Most Americans live lives almost wholly segregated by race. I am no different. I only want to understand what I have seen, what I now see, and what I think.

The first black person I saw looked ancient, an old, old man in a suit and fedora almost curved into a crescent over a cane and struggling up the steps to my neighbor’s porch on the outskirts of Myerstown, Pennsylvania, in the middle of nowhere, in 1955 0r 56. I was three, maybe four, and this image remains absolutely clear and soundless, as if I were watching the beginning of a play from a distance.

A Korean war orphan, adopted by a veteran who brought him home from that conflict, was the only non-white child in my first grade class and in all of my grammar school years at St. Gertrude’s and Sacred Heart. One young black man graduated with my high school class. I do not remember one person of Mexican or Hispanic origin from any of those years.

Race came into our home in the form of news and entertainment. When it did so, it had a black face. Since then, in large measure, the word has carried the images of black men and women.

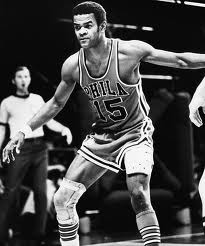

I became helpless with laughter when I listened to Bill Cosby records. I saw Stepin Fetchit dance with Shirley Temple, Tarzan and King Kong defeat African tribesmen, Woody Strode back up John Wayne in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence and Sammy Davis Junior sing and laugh at Frank Sinatra’s jokes. I admired Hal Greer and Bill Russell, professional basketball players, with something close to ferocity, and felt great delight each time Dick Allen came to bat for the Phillies in 1964. His capacity to volley balls over the roof of Connie Mack Stadium gave me a joyous buzz of anticipation. I did not understand why he later struggled with Philadelphia newspapers and why Phillies fans turned against him. The only definitive bigotry I knew of was directed against Catholics. I fought boys on the playground because of it. However, I drifted through a placid sea of casual racism directed against black people. I heard the N word used, always by men, often enough to leave memories. I do not remember it being attached to a sense of aggression. It was used as a statement of fact.

I became helpless with laughter when I listened to Bill Cosby records. I saw Stepin Fetchit dance with Shirley Temple, Tarzan and King Kong defeat African tribesmen, Woody Strode back up John Wayne in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence and Sammy Davis Junior sing and laugh at Frank Sinatra’s jokes. I admired Hal Greer and Bill Russell, professional basketball players, with something close to ferocity, and felt great delight each time Dick Allen came to bat for the Phillies in 1964. His capacity to volley balls over the roof of Connie Mack Stadium gave me a joyous buzz of anticipation. I did not understand why he later struggled with Philadelphia newspapers and why Phillies fans turned against him. The only definitive bigotry I knew of was directed against Catholics. I fought boys on the playground because of it. However, I drifted through a placid sea of casual racism directed against black people. I heard the N word used, always by men, often enough to leave memories. I do not remember it being attached to a sense of aggression. It was used as a statement of fact.

I look back now, and in a sensation that feels as if I were emerging from a deep sleep, physically disoriented and uncertain of what I understood, the subject of race took form in an historical and political context,  and the substance of that time makes the most sense now in a series of images and phrases that all flow together in a montage:

and the substance of that time makes the most sense now in a series of images and phrases that all flow together in a montage:

