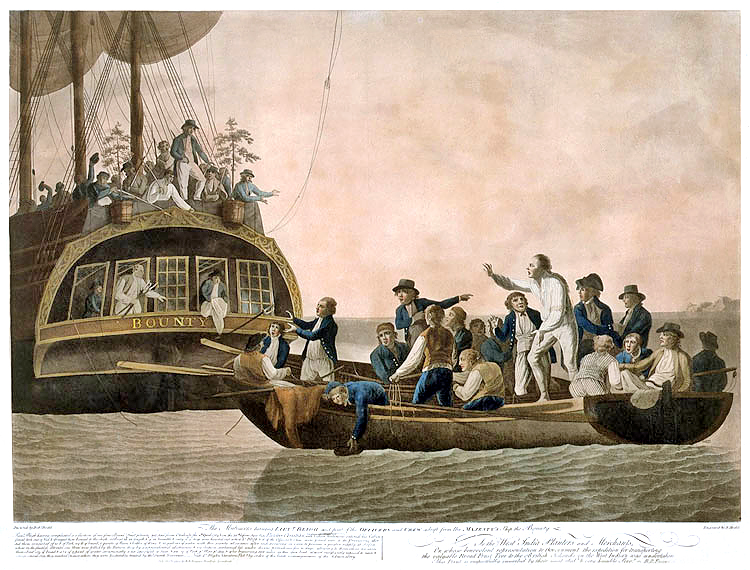

Beginning in April of 1789, William Bligh sailed over 3600 miles in a 23 foot cutter. Eighteen men from the Bounty, cast off by Fletcher Christian, accompanied him. At its center the boat was six feet wide and was overloaded; seven inches of freeboard separated them from being swamped. They endured terrible storms, enormous waves, chilling sea-cold nights, a relentless sun, hunger, thirst, boils. Forty eight days later they arrived in Timor in what is now Indonesia. He brought seventeen men alive to that shore. One man had been killed by natives on a island where they had stopped to reprovision. Bligh kept discipline and reinforced morale. He rationed food and water. He kept watch, navigated and baled continuously with the others. If he despaired, he never revealed it.*

Beginning in April of 1789, William Bligh sailed over 3600 miles in a 23 foot cutter. Eighteen men from the Bounty, cast off by Fletcher Christian, accompanied him. At its center the boat was six feet wide and was overloaded; seven inches of freeboard separated them from being swamped. They endured terrible storms, enormous waves, chilling sea-cold nights, a relentless sun, hunger, thirst, boils. Forty eight days later they arrived in Timor in what is now Indonesia. He brought seventeen men alive to that shore. One man had been killed by natives on a island where they had stopped to reprovision. Bligh kept discipline and reinforced morale. He rationed food and water. He kept watch, navigated and baled continuously with the others. If he despaired, he never revealed it.*

He kept a log. He later wrote letters and a narrative of the mutiny and his journey. He served in the Royal Navy for many years, performed heroically in battle with Nelson during the Napoleonic wars and was known as a captain who used the lash infrequently. We know his official positions. We know of his courage, temperament and skill as a naval officer, but he came from an age and a race who were generally not inward looking. In our confessional age, our epoch of memoirs, he is opaque. He never tells the reader how he changed or what he learned.

The nature of a journey is to reveal, or so we who are economically snug have come to believe. We have enough to eat, a safe bed, 401k’s, a warm house, and some have the security of rule by law. Many Americans have the extravagant gift of being able to traverse time and distance only because we are curious, and in this country, three million miles of roads on which to wander.

A journey tries to move in one direction. By the hour and day, in synch with time, we move away from the locale of the previous day and into a type of continuous present. The trail or road ripens before us, the sea parts, or from above the patterned land clips by, our eyes switching focal points at speed. What comes next we think. What will drop into our fortunate, open, airy lives?

A journey tries to move in one direction. By the hour and day, in synch with time, we move away from the locale of the previous day and into a type of continuous present. The trail or road ripens before us, the sea parts, or from above the patterned land clips by, our eyes switching focal points at speed. What comes next we think. What will drop into our fortunate, open, airy lives?

Entering Tarbert Harbor in July, 1976

Yet as we travel we also move in the dimensions of memory and appetite. If we are returning to a city or mountain, river or ocean, we notice the changes — richer or suffering, more developed, cleaner, more tawdry or as shiny as silver foil and as thin in soul? We covet — this landscape, that vista, these crowds out of which emerges an evening’s pleasant acquaintance; this street, this house that could be a new home if only….

We experience reverie or regret or both simultaneously. What life might I have made here? If I took the jump now, am I strong enough to reach the other side? Or more wistfully, maybe we simply speak in a refrain: “I should have…. I might have….”

Bruce Chatwin believed that human beings evolved in concert with our need to keep moving and to create as we move, a hypothesis made more curious in this decade of the virtual journeys enabled by the web, movies, games and tv. All but one of the children I tutor spend their days in this kind of travel — from car or bus to school, from school to their room, in their room to the screened worlds. This terrifies me. They are always under control or believe that they are in control. Do they even make deep memories? They seem engaged in building tiny, packaged lives.

I spent thirty-six years in rooms the size of a large garage, and while I was almost always thrilled by my work, I was always grateful for a view, and for big windows. In free moments I could look out those windows, out of the bunker-rooms, and drift. During all that time, I never stopped imagining other personas of myself, doppelgangers, somewhere in Idaho or Montana, Manhattan when it was affordable, Sarajevo or Iraq, or Galway perhaps — all these alternative me’s walking into their mornings as soldiers or doctors or policemen.

