down U. Sitting stiff-backed and empty-handed, I was isolated at the bottom of the U. There must have been a dozen seated men all looking at me as if I had dragged something foul in behind me. The sharp questions came randomly, from all sides of the U, so that I had to keep turning my head to find the questioner against the dark background. When I walked out into the hot July light, I felt as if I had been tested for entrance into a sinister band, a society of hawk-eyed ominous suit-men, and that those sharp-voiced men sitting in the gloom would decide my future. They did. The next day one of them called and offered me the job teaching in the Chester County High School where I remained for 36 years. I could not have been more surprised.

In September of 1975 I began my career. On my third day of teaching, a last period on a Friday, I sprinted down a hallway to the back of the school, and in front of a hundred witnesses I thumped a boy against a brick wall — I had caught him whacking another in the head and balls. Throttling him, I shouted that I would “tear his m*********ing throat out and make him m*********ing eat it” if I ever saw him doing so again.

The HS was out of control – at passing times the narrow hallways stood shoulder-to-shoulder with pushing students, loud as a wild rally in a city square; fights between big, long-haired flannel-shirted farm boys broke out three or four times a week; the bathrooms were jammed with smokers, and a smoking area outside was awash with the stench of whisky and weed; jammed to overflowing classes surged to 35 and over 40; the intimidating scene of Hick Row loomed at the very edge of the parking lot, balanced above a steep hill – a line of 25 or 30 mud-covered pickup trucks, all of them parked hood out towards the main entrance, scoped Remington and Winchester hunting rifles resting in gun racks by the rear windows. I came to the HS just as the toxic elements of the late sixties arrived — the drug culture and a pervasive disrespect for authority. And our Principal, a nice enough guy who looked as if he was in a state of a perpetual nervous breakdown, was completely frozen by all of it. Each April he gave his ‘Let’s keep a lid on it” speech to an incredulous faculty. That was his only answer to the turmoil. His career in Chester County ended when seniors threw tennis balls at school board members and the Superintendent during HS graduation ceremonies; a few days later he stuffed mailboxes with numerical evaluations of teachers that were so irrational the Superintendent erased every one.

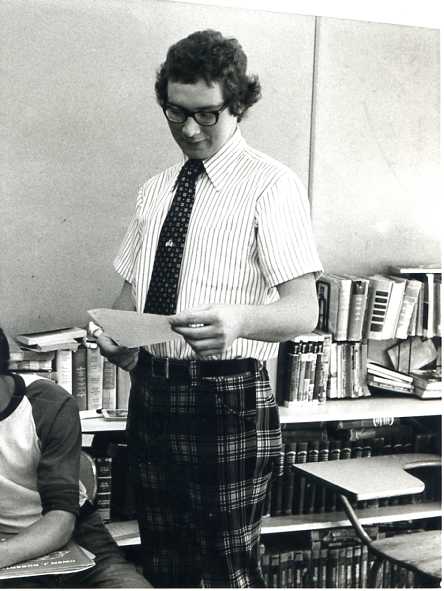

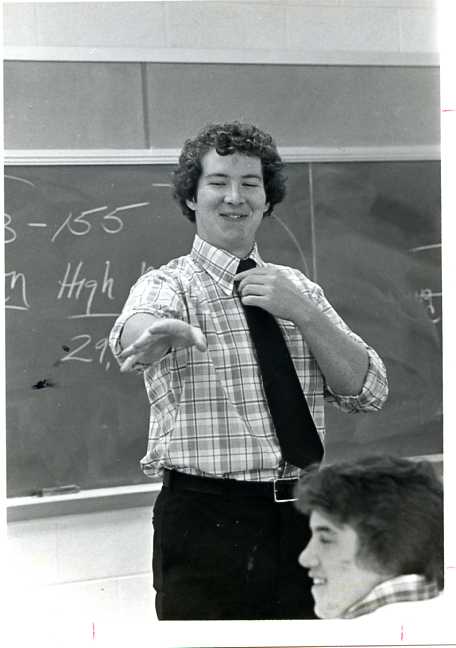

I did not know what I was doing. I arrived early each morning looking like a twelve year old who had been caught behind the barn and given an epically bad haircut by the kind of mammoth-boys who now filled my classroom. I wore polyester everything in unmatched patterns. God help me, I wore clip-on ties. My heavy, black glasses looked as if they required a crane to fit onto my thin, freckled face. I can now see that I had tumbled into a stage production designed by Darwin: everyone in the classroom is watching you; let’s see how you survive this — amiable tough guys, who you liked, bring booze-splashed drunks to your classroom and ask you to let them sleep it off in a back row. Or this – a budding 20 year old sociopath named Jack, the size of Jabba the Hutt*, sitting right in front of you, third row first seat, spends fifteen minutes methodically dismembering a fly he had snatched from the air and meticulously arranging the pieces in straight lines with a sharp pencil point. Or this — in the midst of a lesson, M80’s blow up a toilet next to your room. Or this – your kids are quiet and writing and you are breathing easily, and then screams and curses and crashing lockers ring out in the hallway; when you slam open your door, you see three army-jacketed girls hammering another girl, tufts of her hair already in their hands.

I survived because I was more terrified of failing than I was of anything that happened in school. Someone would have had to kill me to get me out of that building. I could not imagine going home to my mother and father, my father especially, and saying, “I just could not take it.” I could not have borne the disappointment that would have come into his eyes. I grew tougher.

