All great painters do this, I think, but right now I am in love with O’Keefe who I hear in my imagination telling me, “Here is one more way to see.” For her, form and color are everything. Not the thing itself as denoted by name – mesa, cottonwood, stars, clouds, courtyard, apple, plain, flower – but the solidity, shape, arrangement and hues of what she watches and then paints. She finds the tensile drama of a vista or a thing and evading language, she creates what she felt in what she saw, and she is so good at this, that in looking at her paintings and at the landscape of New Mexico, I become a kind of emotional circuit between the three, the painting in front of me, the images I carry in my memory and the emotions they provoked in me — those of awe, inspiration, and a sense that I have witnessed something sublime, a transcendence of a kind I have rarely experienced. Lewis Mumford described her work as “[possessing] that mysterious force, that hold upon the hidden soul, which distinguishes important communication from the casual reports of the soul.”*

All great painters do this, I think, but right now I am in love with O’Keefe who I hear in my imagination telling me, “Here is one more way to see.” For her, form and color are everything. Not the thing itself as denoted by name – mesa, cottonwood, stars, clouds, courtyard, apple, plain, flower – but the solidity, shape, arrangement and hues of what she watches and then paints. She finds the tensile drama of a vista or a thing and evading language, she creates what she felt in what she saw, and she is so good at this, that in looking at her paintings and at the landscape of New Mexico, I become a kind of emotional circuit between the three, the painting in front of me, the images I carry in my memory and the emotions they provoked in me — those of awe, inspiration, and a sense that I have witnessed something sublime, a transcendence of a kind I have rarely experienced. Lewis Mumford described her work as “[possessing] that mysterious force, that hold upon the hidden soul, which distinguishes important communication from the casual reports of the soul.”*

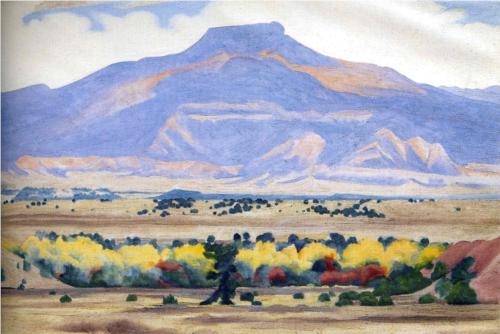

Pedernal, 1941 (“In old age she joked, ”’It’s my private mountain. It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it (295).”)**

Pedernal, 1941 (“In old age she joked, ”’It’s my private mountain. It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it (295).”)**

In New Mexico, I felt something fracture apart for me – God, doesn’t that sound ridiculous, even pompous. Yet, I cannot get beyond that word “something.” I cannot come close enough to what I felt. As much as I care for language, it gets in the way of trying to capture the reality of this experience – it becomes a gauzy curtain between what I know and knew and my ability to explain that knowledge.

O’Keefe breaks though that curtain because she sidesteps language. Her eye sees, mixes colors, arranges shapes within a visual frame and then makes a version of what she sees — all without a noun or a verb.

She understood that what she painted had to be kept new and that neither the eye nor the mind ever settles down. She wrote to Sherwood Anderson, the American writer: “Making your unknown known is the important thing – and keeping the unknown always beyond you – catching [and] crystalizing your simpler clearer vision of life – that you must always keep working to grasp (210).”**

Her biographer writes that for her “pigment … was trustworthy yet unexplored terrain in which new tonal variations were still to be mined. … She used to tell frustrated interviewers that she didn’t like to think in words, that words were ‘inelastic’. … Placing lines, masses, symbols and colors together so they spoke eloquently — this was her natural idiom (352-353).”**

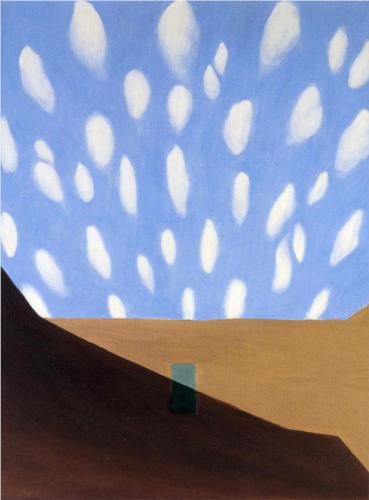

The Lawrence Tree, 1929 (“Over the years she used to sleep on the roof [of one of her homes] in a sleeping bag in order to awaken under the vast multitude of desert stars, to watch the pale, cold moon on the cliffs, and to see the first morning light touch what she called ‘”my wonderful world (297).'”)**

In New Mexico, Georgia O’Keefe found her best home. Quoting D. H. Lawrence, she wrote that each day there was as clear to her as “the loud ring of a hammer striking something hard.… In the magnificent fierce morning of New Mexico one sprang awake, a new part of the soul woke up suddenly (225-226).”

