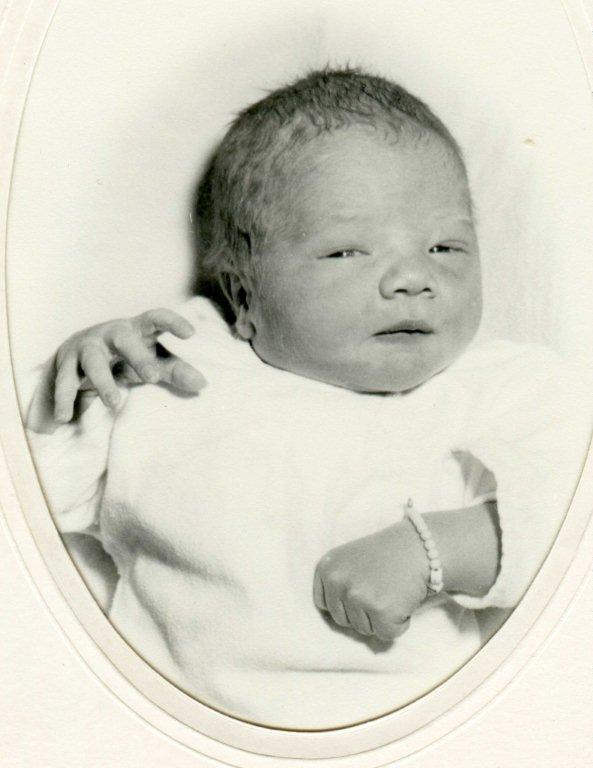

There are four of us. There should be six. Two brothers, the fourth and the sixth child in order, died as infants. We know so little about them that they do not even register as ghosts. Thomas, number four, survives in a photo, in his hospital wrist bracelet, in an album lined with 24 cards decorated in birds and babies, in strips of fragile newsprint, and in 59 white and cheerless sympathy cards. He perseveres in flash-shots of a few memories. Patrick appears in a birth certificate, in a brief obituary, in a line in a death registry, that’s all; he exists in a presence made only official; nothing remains of his body but one bare story.

In trying to reconstruct my mother and father’s lives, I’ve mentioned my brothers, but I have not directly thought about their absence. I have not spent time trying to see what might have been, who they might have become. Then, like a whisper spoken in another room, a breath of something on the air, their mysteries returned in the form of a small slip of white paper in my mother’s handwriting that fell from a file I was cleaning out. She had given it to me years before in response to my questions. It contained both boys’ birth dates and times. She had told me nothing else. My father never mentioned them. Their Catholic generation knew that the world really was a ‘vale of tears.’ What could be accomplished by talking about them? They kept quiet and went on. There were other children to feed and raise.

Of course, my mother had known them with her body and with all the maternal intuitions that accompany pregnancy and birth, but her memories have been swept away by infirmity. Even if she had reached the emotional point of strength where she might have spoken of them, she can no longer do so.

Thomas lived for 35 days. He was healthy and growing. Born at 7 lbs. and 13½ ozs., he had reached 8 lbs. and 6 ½ ozs. by June 2, 16 days before his death. At five weeks of age, he would have begun to hold his head up. My mother almost certainly saw his smile. His time spent crying was increasing. He would have grasped my mother’s fingers for the first time. He would have begun to recognize her voice. He would have become a fully recognizable, separate human being. Thirty five days is a long time for a mother to hold a child.

Thomas lived for 35 days. He was healthy and growing. Born at 7 lbs. and 13½ ozs., he had reached 8 lbs. and 6 ½ ozs. by June 2, 16 days before his death. At five weeks of age, he would have begun to hold his head up. My mother almost certainly saw his smile. His time spent crying was increasing. He would have grasped my mother’s fingers for the first time. He would have begun to recognize her voice. He would have become a fully recognizable, separate human being. Thirty five days is a long time for a mother to hold a child.

Then, in a catastrophe of a few days he was gone, rushed to Philadelphia by State Police escort, his death perhaps caused by an burst aneurysm on his heart (The Search #12: Post 93)

Of the two, I think my Mother was the one who carefully taped all the cards into Thomas’s album. Her handwriting is on his feeding record, also included. But I could be completely wrong. Maybe Auntie Glady, my mother’s sister who helped with all her babies, created the album. I don’t know.