I survived because many faculty members were superb. The best ones preserved the thin line between complete chaos and a jagged equilibrium that allowed the days to pass in a semblance of order. Many were in their late thirties and early forties; they were veterans who liked each other. They were generous with their time and advice, the best collective combination I have ever experienced of fortitude and unmatched teaching skills, and they were electrically alive. They were joyous and disorderly and rebellious and unafraid and no group has ever made me laugh harder and longer. I survived because I loved coming to work with them.

I survived because I watched them all the time and learned from them. I discovered that you can hold kids to attention with your voice and eyes alone, and that they will stay with you if you can find ways to show them that how you love your job encloses them at the center of that love. They taught me how to teach writing and how to write myself – cut BS, value clarity and precision above all, and allow the writer to find his or her own voice. They showed me that if you can make kids laugh, you can ask them to do anything. I discovered my father’s craft inside me — I learned how to tell stories. I found that if you steadily stared right into the eyes of the toughest boy, without speaking, that he would shy away from a confrontation. I saw a big man, a good man, the best human being in the school, tell a student that he was sorry if he had done something to hurt him, and beginning with that moment, I located the second half of a fundamental paradox that became a centerpiece of my teaching persona: apologize to your students if you let them down. Let them see that you make mistakes. At the same time, make sure they know that you will never back down from a fight. The best teachers in the school, male and female, loved their students and took no s***it.

I survived because I created a mask that I had never worn before. I could not allow myself to ‘lose face’ with high school students; that is the term I used. I think I picked it up from a Toshiro Mifune** movie. Here I was, a milky-faced stick man in rural Pennsylvania imagining myself as a Samauri. How weird we can become! I adopted this Japanese code — I would never allow myself to be humiliated. Thus I threw myself at hallway fights, howling and grabbing hair, arms, throats, legs. Once I blocked a hallway to bands of wild juniors and seniors who had started a roving, unruly sit-in to protest rules meant to regulate the smoking area. I planted myself in the middle and bellowed that I would fight the first SOB who crossed the line where I stood. They stared at me as if I were a maniac who had just dropped out of the ceiling on top of them. Then they turned around and walked back down the way they had come. I had achieved my inner-crazy person. I was lucky on more than one occasion that I did not have my teeth picked off the floor and handed back to me.

That first year I prepared for nine classes – the English curriculum had adopted a Quarter Course system in a desperate attempt to interest disaffected students. Every nine weeks we shifted all five classes. We met all new students, grades 9 through twelve mixed together. We often had to switch to new courses. I lowered my head to my work in September and did not raise it until June. Exhausted, I came home from school to a tiny basement apartment and collapsed into my second-hand bed for one or two hours of unconsciousness, shoes still on, not even my shirt unbuttoned. Then I ate a thrown together bachelor meal and began planning lessons and grading essays until late in the evening. I worked most of the daylight hours of Saturday and Sunday as well. I had to teach myself how to teach. I would not walk into a classroom unprepared; I imagined and feared the empty moment — my face slowly coming up to all those eyes, some beginning to already darken with a predatory gleam. I would not fail.

I felt under constant pressure to keep order, to reach every boy and girl, to learn everything at once. I struggled how to learn to read a class by adjusting the filters on the torrents of information that engulfed me each class period. I struggled to summon energy from unknown reserves. I adapted so as to become performer, counselor, cop, expert, and cheerleader. I made mistake after mistake after mistake. Students forgave me. Administrators forgave me. I burned through second chances. The year sometimes felt as if I were crossing a dangerous wilderness river, balancing my cumbersome pack, the unseen stones slippery and unsteady beneath my feet, trying not to think about the far shore, watching for surging logs, conscious of the cold penetrating my chest.

I survived because I learned to value the days. I remember one day when I figured out that I had gone past a threshold and was no longer an imposter or stranger in this High School. Sometime in the late Spring I arrived very early. Everything was quiet. I entered my classroom and threw open the enormous windows and took in the aromas of cut grass and of the big trees in the courtyard. I remember turning to look at the chalk boards and at all the rows and at my desk. I had slipped into this career. I was only looking to pay the bills, and instead, by the purest, most bone-headed luck, I had chanced upon a ravishing, exhilarating, arduous, maddening routine. Someone was going to pay me to work with children and read books! I had a place to come to every September through June that felt perfect! I had become a partner in a vital, perpetually evolving community! This was more than survival. This was a new life.

All of this happened in my first year as a teacher.

*Jabba the Hutt: http://www.mwctoys.com/REVIEW_022107a.htm

**Toshiro Mifune: http://www.criterion.com/explore/157-toshiro-mifune

Loved the pictures.. it is fun to look back a little.

Bravo on a wonderful article! You have triggered so many similar memories for me.

I would have loved to be a mouse in a tiny corner of your classroom!

I forgot how curly your hair was. Love the ”Charlie Pants” Amazing how fast those years went.

This was fascinating and touching to read. Not only because it brought back memories of my favorite and the single most important teacher in my education career, but as someone entering the secondary OJR school system in 1981 at the tail end of this chaos, I have vivid memories of much of what was mentioned.

Thank you for this.

HA! I remember our fights, and I totally would have called you out on your zipper being down! Thanks for helping me through a hard time and for helping to shape the better person I am today 🙂