I have had six or seven experiences that were similar in their impact to first seeing this New Mexico landscape, each lasting a few minutes, no more than that, where what had been impermeable loosened its braced enclosures and another seam of the world shone through.

On one occasion, alone in a sodden field in the English midlands when a lone oak tree seemed to catch fire in front of me; on a night climb in the San Juan mountains of southern Colorado when great winding sprays of the Milky Way threw shadows upon the snow; in college with two girls, sober as a priest, I swear, when I felt as if I had won all the golden powers of speech; a handful of charged moments in the classroom, and once under tragic circumstances when I abruptly understood how courage can be wordlessly passed from one person to another. And here, under this sky, in this place so strange in contrast to Pennsylvania, I had been walloped yet again.

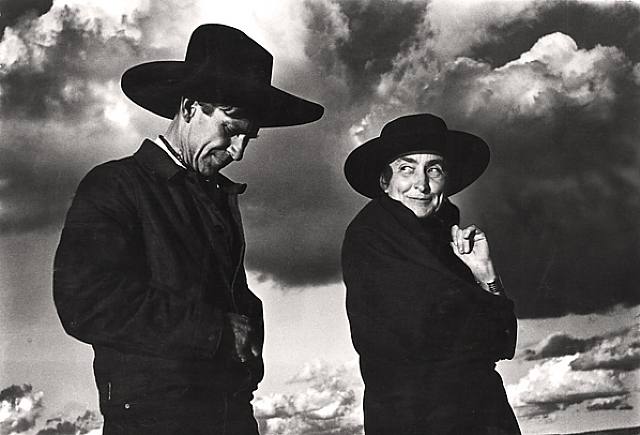

O’Keefe could be very difficult. She kept a series of Chows that she never trained and that once bit a mother who was trying to protect her child from them. She refused to learn Spanish, a rebuke that seems terribly impolite considering the location of her final homes and of their many workers without whom she would never have had the hours to paint. It made her aloof from her neighbors and almost certainly shut her out of warm friendships. Too often, she let her sharp, abrasive tongue loose on those who did not deserve its blade. But she was also generous, especially to the village of Abiquiu, kind in equal measure to friends and children, and utterly devoted to her painting, and I know from experience how such zeal can leave others out of one’s concentration.

Black Hollyhock, Blue Larkspur, 1930

She took artistic and personal risks and paid the costs in loneliness, but she also “compared her existence to balancing on the thin, sharp blade of a knife where … it was worth a misstep if she was enjoying herself (436).”**

She died on March 6, 1986. She was 98.

She spoke of only one sorrow regarding her death: “I only regret that I will not be able to see this beautiful country anymore, unless the Indians are right, and my spirit will walk here after I’m gone (437).”**

*The New Yorker, January 18, 1936.

**Portrait of an Artist: A Biography of Georgia O’Keefe by Laurie Lisle

Cottonwood Tree in Spring, 1943

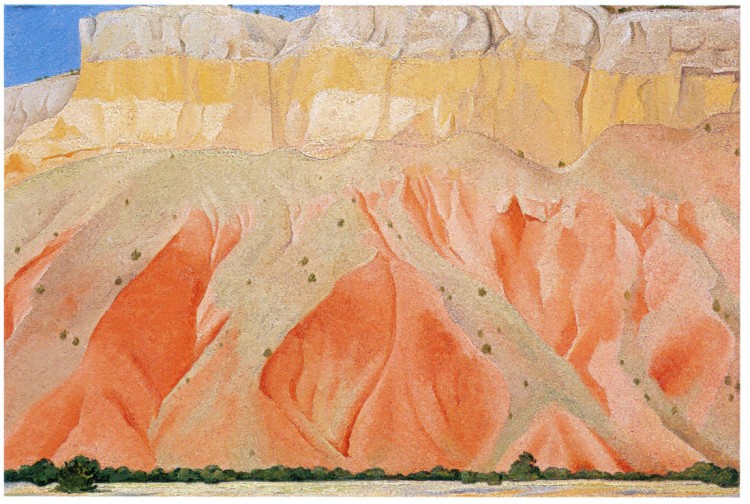

Red and Yellow Cliffs, 1940

Mike,

I love what you wrote about Georgia O’Keefe. Her work and life really moved me as well. Her paintings really do justice to New Mexico, but unless you’ve seen the high desert country, you would never know it.