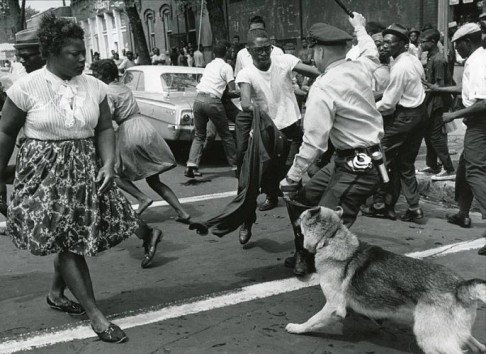

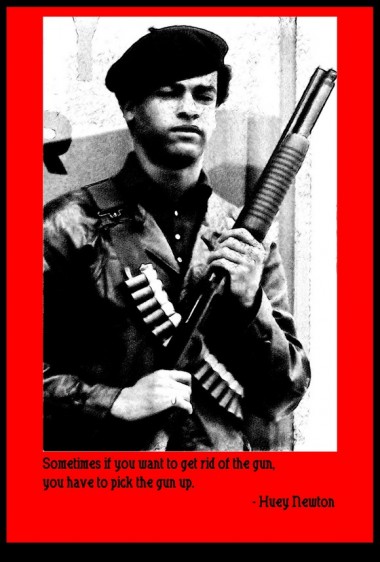

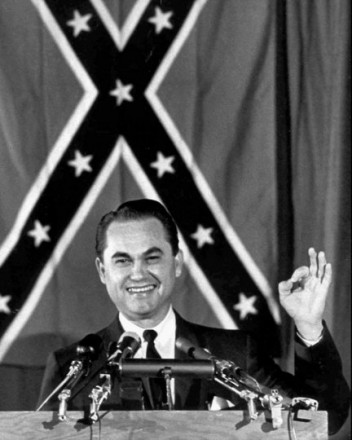

German Shepherds tearing into black men and women who are then tumbled along sidewalks and along store fronts by high pressure water hoses. Men and women being torn from their stools in a Five and Dime and being beaten by slick-haired teenagers in leather jackets. John Lewis, in Alabama, bleeding from head wounds. A burning bus on the side of a road. Two men raising their hands in fists and bowing their heads while standing on the winner’s platform at the 1968 Olympics. Watts and Detroit burning. Men, women and children carrying armloads of goods out of broken storefronts. National Guardsmen walking shoulder to shoulder down city streets, rifles extended, bayonets attached. Men standing on a motel balcony and pointing; a terrified scrum around Martin Luther King. Nixon’s Southern Strategy. Men in black berets and leather coats looking directly into the camera and balancing high powered rifles on their thighs.  Huey Newton promising to kill police officers (my father, a police officer). George Wallace, behind a podium, waving his fist up and down. Archie Bunker. Soul on Ice. The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Attica. An unremitting pall of smoke and a sense of fear that everything was coming apart and that rage had become the best and boldest coin of the realm, the conduit to manhood. #

Huey Newton promising to kill police officers (my father, a police officer). George Wallace, behind a podium, waving his fist up and down. Archie Bunker. Soul on Ice. The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Attica. An unremitting pall of smoke and a sense of fear that everything was coming apart and that rage had become the best and boldest coin of the realm, the conduit to manhood. #

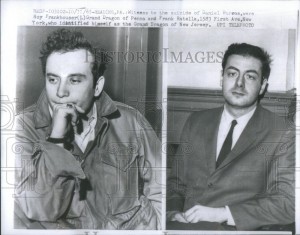

Sometime in the summer of 1970, I spoke with a man who wanted to exterminate or forcibly deport or imprison every one of color (and Jews). He became the white face of those who took conflicts and problems associated with race as the promise for violence. Roy Frankhouser Jr. was the Grand Dragon of the Pennsylvania KKK as well as the head of the State’s chapter of the American Nazi Party. He operated the ‘Mountain Church of Jesus Christ’, a row home in Reading whose first floor windows were covered by chicken wire and packed tight with sand bags. The cross on his sign was on fire.

He and another man, both wearing the same kind of dull brown uniform shirts buttoned to the neck and sporting stumpy ties and a belt or harness across their chests, both carrying American flags, were marching back and forth in front of the Quaker Meeting House in Reading on a sunny, warm Saturday morning. I had come with friends to listen to arrangements being made for a protest against the Vietnam War. He actually looked harmless — a ridiculous man in a get-up from a Marx Brothers film. I think that impression led me out to talk to him.

He and another man, both wearing the same kind of dull brown uniform shirts buttoned to the neck and sporting stumpy ties and a belt or harness across their chests, both carrying American flags, were marching back and forth in front of the Quaker Meeting House in Reading on a sunny, warm Saturday morning. I had come with friends to listen to arrangements being made for a protest against the Vietnam War. He actually looked harmless — a ridiculous man in a get-up from a Marx Brothers film. I think that impression led me out to talk to him.

Roy Frankhouser Jr., on the left, 1965

I might have expected a brute, but I got someone happy to talk, genial, and self-deprecating. I remember bits of the conversation. He claimed not to hate anyone. He claimed to love America and to be a Christian. He did not want race-mixing, that’s all, and he thought each race had its own purpose in life. He admired the Black Panthers. Now I can see his charming mask for what it was, a persona designed to seduce and deflect. His history was one of race hatred, violence, probably murder, certainly treachery, and a half-dozen other criminal enterprises including gun-running and money-laundering. He had perfected an art for the general public — he could “smile and smile and be a villain.”*

In September of 1970 I walked into my dorm room as a freshman and discovered that my new roommate had already arrived. His photos of himself with his mother and another with his little boy sat on the desk above his bed. My mother and father stopped moving behind me. They were staring at the photo of a young black man with an enormous afro. After a long silence, my father said, “He’ll probably paint a line down the center of the room and tell you to stay on your side.” When my parents left, I stood in the empty room, looked at his photographs and felt a complete blank inside. I had no idea what to expect.

Richard Montgomery, ‘Mo’, of West Philadelphia was my roommate for my freshman year. I was seated at my desk when he walked in, grinning. He too did a double-take. I saw his face close down, the grin vanish, and a wariness take its place. I stood up. He faced me. At the end of confused, hesitant movements, we shook hands. We did not spend time together outside the room. His friends were exclusively black, mine white, and both of us were on our own for the first time – there was so much to see and do – we both passed through all kinds of first time occasions and trials.

It took quiet weeks for us to begin talking. On many late nights only the two of us would be left awake, and we would sit in the silent dorm, one desk light turned on, and share stories, cautiously share anxieties, laugh together and stifle our laughter with pillows or shirts. The quiet was important, as if the room were a space apart from the pressures of trying to figure out who we were supposed to be.

His father was gone, his mother had raised him, and he spoke of her with both reverence and worry. He did not want to disappoint her. His boy’s name was Richard. He called him “my little man Mo”. He never used the word, but he expressed the concern – he was terrified that he would not be able to finish college, that he would fail. He had a quick mind, one with enormous potential.