If my Mother, why did she so carefully sort and store all those sympathy cards? Obedience to her maternal impulses to preserve something of her child? A record of condolences, each one maybe taking an atom of her sorrow onto others’ shoulders? Within the space of one page in the album, a reader wildly swings from reading “For the new fledgling/and the proud parents too/best of wishes, happiness/and a world of joy for you,” to sentiments that included “God knows best,” and you now have “a saint to pray for you.” One pair of creatures wrote this sentence alone: “Sorry for your loss but God needed him more.” My maternal aunts and grandmother vowed battalions of Masses, Rosaries, Holy Communions and Visits to the Blessed Sacrament. The contrast between the pages is so stark that it reinforces an authentic sense of tragedy regarding his death – new life, turn a page, death.

My brother can still see him in his mind’s eye playing in his bassinet. My sister pushed his baby carriage, sometimes dipping it so far back on its wheels that a neighbor ran across the yard, afraid that he would tumble onto the ground. On the terrible day of the race to Philadelphia, she recalls standing in the kitchen with our Aunt. The house was full of people.

Both attended the viewing. Annette remembers a tiny white coffin on a stand. As was the custom of the time, my father lifted her up and asked if she wanted to kiss her brother. She saw a white face surrounded by white satin and white bedclothes. Fred remembers standing next to my mother at the funeral home, looking at Thomas. She was crying uncontrollably. He asked if he could touch him. He still remembers that touch. Thomas would be 58.

Patrick went missing. He was never more than a name to us as children, and as adults, only a gravestone, an unseen death certificate and this: he never came home. I remember my mother in the dining room, in sunlight, and me asking where’s the baby. She was wearing a suit. I don’t remember her reply. There is no album, not one photograph, not one sympathy card. Patrick would be 53. He died after three days of life.

My sister thinks that my mother was in the hospital for a week. Dad alone went to the funeral. At some point in the last ten or twelve years, Annette asked about Patrick. Mom said that he had a hole in his spine and flippers where his arms and legs should have been (phocomelia). Later, she denied having said any such thing. It was her last pregnancy. She was almost 43 years old.

From 1950 to 1960 women in my mother’s demographic suffered 27 deaths per 1000 births, a 2.7% rate. Two of her four children born in this decade died.

We lived in Myerstown, Pennsylvania from 1949 to 1961. The Whitmoyer Laboratory facility was located within a mile of our home. Beginning in 1934 they manufactured veterinary pharmaceuticals and used arsenic compounds to do so. We played in the woods near the blue pools of sludge where they dumped their waste products. They had the hue of robin’s eggs. We waded in the stream in those woods. We drank well water.

Beginning in 1934 they manufactured veterinary pharmaceuticals and used arsenic compounds to do so. We played in the woods near the blue pools of sludge where they dumped their waste products. They had the hue of robin’s eggs. We waded in the stream in those woods. We drank well water.

The Myerstown home

The Myerstown home

Arsenic compounds have been linked both to spina bifida and phocomelia. In high enough concentrations, they can cause these massive birth defects. The EPA has designated the land as a Superfund Site, a piece of the earth so polluted that it required a special designation, a governmental warning akin to “Here be Dragons”. We drank water from a well. All of us. I cannot draw a direct line of cause and effect from water that had to have been laced with arsenic to Patrick’s birth defects, a condition my mother later denied, but circumstantially, I think one could build a case.

I don’t believe my mother’s denial. She said to me once regarding a medical issue of one of her surviving children, that she was the one responsible for the problem because she had given birth to this child. In her mind, her body linked itself absolutely to the bodies of her children (and to their moral and spiritual lives). Our afflictions were her fault. I think she might have seen Patrick as a culmination of her faults.

What an awful burden to shoulder.

If both had lived, space at home would have been tight – 4 brothers to a room, 2 sisters to a room? No, Patrick, terribly crippled, would have needed his own space. Many children born with spina bifida and phocomelia do not suffer intellectual disabilities. Patrick’s mind and sensibilities might have been normal. Knowing my mother, she would have been perfectly devoted to him, but she could not have looked after all of us on her own. The older children would have been pulled into helping care for the younger. Maybe Patrick would have taken off our adolescent edges and softened our self-absorption and angsts. Birth order suggests that the last born in large families is “the clown”, “the wild child”, the one who makes others laugh.* Maybe he would have been the brightest of all the lights at our family celebrations.

Dad almost certainly would have built another bathroom and one or two more bedrooms, one in the attic, maybe one in the cellar. He would have had to work other jobs after the State Police. We would have seen less of him. Auntie Glady, our second mother, would have become a near permanent presence.

The age division between the six children might have created natural allies and close connections of defense and loyalty, Annette with Fred, myself with Thomas, Rosemary and Patrick. Seen in this light, everything would have changed. Our lives would have branched out unknowably from the new dynamic. My brother and sisters and I lived our lives in their absence (but not in the psychological effects of their absence on our parents). Alive, what other sharp turns and shakings, joys, disappointments, sorrows, and amazements might we have witnessed? Their lives would have made our lives anew.

