Helen Macdonald plays games with her goshawk. She snaps a book closed. Her hawk, Mabel, “makes a curious, bewitching movement.” Macdonald, intrigued, tears off a strip of paper, “scrunches it into a ball, and offers it to the hawk with [her] fingers. She grabs it with her beak. It crunches. She likes the sound. She crunches it again and then lets it drop, turning her head upside down as it hits the floor.” Her beak is pointed at the ceiling. Macdonald has seen this behavior before in fledglings at play. She picks up the paper and offers it to her again: “She grabs it and bites it very gently over and over again: gnam gnam gnam. … Her eyes are narrowed in bird laughter.” Macdonald “ rolls a magazine into a tube and peers at her through it as if it were a telescope. [Mabel] ducks her head to look at me through the hole. She push[s] her beak into it as far as it will go, biting the empty air inside. … She pulls her beak free. … She shakes her tail rapidly from side to side and shivers with happiness (113).”

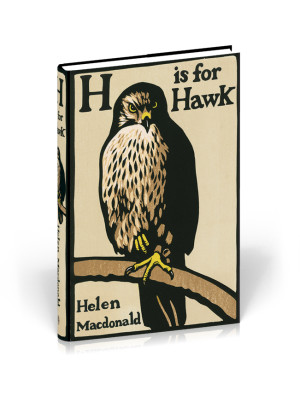

The book does not begin with play but with death. Helen Macdonald’s father dies suddenly and way too early, and her entire life reels back and then apart in shock and grief. He had made his living as a photographer, and he had taught her how to be patient and how to watch, how to wait for what might come and while waiting, how to settle and take in everything she saw. A falconer, someone who had kept a kestrel before, now in the center of blind devastation, she determines to adopt a goshawk, an intensely difficult bird to train to the glove. The book describes her despair, her experiences with Mabel, her gradual recovery of her clear mind and health, and it also tells the story of T.H. White, author of the greatest of the Merlin/King Arthur novels, The Once and Future King, and his own travails which led him to attempt to train a goshawk.

Her anger at her loss “was vast and came out of nowhere. … Rage crouched inside [her], and anything could provoke it.” But she perseveres with Mabel and keeps “notes in impersonal shorthand, detailing the weather, Mabel’s behavior, measurements of weight and wind and food (140-141).” She sees that “every tiny part of her was boiling with life.” She tries to move into Mabel’s “present only, and that [became] my refuge — My flight from death was on her barred and beating wings (160).”

Once, in a comparable moment in life, having entombed myself in work, and living in an empty house surrounded by woods and fields, away from the road and walkers and casual connections, I went a little mad with loneliness and a wild desolation kept alive by memories of one who had lived and died there. On weekends and after school, as spring swept in against my cindered heart, unable to think, unable to remain still, I roamed outside like a shadow, bereft of control, and so emptied that out of a simple reflex of noticing anything that moved, I began to watch birds so closely that I could tell from their flight paths where their nests might be. I began to keep an inner catalog of nesting spots. Day by week, as spring eased into summer, and then during hay cutting times and then into high summer when the wild flower meadow we had planted came into full glory, I walked those same woods and fields and found nestlings and scared away cats, and in the fall I made a map of every nest. Year by year until I left, I kept that map current. Birds did not save me, but their immersive presence helped skirr me out of my brooding. The surfaces of their world, utterly removed from my sadness, gave me other lives over which to skim and be knit together again in the act of moving and looking.

Once, in a comparable moment in life, having entombed myself in work, and living in an empty house surrounded by woods and fields, away from the road and walkers and casual connections, I went a little mad with loneliness and a wild desolation kept alive by memories of one who had lived and died there. On weekends and after school, as spring swept in against my cindered heart, unable to think, unable to remain still, I roamed outside like a shadow, bereft of control, and so emptied that out of a simple reflex of noticing anything that moved, I began to watch birds so closely that I could tell from their flight paths where their nests might be. I began to keep an inner catalog of nesting spots. Day by week, as spring eased into summer, and then during hay cutting times and then into high summer when the wild flower meadow we had planted came into full glory, I walked those same woods and fields and found nestlings and scared away cats, and in the fall I made a map of every nest. Year by year until I left, I kept that map current. Birds did not save me, but their immersive presence helped skirr me out of my brooding. The surfaces of their world, utterly removed from my sadness, gave me other lives over which to skim and be knit together again in the act of moving and looking.

This is the best memoir I have ever read and the best book on those personal kinships we create with the natural world. If you spend time out of doors, if you love birds, if you love evocative, sharp writing, if grief has ever darkened you and then you found your way out and into light again, then buy this book. You will find yourself reading it slowly, rereading pages, reading it aloud, and turning down corners because you will wish to find those passages again.

This is the best memoir I have ever read and the best book on those personal kinships we create with the natural world. If you spend time out of doors, if you love birds, if you love evocative, sharp writing, if grief has ever darkened you and then you found your way out and into light again, then buy this book. You will find yourself reading it slowly, rereading pages, reading it aloud, and turning down corners because you will wish to find those passages again.

This has been on my list for some time! I love the description of the hawk’s playfulness. It seems whenever you stop long enough to really look at something, you will find its soul.

It looks like I am exactly a year behind you in my reading. What other gems have you read since that I have missed?