He began to sink. For a semester he rode the whirlwind. He was good looking and had a sly, shy smile that appealed to women, and he was a nice guy with few sharp edges. He had the gift of attraction. But then he began smoking weed three or four times a day, drinking wine almost every night, sleeping until noon, cutting classes, falling behind in all his school work, and then he just stopped going to class. His eyes grew perpetually red-rimmed, and his skin seemed to shrink around his face and grow ashy and sickly. We talked less often, but when we did, I saw a young man in agony.

He did not know how to study. He seemed disoriented by the demands of his academic schedule, and yet too proud to ask for help. He knew that he was struggling, but he did not know how to fix what was wrong. College life overwhelmed him. Sometimes he talked about going back to Philly and becoming a utilities linesman, the one who climbed the poles and handled hot wire.

He had no respite off campus. The town was hostile territory, the shopkeepers sullen and abrupt in their dealings with black students, the townies actively hostile. Sometimes on Friday and Saturday nights drunken carloads of them would pass black students walking up to campus and bark out the Terrible word again and again, hyena-laughing and screaming.

Our talks stopped. I would not see him for days at a time. When I did, he gave me a nod with a half-smile and walked on with his group. I had my own trouble, having destroyed my first semester in a blaze of overindulgence in … everything my Catholic boyhood had never provided. I worked harder than I had ever worked in my life. In that way I was thankful for the solitude.

Maybe now I understand what happened. His high school had not prepared him for college. He walked out of West Philly into Indian Country, and initially he had been dazzled by the landscape and the richness of the experience, but he did not possess the survival tactics for an almost wholly white, isolated world. He let himself go deep into college pleasures, as had I, but I did not have to contend with the omnipresent awareness that I was … uncommon. My white skin let me fade into the mass. I could become invisible. Nobody minded my business, but I think he always felt white eyes upon him, measuring, dismissing, defensively preparing … and naming.

I think that the Names he was called on the town’s streets cut him to pieces. He only ever mentioned those incidents once. I do not think he spoke of them to me because he was enraged, embarrassed, at a loss for what to say. So he withdrew. He was nineteen, a decent kid, and maybe he did not have the academic grit to call upon when he struggled here, but he was also weather-beaten and adrift on a strange sea. I had received a good education before I left home, I had a father who expected me to do well, a home within easy reach, a dread of failing, and no one picked me out and called me that most vile Name and wanted to hurt me because of my appearance.

In late spring he was gone, his closet door open and empty, his photos missing. I saw his girlfriend the next day. He had withdrawn rather than fail. He went back home. I wrote him one letter. I never had a phone number. He never answered. I misplaced the address. I never saw him again, and the great flood of my life rolled over me, and I let him go.

Mo was the opposite of Roy Frankhouser Jr. who wore a mask to cover his ugly beliefs and cravings. I saw Mo without a mask, his dark skin becoming only that, skin alone and not a sign or symbol of anything else. I could not have articulated this at the time. I had not lived long enough to understand. Forty-four years later, I can see that Richard Montgomery changed my ideas about other human beings of color in this way — one by one, year by year, student by student, each African-American left the collective and become his or her name, an individual, a separate young man or woman. I am a sinner, too often nasty of mind, mouth and thought, susceptible to atavistic impulses and tribal prejudices, but Mo gave me a memory of a man whose fragile humanity became an immovable obstacle in the path of my own worst self.

I have to try to imagine what it would feel like to walk out of my house each day if I were a black man or woman. Aside from all the other normal anxieties and joys of the human condition, I think I would perpetually be aware of one question: which identities would be assigned to me that day? Like those videos that shuttle assorted faces at great speed, would I be perceived as a father, a mother, “welfare queen”**, athlete, “subhuman mongrel”***, overachiever, victim, predator, agreeable kid, “thug”, threat, church-goer, simply another guy, just another woman, maybe only as blessedly Normal?

I worry about those kids of color who I came to know in my classroom. I wonder whether they have grown the armor they will need to have a reasonably happy life — the translucent steel plates that will allow light to penetrate but which also ward off “the slings and arrows” of a hard world.

I come back to children again because that is where I spent my life. I come back to Mo again. I hope he found the armor and made a good life for himself and his son. I hope he made it to the blessedly Normal.

#The Web is filled with information on all of the names, images and titles listed in this paragraph.

*Hamlet, I, v

**Ronald Reagan’s usage

***Ted Nugent’s usage

I have kept political commentary out of this discussion for lots of reasons, but race is also inescapably political. I will limit myself to one opinion here: the ongoing effort by some state legislatures and governors to suppress the voting rights and opportunities of people of color is one of the most despicable and purely racist actions I have lived to see come back into political life. Those voting rights were bought with rivers of blood and pain in the fifties and sixties. Our democracy, already shackled by the contaminating influence of unrestrained money, cannot afford one more link in that chain.

You have a gift! Your writing style, your experiences, your passion/compassion, your words pull me into your world. I hope you plan to publish soon!