This essay is replete with maybe’s and perhaps’s, might have’s, may have’s, all the uncertainty that can be mined from a void, from an emptiness that caused my older sister Annette to weep when she thought of the lives Patrick and Thomas had missed. All I have done is rummage in a dark house, trying by touch to see what never was. Maybe all I’ve set down are 100 examples of make believe.

Annette often dreams of family. They visit her and speak — Aunts, Dad, Grandmothers, my mother too. When they appear, she knows she is dreaming. Fully aware, she talks to them. She has been asking my father to bring Thomas and Patrick with him when he calls. A day or so after I began questioning her about her memories of them, they came. My father stood at the foot of her bed, back straight, hands clasped at his waist , ‘at ease’, smiling. He said, “I brought them.” Then she saw Thomas and Patrick. Thomas was Dad’s size, about 5’10, and wore short, dark curly hair. Patrick, a strawberry blond, wore a huge scarf turned and arranged as a bow tie. Dad said that Patrick thought he was gay. Both of them kept their heads down. They never looked up. Dad said that both were very shy. As near as Annette could tell, they were in their early 20’s.

Annette often dreams of family. They visit her and speak — Aunts, Dad, Grandmothers, my mother too. When they appear, she knows she is dreaming. Fully aware, she talks to them. She has been asking my father to bring Thomas and Patrick with him when he calls. A day or so after I began questioning her about her memories of them, they came. My father stood at the foot of her bed, back straight, hands clasped at his waist , ‘at ease’, smiling. He said, “I brought them.” Then she saw Thomas and Patrick. Thomas was Dad’s size, about 5’10, and wore short, dark curly hair. Patrick, a strawberry blond, wore a huge scarf turned and arranged as a bow tie. Dad said that Patrick thought he was gay. Both of them kept their heads down. They never looked up. Dad said that both were very shy. As near as Annette could tell, they were in their early 20’s.

Thomas’s one day old photo shows him reaching toward the camera with his right hand, his fingers extended. He seems to have big hands, my father’s legacy. He reminds me of my brother. He looks more like a Wall than an O’Donnell. His image is unusually clear. When I held his hospital bracelet in my hand to photograph it, lightheaded, I had to brace myself against the wall for a moment. I miss the he that he might have become. I miss the brothers who never were.

*The Power of Birth Order by Jeffrey Kluger, Time Magazine, October 17, 2007

Mike,

I read this with tears in my eyes, thinking of my two sisters whom I miss dearly. I never had the chance to meet them, as neither left the hospital, I feel a sense of loss that is difficult to explain. Perhaps it is the small shards of pain I see in my father’s eyes as he smiles bravely, having lost two daughters and the love of his life unfairly, far too early. Thanks for helping me remember.

I had an older brother who lived two years, back in the 1950’s. Of the eight siblings remaining, seven of us never knew him. He comes up only occasionally in conversation, though I feel an occasional pang, of the enormous missed opportunity. Our lives have gone on and he is rarely even counted as a sibling when anyone asks about us. But at our last family gathering, our youngest sister Amanda, who has Down’s syndrome, raised a toast to him.

Mike,

How wonderful your words are about our brothers. I also often think how if they had lived how our families lives would have been.

We are such a close family and I know we would all have been the best of friends just as the four of us now are.

I try to picture how they would have looked,would they have gone to college,married,had children. What kind of work would they have chosen.

If only… two little words that we say over and over about Mom and Dad. If only we would have asked more questions about their childhood,courtship,jobs, our brothers……

Mike I read your blogs about our family so often. Of course always with tears. You have done such a wonderful job of discovering the lives of our parents.

I am so proud of you and proud to be your “little sister”. Mom and Dad would have loved every word of your writings and also be so proud.

I love you for what you have written.

Mr. Wall,

I’ve read many of your posts since you started the site but haven’t commented. Thank you for this essay; it is beautiful. I have always wanted to know more about my parents’ lives, but like many of us, they struggle to talk about the thoughts and experiences that truly weigh heavily upon them. Thank you again for sharing, as always.

Marybeth

Mike: Your writing brings into sharp relief brief memories of Thomas and Patrick. I find it difficult to recall more, as if the memories are ephemeral or fog-shrouded. Would it not be wonderful if we could reverse time’s arrow and have them here again?

What a wonderful tribute to our two brothers who I miss more and more as the years go by. The thought of all the great times we have had and will have in the future that they have missed makes me so sad. Tears still come to my eyes when I think of how much they are loved and missed–even after almost 60 years! I cherish the time I get to spend with you, Fred and Rosemary even more as we get older and every night in my prayers I say good night to Thomas and Patrick and tell them how much they are loved.