Once we leave home for any faraway place, do we ever stop imagining faraway lives? If travel teaches us anything, it is that the unexpected event, if only in retrospect, should be cherished because it shook us out of our insular dream-lives.

It does not take long for that dreaminess to curdle and become sour. One must have work. One must make a purpose. Along the edges of that purposeful, adult life however, for some of us, this urge to be going never goes away.

The memories of travel that come unbidden and give color and perspective to how we live now — those seem most valuable.

When I first understood how deeply strange the lands outside my little packaged life could be, I was 23, leaning on the rail of a ferry that was coming into Tarbert on the Isle of Harris on the Outer Hebrides. Dangerous, low clouds seemed to labor only a few hundred feet above the town. A cold wind dropped down with them and struck our faces. No one else on earth except my traveling friend knew where we were. We were heading off into the hills above the town.

When I first understood how deeply strange the lands outside my little packaged life could be, I was 23, leaning on the rail of a ferry that was coming into Tarbert on the Isle of Harris on the Outer Hebrides. Dangerous, low clouds seemed to labor only a few hundred feet above the town. A cold wind dropped down with them and struck our faces. No one else on earth except my traveling friend knew where we were. We were heading off into the hills above the town.

Upon landing, we struggled to understand the thick Hebridean accents. We had nothing booked, no place to stay. We shouldered our packs and walked out on the road and kept walking in a cold rain, our thumbs stretched out of our ponchos and waving at the few cars that drove past.

In a valley as beautifully desolate as any I have ever seen, we found a bed and breakfast and used it as our base for two days — a refuge where we could eat and talk by a peat fire and warm ourselves.

A mile or so away, standing alone in another valley, was a pub — a small, stone, whitewashed building. Standing before its front door, I could turn in a circle and see nothing but hills covered in heather, slow moving sheep high up, and mist, everywhere mist and not one tree or bush anywhere.

It was dark inside. Everyone turned to look at us. We took our pints and sat at a wooden table in a corner, but we were out of the ordinary, Americans in an off-the-track place that saw few of us, and soon we were talking and laughing with men whose hands I remember. They were huge, big-knuckled things; their pint mugs disappeared inside them.

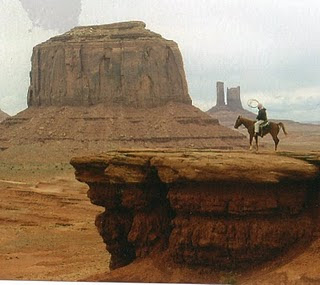

The more beer we drank, the better we could understand their accents … or something like that. We ended up finally talking about John Wayne and cowboys. I think these men all imagined America as an immense Monument Valley broken up here and there by cities, and that all of us owned horses and that we spent our free time riding across endless western plains.

The more beer we drank, the better we could understand their accents … or something like that. We ended up finally talking about John Wayne and cowboys. I think these men all imagined America as an immense Monument Valley broken up here and there by cities, and that all of us owned horses and that we spent our free time riding across endless western plains.

This photo gives you an idea of the Hebrides landscape

At closing time, the pub emptied and we walked out into a bright dusk — in July, at roughly the 57th parallel north, we had about 17 hours of daylight. My friend started climbing the road over into the next valley, but I had to piss and as there had been no indoor bathroom, all of us stood next to a broken wall and relieved ourselves. An enormous man in wellingtons and coveralls bulled in next to me. He towered above me. His white t-shirt bulged at the neck, shoulders and arms. He looked like a Viking throwback, his hair shaggy and almost a platinum blond.

I finished, said my goodbyes and turned to follow my friend back to our B and B. I could see him vanishing over the rise. The Viking stepped in front of me. He stood very close. He said, “I want you to do something for me.” He smiled. I had to bend my neck to look up at him.

“Sure,” I said, “What would you like?”

“I want to go to America,” he said, “but I dunna think I’ll ever get there so I want something from America. Please, if you would, when you go home to Oklahoma, buy me a pony, a big pony like the Indians rode.”

He smiled at me as if this were really possible, as if I could pull this off, as if I could make a pony appear so that he could ride it up and down these Scottish valleys in a big John Wayne cowboy hat.

He smiled at me as if this were really possible, as if I could pull this off, as if I could make a pony appear so that he could ride it up and down these Scottish valleys in a big John Wayne cowboy hat.

“I don’t know how I could get it here,” I said.

“Acchh,” he said, “that’s easy. Mail it to me.” He pulled a piece of paper out of his pocket and a stub of pencil and scrawled an address on it and with both meat-hook hands folded in into my palm.

“Thank you”, he said, ‘Thank you,” and he turned and walked away. We left early the next morning. I have never been back.

I still think of him, and I am sorry, sincerely so, that I could not mail him his pony. I would give a great deal to have watched him wear a big white hat on his huge head and ride a little Indian Paint into the mist and to have seen his grand smile again.

Source The Bounty by Caroline Alexander

This brought back so many memories–of me, Rosemary and Erin when we were in Scotland and England the summer after Erin graduated from High School. Memories of the 3 of us just getting on a boat and going to Ireland with no reservations or plans. Rosemary and I cried when we first stepped on Irish soil–Erin just tried to distance herself from us–embarrassed! We also did the same thing in Wales. We just got on a train and picked a stop at random to get off. I have such great memories of spending that time with my sister and daughter.